Dear Friends,

I’m sharing the ‘Curator’ posts for the week. These are riffs on the ‘artistic/intellectual web’ - all posts on history this week. As ever, discussions and arguments welcome!

-Sam

A DIFFERENT VIEW OF NATIVE AMERICAN HISTORY

The maximally umlauted Pekka Hämäläinen has a book out arguing for a radically different view of Native Americans and the colonization of America. Without dealing with the merits of his Indigenous Continent (which is on the reading list), I wanted to deal with how it reshapes cultural dialogue around this topic - particularly through David Treuer’s impassioned review in The New Yorker.

For Treuer, who is Ojibwe, this is the book he’s been waiting for - instead of casting everything in Native American history as a story of victimization, the narrative becomes about struggle and complex historical dynamics within which 1492 is just one date among very many. As Treuer writes movingly, discussing his formative reading of Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee, “I can only wish when I was that lonely college junior and was finishing Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee, I’d had Hämäläinen’s book at hand. It would have helped me see that there was indeed a larger story: that my civilization hadn’t been destroyed; that my tribe’s contribution to the past wasn’t merely to fade away into history.”

Come to think of it, I’m amazed that this conversation hasn’t been happening more aggressively in public space before now. It’s obvious enough that the story of colonial brutality and native victimization - which has become the default, sacrosanct mode of thinking about American history - is a remarkably on-the-nose recapitulation of the old myth of ‘the noble savage.’ Native Americans are understood to have, in effect, no agency - they become eternally righteous but at the same time eternally innocent, with no narrative role to play except as victims. What’s worse, that narrative, as Treuer notes, assumes that the story is played out: Native Americans lost, ‘whites’ won, and, in return for their victory, whites have to spend some indeterminate period of time expiating their guilt. As storylines go, that one has the virtue of simplicity, but it completely overlooks the fact that Native Americans weren’t annihilated; that there are millions of Native Americans alive today; that the story is ongoing.

As Treuer writes, the first move is to get out of the ‘noble savage’ trap altogether - this means, above all, dropping the myth of eternal innocence. “My ancestors didn’t live in harmony, they lived in history,” writes Treuer. This is not at all to detract from the beauty of Native American society pre-colonization, but there’s the important distinction of seeing that society not as some sort of primordial paradise but as civilization, hard, concerted work and subject to the vagaries of politics like everything else. Suddenly, viewed from this vantage-point, the whole story starts to become much richer and more interesting. Native Americans aren’t reduced to some homogenous mass - the term ‘Native American,’ like all of its predecessors, starts to seem woefully inadequate - but are recast as a bewilderingly diverse array of peoples, engaged in ever-shifting political alliances and conflicts with one another. And, from this vantage-point, there’s a place for pride in the Native American story: it wasn’t one-sided victimization, it was an ongoing battle for hundreds of years in which Native Americans gave as good as they got and often did so facing staggering disadvantages in manpower and weaponry. As Treuer writes with (I think) fully justified pride, “Tribal nations, including my own, were shoving Europeans around (and eating their hearts) for quite a long time.”

I do of course know why it’s been difficult to make these points. The narrative of victimization has been so strong in American politics that it’s become heretical to think in any terms other than that of native innocence and white guilt - and the obvious fear surrounding a narrative like Hämäläinen’s is that it comes across as even-handed, assigns culpability for violence to both sides. But, in terms of reaching a new cultural consensus, the great merit of Indigenous Continent is that it actually doesn’t let whites off the hook at all. If anything, the really brutal settlement of the 19th century (Jackson’s conquests, Wounded Knee, etc) comes to seem even worse. It wasn’t just some sort of protoplasmic-like expansion - the eternally guilty whites carrying out their perfidious destiny, migrating ever-westwards. It was a conscious attempt to override an uneasy-but-not-altogether-unharmonious interplay between settlers and Native Americans that had developed over several hundred years - a series of treaties and trading arrangements that were (more than is usually remembered) respected by European powers and by the early U.S. government before a mid-19th century paradigm shift obliterated those careful balances. As Hämäläinen puts it, “The familiar narrative only works if you skip over a few centuries.”

