A PATH OUT OF GREED?

A lovely piece by Gregory Claeys in Lapham’s Quarterly about the perceived rise of luxury in the 18th century. This would all seem to be the height of obscurity - the texts relied on, Memoirs Concerning The Life And Manners of Captain Mackheath, Memoirs of the Court of Lilliput, and so on, are likely not have been checked out of the library for a very long time before Claeys got ahold of them - but they are relevant. The belief is that greed is not intrinsically part of human nature, as Milton Friedman and Gordon Gekko would have us believe, that greed is culturally-determined and that various historical periods feature a heightened degree of greed as a result of circumstances and of a sort of mass mania.

We have been in the hothouse of greed for so long - have accepted more or less uncritically the position of Adam Smith (the avowed adversary of Claeys’ 18th century utopian texts) - that it’s become difficult even to imagine any other dispensation. And so for me, texts like Claeys’ and their American counterparts from around the Era of Good Feelings are very edifying and encouraging - the sense that there was a distinct paradigmatic shift in the Enlightenment towards runaway capitalism, that the more agrarian, communal models got blown away in the particular circumstances of 18th century globalization and of the Industrial Revolution, but that that ethic is circumstance-contingent and doesn’t necessarily have to win.

As The Memoirs Concerning The Life and Manners of Captain Mackheath movingly put it, “There arose among us a general and uncommon desire of money, and after this an extraordinary appetite for power; the two great fundamentals of every evil. Avarice immediately overthrew all probity, and trust, and mutual confidence;…After this extraordinary change of property, virtue seemed to become vice, and vice, virtue; and all men inclined to think that if they had wealth, they had a right to everything.”

A depressing formulation - but the real point is that ‘Captain Mackheath’ can remember some other way of being and is determined to see the luxury society, the advent of runaway globalized capitalism, as ultimately a trend, even if a particularly pernicious one, which can be reversed through some concerted effort of will.

Claeys itemizes four different ‘models of virtuous restraint’ that, in the 18th century, served as counter-narratives to the obvious rise of capitalism and the ethic of greed and luxury. These were 1.the arcadian ‘primitivist’ state of nature; 2.the ascetic Christian community; 3.the classical republican ideal of circumscribed commerce; 4.a kind of monarchist reaction to liberal laissez faire.

There are conceptual problems with all of these - namely, that they are all predicated upon a dislike of trade and an urge to isolate; and trade, I am convinced, is just a natural human trait, an extension of innate curiosity. But, nonetheless, I am very sympathetic to the project of these 18th century atavists, as revived by Claeys - their desperate attempt to hold back the tide or at least to send a message to future generations that, if there ever comes a moment when it’s possible to hold back the tide, that it’s a wise idea to do so.

My guide in thinking about this period has been Hilaire Belloc - the great bellicose belletrist of the Edwardian era. Belloc’s theory is that political science and economics tend to turn on the mode of governance - whether capitalist, socialist, etc - but these systems are essentially just gradations of one another. The real division is between centralization (i.e. totalization) and distribution. ‘Distribution’ sounds a bit fusty - it has Paleoconservative connotations and Belloc intended it in a very fusty way, arguing for the economic system of the High Middle Ages as opposed to the predations of the alleged Renaissance - but it’s also possible to describe it more gently as advocacy for ‘mixed systems.’ This is an aspect of political philosophy that I find to be badly underestimated. We tend to talk about, for instance, the United States as being capitalistic, but, with 15% of all jobs government jobs and with 20% of Americans using some form of welfare and 20% on social security, it’s a little more accurate to talk about the economy as mixed-use, both capitalistic and (effectively) socialistic. And same goes for government - the tendency is to think of government as a monolithic entity but that was never the intention. The republican ideal was always to have conflicting government bodies with overlapping interests - federal, state, municipal, etc - which would be in basically constant disagreement and produce something more like a federated (i.e. distributive system).

If there’s an overriding theme to the political and social-minded writing on this Substack, it’s a terror of totalization in virtually whatever form that takes - whether that means the current onslaught of tech totalization (what Jaron Lanier calls ‘digital Maoism’), capitalist totalization in the Milton Friedman model, or, almost needless to say, government totalization as in Fascism or political Maoism. That tendency towards totalization emerges distinctly in the 17th and 18th century and, in surprisingly crystallized form in Britain. Simply put, a variety of technological and sociological changes make a degree of centralization possible in ways that had just never existed in human history. That was a powerful centralized state with a near-monopoly on violence. And that was dominance of international trade, enforced through incontestable superiority of arms. Modes of governance, as in Belloc’s assessment, flopped around greatly - in Puritanism, in monarchist revivals, in republican experiments - but without greatly affecting the underlying structure, which had to do with ever-increasing consolidation of power by the center and totalization of society. By the late 17th century, as Claeys describes it, there was a sort of ‘End of History,’ symbolized by the end of the Puritan regime and the cheeky compromise of constitutional monarchy, which triggered a new ‘age of excess’ not at all dissimilar to the materialistic nihilism that we experienced in the 1990s. And that age of excess was greeted with a similar onslaught of vapidity as in our own era - with Charles II, ‘the pretty witty king whose word no man relies on’ not a bad counterpart to Bill Clinton and the batch of politicians of his time.

