Curator

Revisiting Prohibition, Revisiting Universal Education, Meeting Heriberto Yépez

THE CASE FOR PROHIBITION

I’ve had a sense for a while that Prohibition is a sort of dark star in our politics - an event that, when it’s thought about at all, is regarded bemusedly and shudderingly, as quaint reactionarianism - but that it exerts its gravitational force over the War on Drugs, over perceptions of liberals, over deeply-embedded notions of the role that government should play in civic life. I’ve been thinking about this more concretely because, recently, I’ve been spending a lot of time around alcoholics - and the feeling that they have is of being rats caught in a trap, that, as desperately as they try to be sober, do their steps and go to their meetings, they are immersed in an alcoholic society and are fighting, basically, a hopeless battle. I remember one guy plaintively laying out his business plan for a ‘sober bar’ - a place you could go to in the evening, hang out and be social but without jeopardizing your recovery. To which my thought was that that’s a beautiful concept - and it’s amazing that we don’t already have that in the culture. And also - that there would be nothing to sell and the place would be about as fun as a Boys & Girls Club.

Mark Lawrence Schrad, a really smart writer for Aeon, lays all of this out in its historical context. The great myth, he claims, of how we remember Prohibition is that it was focused on restricting individual freedom. The reality was that its target from the beginning was ‘traffic’ and the coercive, predatory capitalism of the liquor business.

That’s an incredibly important distinction, and, thought about in that way, Prohibition turns out to be right on the fautline of two very different conceptions of civic freedom. The temperance movement assumed that the critical freedom was freedom to - i.e. the ability to construct a good life. Alcohol was - as had been recognized very early in the nation’s history - an impediment to that pursuit; and, ipso facto, a virtuous republic should curtail the availability of alcohol. The rivals to temperance - the scattered, inchoate opposition that eventually, with Prohibition’s repeal, became the common-sense plurality - advocated for freedom from, i.e. a sensibility that any incursion by the state on civil liberties, however well-meaning, is a type of bondage.

Those distinctions had been laid out in philosophical terms - the tradition of Locke as opposed to the tradition of Mill - but, with Prohibition and the twentieth century, they took on more grounded economic form. As Schrad writes, “Before the Second World War, so-called neoliberalism was a fringe economic doctrine….Its economists argued that any infringements of a citizen’s economic liberties – the right to buy, sell, and consume – were necessarily infringements upon their political liberties as well. As these doctrines moved into the mainstream….we’ve for the past 40 years lived in a world where political liberties and economic freedoms have blurred together.”

In other words, Prohibition was only secondarily about alcohol. What it really served as was the high-water mark of a Lockean, republican tradition in which government and civic virtue would co-exist harmoniously. Schrad quotes Frederick Douglass as saying that “all great reforms go together” - and Prohibition, ‘the noble experiment,’ was understood as belonging to the same category as abolitionism, women’s suffrage, unionism, an approach, in Lockean terms, of limiting ‘license’ for the pursuit of ‘true liberty.’ With Prohibition’s repeal and perceived failure, a key plank of liberalism vanishes - replaced by a rival tradition in which no distinction is made between ‘license’ and ‘liberty’ and capital is understood to have a truth and logic of its own. If people want liquor, runs the logic of the rival position, then the market has a certain obligation to sell it - regardless of whether or not liquor is bad for the consumers.