For a ‘white,’ like myself, there is still very much the need for guilt and expiation - and the guilt hits closer to home. It doesn’t land so much on the ‘original sin’ of settlement - it’s hard to be too angry at people who crossed an ocean having no idea where they were going - but it does land on Manifest Destiny, the ‘conquest of the West,’ the surge of 19th century immigration and an accompanying vision of cheap land in the West, a particularly toxic combination of technological determinism and suprematist ideology. In a less-trenchant review of Indigenous Continent for Harper’s, Daniel Immerwahr asks, “Indigenous Continent raises a pressing question: how best to tell the story of oppressed peoples? By chronicling the hardships they’ve faced? Or by highlighting their triumphs over adversity?” The real answer is of course to tell the story the way it happened, with complexity and moral ambivalence, but I do get Immerwahr’s point. ‘History,’ in the space of political consumption, is largely a matter of constructing narratives that we can agree on - and Hämäläinen strikes me as being both in line with what happened and with political palatability. We move from an ahistorical binary in which Europeans were ‘white supremacists’ and ‘genociders’ from the very beginning while Native Americans lived in permanent primeval paradise; and we find ourselves in actual history, in which peoples are disparate collections of interests as opposed to some sort of racially homogenous bloc, in which populations move, in which violence is a two-way street, but, at the same time, we acknowledge and atone for the horrors carried out by the colonists and above all by the United States in the Industrial Age, while Native Americans are able to regard their past with pride - for, as Treuer points out, “eating the hearts [of Europeans] for quite a long time,” but, more than that, for constructing and continuing to construct a rich, complicated civilization.

‘THE JEWISH QUESTION’ - AGAIN

In the previous riff, I called myself ‘white,’ although I guess have to qualify that by pointing out that I’m half-Jewish and then this gets into the thorny question of whether ‘Jews are white.’ This question comes up in a discussion thread on Glenn Loury 's Substack - Loury, who has a wonderful ability to steer fearlessly in the direction of all possible difficult topics, had said something off-hand linking Jews with other Europeans, and a Brown University colleague of his wrote in to query, a bit disjointedly, whether Jews are actually ‘white.’ What strikes me, above all, is that this is still a debate we’re having and still as fraught as it was a couple of hundred years ago. Back then - the debate was centered largely in Germany - it was the ever-vexing ‘Jewish Question,’ the idea that nationalist self-determination seemed to be an absolute unequivocal good but which then presented the impossible conundrum of what to do with an ethnic group that was distinct in itself but was not grouped along the accepted lines of a nation (the difficult point being, above all, that Jews tended to live as a minority population amongst other nationalities as opposed to being a majority within a geographically-circumscribed region). As it turned out, ‘The Jewish Question’ was really The German Question - the problem being that ethnically-pure nation states weren’t quite the unalloyed good that 19th century volkisch-minded nationalists assumed they would be; and the challenge of nationalism, for all modern nations, ended up being how to construct a somewhat federalistic state with protections for ethnic minorities.

In the 21st century, the ‘Jewish Question’ seems to be surfacing in another form. Our culture - very unfortunately, I would say - has defaulted to a racially-deterministic understanding of identity. In the last years specifically, the old narratives of assimilation, the ‘melting pot,’ and, finally, of ‘multiculturalism’ have given way to a brutal binary of ‘white’ and ‘of color.’ These are supposed to divide up evenly along the matrix of power. ‘White’ means wealthy, privileged, connected. ‘Of color’ means oppressed. And white, in this context, is understood also to mean guilty - intrinsically racist and intrinsically ‘white supremacist’ (a term that ten years ago applied to, like, David Duke but now seems to apply to everyone with light skin).