In the long-buried utopian writing of the Enlightenment, there was an understanding that the age of excess was a fait accompli - it’s unlikely that any of the authors of the satires Claeys quotes from were actually advocating for ascetic Christian communities or the state of Arcadia. But what they seemed to recognize was that capitalistic totalization, so amusing and apparently innocent in the flippant early Enlightenment, was an aberration not a permanent state. And that the really critical turn away from it wouldn’t be so much the advent of some new political system as a mental switch, the development of a dormant ethic of restraint. “To live luxuriously is but a custom: if it was broken off, nobody would miss it, and evidently it would be of infinite advantage to the society that it were so,” wrote ‘Philadept’ in An Essay Concerning Adepts, one of the satires.

And that, I find, is pretty much exactly where we are at the moment - deficient in an ethic of restraint, absorbed in the custom of ‘luxury at all costs,’ but capable at the same time of finding a certain inner strength and inner freedom of movement, finding in ourselves ways of being that are not driven by materialistic totalization.

AN EXCUSE TO TALK ABOUT JOSEPH ROTH

Not so much new in this write-up of Joseph Roth in Tablet Magazine - basically just a rehashing of literary gossip - but I couldn’t pass up writing about it. Roth, for me, is the purest writer of the 20th century and very nearly my favorite writer.

What do I love so much about him? That he wrote prolifically; that he wrote about everything; that he anticipated, better than most, the terrible circumstances of his epoch but continued to prioritize the personal over the political; that he opened the aperture very wide - felt all experience was subject to writing; that he was intelligent in everything he wrote but at the same time was of the people, that his intelligence was common-sensical, in sharp contrast to the flights of fantasy of the bourgeois intellectuals surrounding him; and that he somehow managed to preserve a peculiar mental equilibrium, going mad, drinking himself to death, at the same time that he continued to churn out very brilliant and very buoyant writing.

“Roth has never gotten the attention he deserves, partly because he was no daring modernist but an old-fashioned fiction writer whose models were Tolstoy and Stendhal, and who is just as voraciously readable as these masters,” writes David Mikics in The Tablet. And that’s true - that goes a long way towards explaining why Roth never seems to make the lists of the greatest 20th century writers while, for instance, Robert Musil does - but has to do with more than just modernist snobbery for Roth’s comprehensible sentences and coherent characters. The reigning sensibility of the period (at least among the modernist mandarins) became ‘art for art’s sake,’ a belief that art was somehow above politics and above ethics and need not sully its hands with any of that. Roth felt that that was a terrible mistake. He was absolutely of his time, he seemed to internalize all the competing sensibilities of the collapsing Austro-Hungarian Empire, he was, as Mikics points out, probably the first novelist to mention Hitler, and he knew vividly, viscerally what was coming with the rise of the Nazis while virtually all of his more famous, more successful friends were in some or other shade of denial. At the same time, though, he never just turned himself over to polemical writing. He was, at core, an artist, a born writer - and, even as he was politically engaged and politically prophetic, his deeper project was to transmute his fraught era into art.

The gossip about Roth is all of a piece - that he was irascible, impossible, that he made a wreck out of everything in his private life, that he was sort of already living on borrowed time when he died, age 44, of severe alcoholism, but that he did everything at the top of his lungs, with full energy, and the demimonde existence fueled the coruscating and surprisingly humane writing.

Before reading Mikics’ article, I hadn’t known the story of Roth’s marriage, which is truly harrowing - constant control, steady abuse, public humiliation, through all of which he inexorably drove his wife mad. That’s of course very hard to forgive but also not so surprising - the sense of Roth is that he was pursued incessantly by demons. Other tidbits are wrenching but a bit more benign - the stories of Roth’s endless confabulations (his origins, his entire war service; he was proud of his inveterate lying, claiming “I learned the real craft of the writer and the confidence man: how to formulate things”), the stories of his torrid alcoholism (a girlfriend claims that, in the ’30s, he spent an hour every morning throwing up).

And the handful of lines quoted by Mikics are a reminder of what a truly brilliant writer Roth was. “Although he was a white-haired cripple,” Roth writes of a character in his novel Job, “he didn’t give up his spite...he stayed alive only to rebel, against the world, against the officials, against the government and against God.” And in a fulmination to his ever-unappreciative employer, the Frankfurter Zeitung, he wrote, defending his feuilletons against the straight political reporting, “I am not an encore, not a pudding, I am the main dish...I don’t write ‘witty glosses.’ I paint the portrait of the age.”