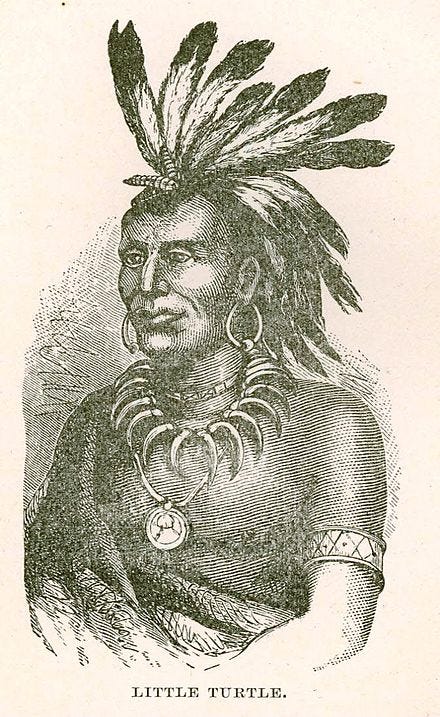

My sense is that these two strains of political philosophy represent the really critical fissure within American history. They are vividly discernible in the politics of the 1820s and ’30s - the Jacksonian Revolution - and in the dynamics surrounding Prohibition. The triumphs of the spirit of Jackson and, a century later, of neoliberalism have been so total that it becomes easy to forget that the opposing position had any sort of validity to it. But there were valid positions. The age following the Revolutionary War prided itself on a certain kind of restraint - particularly in a severe curtailing of Western settlement and (at least in contrast to later sensibilities) a surprisingly respectful attitude towards the sovereignty of First Nations. As Dresser notes, this spirit of restraint went hand-in-hand with temperance, and he digs up the story of Jefferson’s ban on liquor sales in ‘Indian Country’ - the result of a petition from the Miami chief Little Turtle against the ‘fatal poison.’ And 20th century Prohibitionism was infused with the same sort of restraint - the belief that government should intervene to curb predatory capitalism and to rein in society-wide addictions.

But there is of course a very powerful force within the American spirit that moves in a different direction - that insists on entrepreneurship, expansion, disinhibition. That spirit obliterated the careful restraints of the Revolutionary War generation in terms of Western settlement and obliterated too the very reasonable, judicious legislation of the Prohibition era. That spirit is very much with us in the concerted dismantling of unions and labor laws, in the opioid crisis (which is really the trafficking of narcotics from within the medical industry), and in the general assumption, of which Prohibition was so critical in fostering, that nothing, above all good intentions, can resist the pressures of the marketplace.

And I’m not really sure that there’s a good answer to that. Prohibition seems not really to have been enforceable - any more than Congressional safeguards at the beginning of the 19th century were going to stop Western settlement forever. But it is, as Schrad points out, at least worth acknowledging the idealism of the temperance movement - which wasn’t so much fusty or fundamentalist as it was progressive, believing that there was a better way to exist as a society, that government had some higher purpose than just bending with the caprices of the marketplace.

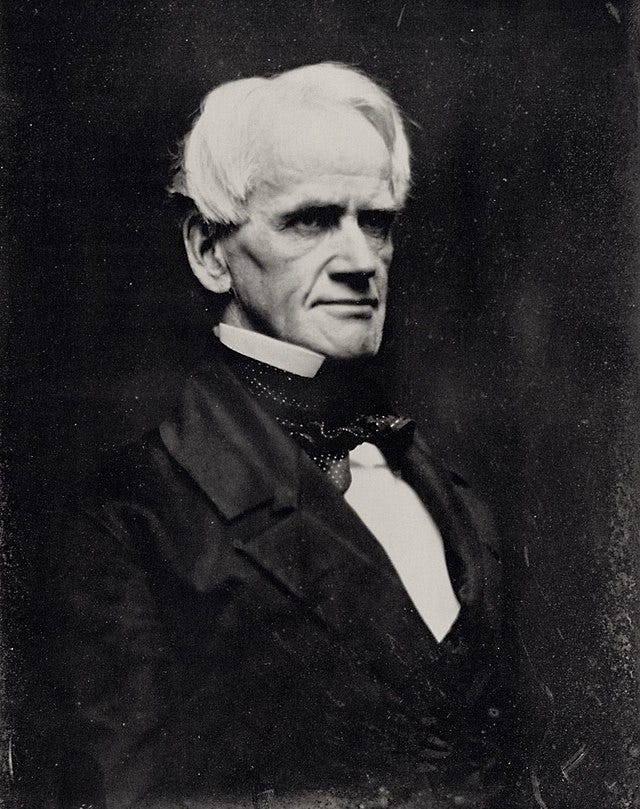

GOODBYE TO UNIVERSAL EDUCATION

One of the great luxuries of not having children is not having to think about school curriculums - and it’s been a pleasure in my life to skim past all the overheated debates about Critical Race Theory and the 1619 Project, as well as those about remote learning and school closures and the general collapse of the education system. But I seem to be in a sort of 19th century mood this week and was struck at coming across two different pieces that discuss Horace Mann, the public education pioneer - a sign that intellectuals are really trying to understand the foundational principles of public education and to use them as a path out of the mess we’re currently in.