I am so horrified on so many levels that this is where our culture, and our dialogue on race, has gotten to. There’s so much to be said about it - why we’ve brushed past so many other ways of dealing with a person’s identity to focus exclusively on skin; why we’ve allowed ourselves to ignore the panoply of ethnic diversity and to zero in on a binary; why we’ve given up on any narratives of improvement in race relations (call it the John Lewis model) and seem to have decided that racial differences are ineluctable and linked to hard-and-fast socioeconomic axes (call it the Ibram X. Kendi model). But, for this riff, I wanted specifically to talk about Jews - and to raise the possibility that just as the ‘Jewish Question’ in the 19th century pointed towards a critique of nationalism for those who were astute enough to notice it, so the contemporary iteration of the Jewish Question exposes the follies of thinking about everything in terms of race.

‘Are Jews white?’ is the question. The answer is: well, sort of. Jewishness is an ethnic designation that’s linked to Europe but really linked to a Middle Eastern Semitic lineage. But, as in the age-old parlor game, Jewishness isn’t exactly ethnic, it’s also religious, and, for instance, the Lemba and the Ethiopian Jews are fully Jewish no matter that they are not European or Middle Eastern. So, the real response to asking ‘Are Jews white?’ is that it’s a stupid question: some Jews are white, some Jews are not white, many Jews are mixed, etc. But the question ‘are Jews white?’ isn’t really a question about skin color, it’s a question about power. The question is: ‘are Jews powerful’ or ‘are Jews oppressed’? And this is, if possible, an even more stupid question. The answer, of course, is that, like everybody else, some Jews are sometimes powerful and sometimes oppressed. Some of the Jews who were exterminated during the Holocaust were powerful up until the time when they had their assets seized and their travel restricted (and many more who were exterminated had never had any power at all).

But I can tell that the question about whether Jews are powerful or oppressed is sort of screwing everybody up. In the United States, Jews have high median wealth, high median education levels, and tend to have lighter skin - therefore, as runs the logic of our era, Jews must be powerful. But for contemporary anti-Semites, it becomes baffling that Jews should also count as oppressed - hence the endless fixation of attempting to disprove the Holocaust.

While the latest round of anti-Semites work to wrap their mind around this puzzle - how can members of the same ethnic group at some times have power and at other times be oppressed by power - there seems to be a lesson that the rest of us can draw from this whole discourse i.e. that the attempt to align the axes of power with fixed rubrics of race (as prescribed most peer-reviewedly by Critical Race Theory) is hopelessly reductive. What the ‘Jewish Question’ really showed - in 19th century Europe as now - is that it’s possible for people to have multiple identities at the same time. This should be screamingly obvious in an era in which so much of the society has gotten past the racial theories and ethnic homogenization of the 19th century, now that ‘mixed marriages’ and ‘inter-racial dating’ are so common that it makes me feel quaint even to write out those terms. But, as it happens, this is not as obvious as it might be. And at a moment when the society is becoming so heterogeneous and diverse as to be truly dizzying, our ability to talk about ethnicity has somehow reduced to ‘white’ or ‘of color’ - and with everybody of any more diversity summarily assigned to one category or the other. The hope I’d have from the current round of public anti-semitism - Ye; Kyrie Irving, etc - is that we do think about ‘the Jewish Question’ and draw the right conclusion from it, that our contemporary way of thinking about race (find your place on the axis of skin color and power) is just as reductive and ridiculous as was 19th century super-nationalism, that identity is, for everyone, a composite.

WHAT WAS ROMANTICISM?

The Curator section this week seem to all be about inveighing against the 19th century. The point is that the 19th century was a particularly acute sort of pressure-cooker - trends set in motion centuries earlier by Baconian technocracy came suddenly to a head and the West found itself moving propulsively forward into a new sort of existence, industrial, deracinated, and with technology understood to be a good unto itself. It’s understandable enough, in some sense, that on this first pass at ultra-modernity the 19th century got so much so wrong. Its particularly toxic legacies that I’m thinking about at the moment are super-nationalism (i.e. a doctrine of racially homogenous majority rule); a turbo-charged imperialism (e.g. Manifest Destiny, the Scramble for Africa, a new type of colonialism that did away with the bilateralism of an earlier era and emphasized the intrinsic right of the more powerful to dominate); a cruel Social Darwinism that was startlingly endemic among elites in the latter half of the century; a tendency towards totalizing thought that pitched the solutions for modernity in ideological terms (e.g. Hegelianism or Marxism). And Romanticism comes in for a similar censure .