Writing in The New York Times, Anya Kamenetz makes an impassioned plea for a renewal of Mann’s universalist vision. Her adversary is, not so surprisingly, the ‘parents’ choice’ wing of the right with its secessionist tendencies against the public school system. Writing in The Point, Jeffrey Aaron Snyder tries to carve out a middle ground modeled on Mann’s careful neutrality - a distinction between ‘education’ and ‘indoctrination’ with schools remaining “scrupulously non-partisan and non-sectarian.”

I’m sympathetic to both Kamenetz and Snyder. The sort of secessionism practiced by Christopher Rufo and the parents’ choice movement is clearly problematic for the whole civic order, and, meanwhile, Critical Race Theory or its high school derivative, which Snyder calls ‘Antiracism, Inc,’ are pretty obviously cases of indoctrination. The short-term solution probably is something along the lines of what Kamenetz and Snyder are suggesting, a return to first principles, an insistence on both universalism and strict non-sectarianism - the old values returning as a way to bolster a tottering education system.

But thinking more intellectually, and less from the vantage-point of public policy, I can’t help but wonder if it isn’t time to quietly drop Mann’s model and shift towards an understanding of education that’s a bit more suited to the circumstances we find ourselves in. The date of Mann’s reforms is important - the 1840s, the period of Manifest Destiny and of outwardly radiating, propulsive energy. As Sugata Mitra kind of crudely put it in a Ted Talk, nations at that time didn’t have computers, so they created a “computer made up of people - the bureaucratic administrative machine - and then made a second machine to produce those people: the school.”

Mitra’s point is that the education system we have with us - the holdover from Mann’s time - isn’t so much broken as obsolete, "producing [workers] for a machine that no longer exists.” Mitra treats the purpose of education as fundamentally imperialist. The more anodyne way to put it is that it’s nation-building - people like Mann and the reformers who followed him working to develop a core set of skills and shared educational language and scrupulously pushing out any divisive elements.

That universalized education system was the great glory of America for a long time. As Kamenetz writes, the approach pioneered by Mann is “more or less how America became the nation we recognize today.” But there are at least three major, foundational flaws with it: 1.The system is conservative and classically-rooted and assumes a more or less steady, unchanging body of knowledge, which tends to put even the best-educated students at a marketplace disadvantage compared to the autodidacts who are assiduously learning the most recent breakthrough technologies (that was mechanical and electrical engineers in the early part of the 20th century and and is now computer programmers). 2.The system does not sufficiently account for differences in aptitude and interest and tends to assume a parity between different disciplines - with the result that students who show a talent early on in one field waste critical formative time studying material that will be of no use to them. 3.The system encourages a uniformity of thought and experience that results ultimately in a bland and conformist workforce. (Mitra writes somewhat meanly that the system is dedicated to “producing identical people.”) To which could also be added that the system is so assiduously milquetoast and non-confrontational - Snyder is convincing in tracing much of this tendency to Mann’s own mild Unitarianism - that the humanities curriculum ends up just being very staid and boring with none of the fire that its subjects truly warrant.

The merits of the system have been obvious enough and are of course worth celebrating - the creation of a vast white-collar class; the development of national pride and solidarity; and a certain bureaucratic smoothing-out of society-as-a-whole, with inbuilt pathways to meritocratic advancement. But we’re maybe past due to acknowledge that the flaws have caught up to the successes. The path out isn’t so much a vast overhaul as quiet differentiation, which has already been happening - the expansion of magnet schools; a greater willingness to see vocational and technical schools as offering a perfectly viable, perfectly employable alternative to the classical liberal arts; and greater opportunities for early specialization for high-achieving students (AP classes and IB programs, for instance). A wonderful complement to that - and which seems inevitable in the Zoom era, although it hasn’t happened yet - would be a more serious approach to adult and continuing education, a sense that education is a lifelong endeavor for those who wish to pursue it as opposed to a mandated regimen that, for most people, ends abruptly the day they turn 22.

I haven’t really formed an opinion on Biden’s student loan forgiveness, but the best way to think about it may be as a kind of apology from the government for the shortcomings of the universalized education model. It just hasn’t really worked is the simple reality. A standard white-collar worker isn’t earning enough to pay back the rising cost of education. The alternative (not at all hard to envision) is something a bit closer to the European model - students tracking earlier in their academic careers, thinking more seriously and critically about where their aptitudes and their earning potential lie; and high-achieving and neurodivergent students given more latitude in pursuing their particular passions.