There’s a new book out by Andrea Wulf, Magnificent Rebels, that usefully frames the Romantic movement - rendering it as, in several vital ideas, the production of a very small group of people, who all knew each other, were all talking to (and sleeping with) one another, all centered on the small university town of Jena, at the time in the German province of Saxe-Weimar. As Adam Kirsch aptly writes in a review for The New Republic, “Jena at its peak might have boasted a higher concentration of genius than Renaissance Florence or ancient Athens.”

I’d never realized this - that all of the famous figures of the German Enlightenment knew each other; and that they were so intertwined. Goethe and Schiller were best friends. Fichte and Schelling were given posts in Jena on Goethe’s recommendation “simply,” as Kirsch writes, “so that Goethe would have interesting people nearby to talk to.” And, when it gets to sex, it really gets interesting - Caroline Michaelis having her open marriage with August Schlegel, which was ruined by her love affair with Friedrich Schelling, which was largely ruined by the jealousy of August Schlegel’s brother Friedrich, who was also in love with Caroline, but dealing, at the same time, with a tumultuous love affair of his own with the disinherited daughter of Moses Mendelssohn. So great fun all around! - and, as Kirsch writes, these interpersonal dynamics are “the real subject” of Wulf’s book, which is basically a pastoral and a celebration of Romanticism in its nascence.

But there is a dark side to all of this - and I really was fascinated to discover the linkages between all these figures who have been such bogeyman of my intellectual imagination. Hegel I blame for the next century-and-a-half of totalizing thinking - the idea that history itself had a direction (and which provided an alibi for technocratic materialism as well as for any number of conniving ideologues). Fichte I blame for the ‘volkisch’ turn in German nationalism, which would have such lamentable consequences in the 20th century, and is still very much with us in, for instance, the messianic, acquisitive nationalism of Putin’s Russia.

Romanticism is one of these impossible-to-define terms - everybody seems always to mean something different by it. In an aesthetic dimension I very much like Romanticism, which I tend to think of as a useful corrective to the runaway rationalism of the Enlightenment. But, as Wulf and Kirsch observe, there is a side to Romanticism that’s very different, that’s about progress just as much as the Enlightenment but about progress with a wider lens, that takes in what we might call ‘abnormal psychology.’ This is a bit closer to what the spirit of Jena was about - and Kirsch makes the compelling case that, when we talk about ‘Romanticism,’ that really may be what we should have in mind. “If there’s a single point where all these lines of meaning converge,” writes Kirsch, referring to the various definitions of Romanticism, “the best candidate may be the book On Germany, published in 1813 by the French intellectual Germaine de Staël” - which was the book that popularized the ideas of Jena internationally.

What I find so enthralling about these intellectual clusters is the idea that movements that played out over centuries and vast populations can - sometimes - be discerned in microscopic form in the debates between close acquaintances who had no idea that they would go on to become so influential; and that it actually can be possible to referee on who was right and who was wrong. I’ve written a piece recently that touches, a little obliquely, on a similar pattern in Elizabethan England - and on the discomfort of that era with Francis Bacon’s incipient technocratic materialism. A similar sense of cosmic ideas in the balance is felt in Plato’s Apology and in some of the more famous texts of Classical Athens. And same goes for Jena in the Romantic era - somebody like Goethe seemed to have a very acute awareness of where materialism was headed and attempted to head it off, to restore an older, more humanistic dispensation. His near-neighbors, though, Fichte and Hegel, were thinking in a very different direction - towards dialectics and the ‘march of history,’ the ‘Reason’ of the Enlightenment but charmingly coupled, now, with the abnormal, the demonic, and all the pet goblins of Romanticism. From Jena it’s a short jump to Bayreuth.