The education of sameness - what Snyder calls Mann’s “lowest common denominator” approach - served its purpose for nation-building, but the nation-building phase is passed. In terms of national destiny, we seem to be heading towards something that’s a bit more federalized, the egalitarian, purely democratic vision replaced by a more pragmatic respect for difference and with the understanding that people’s life paths take them on very different trajectories. The education system will sooner or later have to adapt with that - more differentiated and more attuned to the talents and affinities of individual students.

HERIBERTO YEPEZ - TERRORIST

I don’t have much to add to this tribute to Heriberto Yépez - I haven’t read Yépez - but this kind of piece is basically the highest form of literary criticism, the introduction of a writer whom the critic adores and is capable of explicating.

Yépez is a familiar type - the enfant terrible, writing quickly and caustically, interested, above all, in exposing the intellectual and moral ‘corruption’ of other writers. Everybody in the Mexican literary world seems to have tired eventually of the shtick - he was fired from a prestigious post as Milenio’s columnist and his more recent work appears, as Nicólas Medina Mora writes in the n+1 piece, in “publishing houses so marginal that the term small press proves inadequate” - and Mora gets credit, again, for sticking with Yépez, for claiming that the splenetic persona wasn’t just performance art but was, in a sense, the only valid position for a contemporary Mexican writer, refusing to accept the basic premises of American imperialism and of the bourgeois Mexican literary scene that caters to it.

There’s a great deal in Yépez that I find congenial. To just list qualities, these are:

-A belief that a writer should be prolific - that writers exist to write, not to publish or to cultivate their reputations;

-A belief that literature is essentially a way of life, as opposed to the creation of products, no matter the level of excellence of the product;

-A belief that literature should be incendiary and should be animated, above all, by courage;

-A belief that the underlying purpose of a work of art is the artist’s self-transformation. This is not exactly a process of maturity but more of a shattering of the self into disparate personae, an exploration of just how infinite the self really is. As Mora writes, “Contrary to what we’ve been told we need not remain identical to ourselves.” This is a very subtle and poorly-understood dimension of art, and Yépez seems not only to have inhabited it fully but to be livid with anyone else who has not done so. Mora writes, “Yépez thinks of literature not as an aesthetic game beyond the realm of morality, but as an edifying practice…Part of his frustration with other writers seems to stem from the fact that so few of them are willing to avail themselves of their capacity for reinvention, preferring instead to persevere in their corrupt ways.”

I have no idea whether I would actually like Yépez’s writing or not. I was a little less than impressed with some of the poetry Mora excerpted for his article - particularly the ‘extraordinary poem’ that, twenty times, repeats a variation of the phrase “Americans rule the world” - but, actually, that’s not really the point. My current conviction is that art, basically, is courage - that’s what we respond to from a work of art, especially if we don’t quite know why we’re responding to it. We respect people who take risks and, as an audience, we care much more about that than whether or not they are successful in their risk-taking. But for artists who are courageous, as Yépez clearly is, there are specific and tremendous pitfalls. Courage is, of course, almost perfectly indistinguishable from stupidity; and there is a tendency, which may well have beset Yépez, of relying on provocativeness as a trick and crutch. The sense, though, is that something exciting is happening here - both in Yépez’s work and in n+1’s willingness to turn over so many column inches to Mora. The really important point, actually, is the sense of moral conviction - that the school represented by Yépez is not about ‘art for art’s sake,’ that it is driven by an ethical sensibility at the same time that there’s an understanding that art (i.e. the brave and honest exploration of the soul) is the highest ethical imperative of all.

So important to consider that there might be other values besides personal liberty that could guide us, essentially social beings. Liberty may be an easy default, since it is so difficult to achieve mutually beneficial community. Unfortunately, I think that the motivation of at least some Prohibitionists was to preserve (white) civil society against the onslaught of those immigrants from Ireland and Italy, who brought with them their cultures of whisky and wine. Following another thread here, I recall a stat that the top 20% of drinkers (those consuming more than 2 drinks a day) account for 80% of alcohol consumed (and the 10% of drinkers who have 4 or more drinks a day account for 50%) . Thus, most of the profits from the liquor business are extracted from problem drinkers, and the incentive for marketing and advertising is to create as much addiction as possible. Look for the money.

Raising an O'Doul's high to the case for prohibition