The charm of these sorts of histories - more than the love affairs, the really good gossip - is this sense of the ongoing, eternal debates, the sense that what Goethe and Fichte and all the many Schellings and all the even more Schlegels were arguing about still very much matters and has real stakes to it; modern history might have looked very different if, say, Goethe had pressed his points just a little bit harder, if some of the Jena crew had reached different conclusions than they did.

CAN CASANOVA BE SAVED?

If all the other riffs this week have been about the 19th century, this last one deals with the 18th. There’s been a kind of ongoing consensus that the real ‘meaning’ of Casanova - as distinct from the use of his name as a stand-in for libertinism - is the value of his writing in illuminating the true inner life of the 18th century. “His History of My Life is the most valuable record of the 18th century,” writes Zweig. “Not even the plays of Goldoni give us a picture of 18th century Venice half as vivid as that of Casanova. His eye for detail is as unerring as his ear for dialogue, and since he mixed in all classes of society he knows how to bring them all from senators to gondoliers and laundresses to life,” writes John Julius Norwich. “His account amounted to a kind of alternative Enlightenment encyclopedia,” writes Clare Bucknell in a dismissive treatment of Casanova in Harper’s.

But Casanova, of course, does not stand up well to the mores of the 2020s. Leo Damrosch seems to have written a book on “the challenge of Casanova” above all so as to bring him into the docket and assess his morality according to the standards of MeToo. And if Damrosch is prosecutorial - as Bucknell writes in her review, “Casanova’s claims about mutual pleasure are queried; the voices of women he seduced are listened to; instances of sexual violence, assault, rape, gang rape, are frankly called out” - Bucknell delivers a verdict that goes beyond sexual misconduct and indicts just about every possible quality of Casanova’s. He is assailed for being a travel writer who is insufficiently interested in travel (of a trip to Moscow, he had written “Within a week I had seen everything”), for his sometimes reactionary political views, for his criminal record, for the ‘conjuring’ that made up a major part of his income, for his lack of discipline in writing early in his life, for the logorrhea of his writing when we finally got down to it (“words never failed him flooding out as copiously as, in previous decades, sperm and sweat had done”), for some inflation in his sexual record-keeping (his claim to having ‘invariably’ induced multiple orgasms is particularly scrutinized), and for some other patches of self-aggrandizement. As Bucknell writes, “What the story of his exploits does offer, though, perhaps despite itself, is one of the fullest records of the century’s strategies for representing itself: the organizing fictions and tropes it leaned on; the arguments it employed to understand and justify its darkest impulses; the lies it periodically needed to tell.”

What’s in balance here, of course, is the question of whether Casanova is rehabilitatable, and Bucknell’s very faint praise indicates that he is - by the slenderest of margins and for the magnanimous, not-exactly-flattering reason that his deceit can illuminate the deceit of his century (a bit like a serial killer being kept alive so that others can study the psychology of serial killers).

All of this strikes me, not so surprisingly, as a very wrong-headed way to approach both history and literature - assessing Casanova’s work through a judgment of Casanova’s moral qualities. But the value of Casanova is, entirely, that his writing is in an amoral realm - he is documenting his era, recording its sex life, its conversation (far more than its reputation might indicate, a great deal of the History of My Life is conversation; philosophy; political chatter), its little quirks. He was able to do that - the work of a diarist, essentially - because he didn’t seem to care all that much what others thought of him (or at least didn’t care if he was judged according to conventional morality). Bucknell witheringly quotes a line of Casanova’s from The History - “I would perhaps have omitted [the detail] in talking to a lady but the public is not a lady” - as a demonstration of the condescension and misogyny that was endemic to him, but, the unfortunate phrasing aside, there is real value in the point that Casanova is making, that others might defer to niceties and be better people, but he has chosen to prioritize truth-telling. As George Smiley puts it, discussing the recruitment of spies, “Such odd circumstances do seem to provide us with suitable personnel” - and a good memoirist is basically the same thing as a good spy. One doesn’t look for moral qualities in a spy. Evaluate memoirists by their moral qualities and you end up with very tame, very non-revealing memoirs.

As Bucknell writes, our understanding of history has gotten to the point where we are capable of dealing with the past solely through our particular moral prism - Damrosch’s biography of Casanova is permissible only because he “reads against the grain weighing the lure of the legend against a 21st century assessment of its costs and harms.” But this is asking all the wrong questions. Casanova has nothing to do with the mores of the 21st century; his value is that he illuminates, vividly and honestly enough, an era that thought about things very differently than we do.

Love how you brought this full circle at the end. I'll put a James Baldwin quote down below from his "Notes of a Native Son," essay, which very much colors a lot of the "identity philosophy" he engages with from then onwards. It seems to me we're experiencing the logical result of digital avatar-ification of the Self, and the resulting narcissism that comes with the politics of extreme individualism. Much of what we're' marketed these days is to pigeonhole much of our own personal sense of identity into smaller and smaller categories in the name of expansiveness. It's a tough sell. I've been thinking--and probably more importantly, *feeling*--a lot about the moralism of identity, and I keep thinking about the James Baldwin quote down below. There's something there. Thanks for your essay.

“It was necessary to hold on to the things that mattered. The dead man mattered, the new life mattered; blackness and whiteness did not matter; to believe that they did was to acquiesece in one’s own destruction. Hatred, which could destroy so much, never failed to destroy the man who hated and this was an immutable law.” Notes of a Native Son

Oh I think I read Chas Fort as a kid. (Wow that’s a deep cut. I don’t think I’ve thought him since adolescence. Anyway I’ll have to check it again on the strength of your recommendation. )

Yes, the origins of modern anxiety “was I supposed to be at Deux Maggots this WHOLE TIME...dammit!”

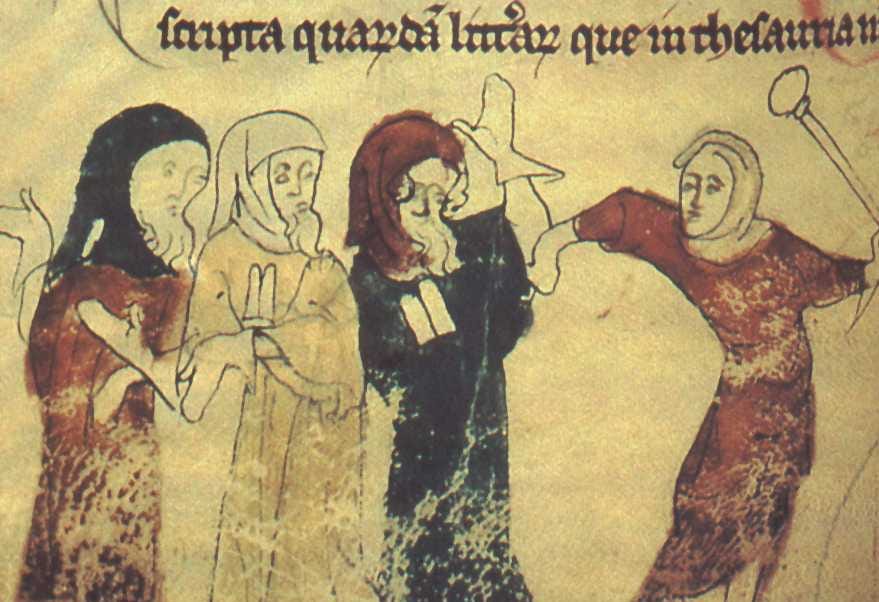

Alas, according to feminist history there were an awful lot of women in convents and private parlors having extremely interesting thoughts in the prior 500 years or so, generally lost to God and other silences.

I’m currently reading Fuller’s memoirs. It seems we are often in the same patch