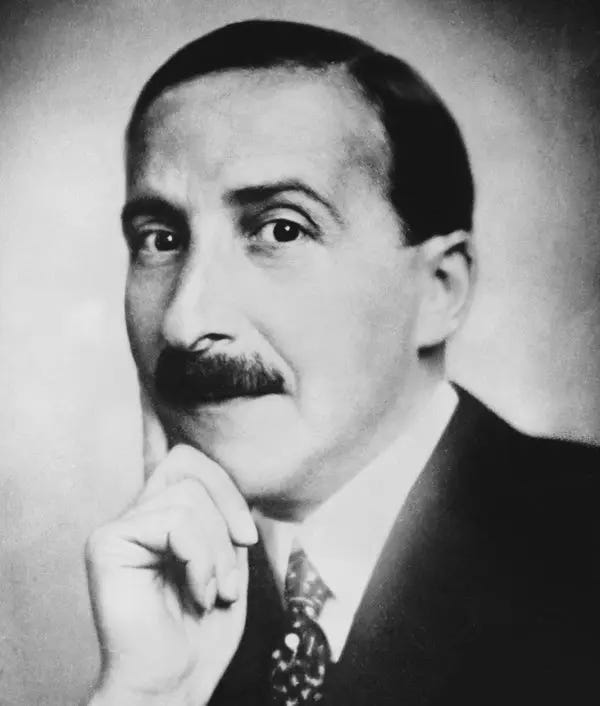

At this stage any discussion of Roth is incomplete without discussing Michael Hofmann. Hofmann, a gifted poet and writer, appointed himself Roth’s amanuensis, dedicating years of his life to translating Roth’s scattered work into English and to advancing his reputation. Hofmann became best-known for a scabrous attack on Stefan Zweig in The London Review of Books - a real bolt out of the blue for most people who thought about Zweig (if they thought about him at all) as the gentle inspiration for The Grand Budapest Hotel, honored with the statue of ‘Author’ in the film’s opening - and probably the only bit of literary criticism that anybody would possibly remember from the 2010s.

But Hofmann’s critique of Zweig - “putrid through and through”; “the Pepsi of Austrian writing; “smooth and mannerly and machined….even in his suicide note” - isn’t really about Zweig; it’s about Roth. In addition to amanuensis, Hofmann had appointed himself Roth’s avenging angel. Roth, in his life, had been condemned to a humiliatingly subordinate role to Zweig. Zweig, who was from a nice bourgeois family, had become, in due course, the elder statesman of Austrian letters, always popular, always prosperous, churning out his boilerplate stories and genteel biographies. And Roth, completely dependent on Zweig both for connections and for money, dedicated his letters to Zweig to fawning obsequiously over him - while bad-mouthing Zweig in the letters he wrote to everyone else.

There’s a wonderful story Hofmann relates about Zweig’s taking Roth to the tailor for expensive new trousers. Roth went through the shopping experience, was duly grateful to Zweig, and then the next day an acquaintance came across Roth in a bar and found him pouring brightly colored liqueurs all over his jacket. “I’m punishing Stefan Zweig,” Roth tersely explained to the friend. “Millionaires are always like that. They always take us to the tailor and buy us a new pair of pants but they refuse to buy us the jacket to go with it.”

So - a very twisted relationship - and Hofmann clearly felt that he could do Roth a favor and untangle it. As he writes of the letters Roth and Zweig exchanged, “Roth’s letters are always uphill. He is always the underdog, always indomitable, always David to the other’s Goliath. By the same token he is always the better writer and he is always in the right. The other is the one with money, power, authority, patronage, prestige. Roth has nothing, is nothing, all he can do is make a noise.” And Hofmann’s collection of Roth’s letters is - actually - one of the funnier books I’ve ever come across, the real-life analogue to Charles Kinbote, Roth writing his obsequious letters, praising Zweig’s writing and magnanimity, asking him over and over again for money, while Hofmann, from the footnotes, annotates his version of what Roth really meant to say/

With Hofmann, Zweig and Roth appear in a kind of parable form - the parable of the true artist and the fake. The conviction shared by Hofmann and Roth (and which I have as well) is that the standard artistic industry - very similar in inter-war Mitteleuropa to what it is in the Anglo world in our own time - tends to be extremely credulous, easily fooled by fakes, of which Zweig is a prime example. There is proficiency, fluency, grace, good manners, even, in Zweig’s case, a genuinely gentle spirit - but no fire, no honesty, no genuine curiosity, no ability to take risks in writing. And Roth was all of those things. As Hofmann writes, “The very quick and fiery and aggressive Roth and the obtuse, decent-minded Zweig are a fascinating - and distressing - study in contrary temperaments….Roth was all instinct. Zweig had none.”

And this is a key part of what literary criticism is. Hofmann is a famously vituperative critic - The London Review of Books ended up publishing no fewer than six letters-to-the-editor of bewildered readers springing to Zweig’s defense and wondering how Hofmann could be so crass as to do close-reading analysis on somebody’s suicide note - but, basically, this is the point of the whole exercise. There is a higher truth in art than acclaim or even craft. It has to do with being really invested in the world as it is (not in the world as you might like to be) and, with ferocity and with love, biting off as much of that reality as possible. Roth understood that about as well as any other artist ever has.

AGAINST CHOICE ARCHITECTURE

And speaking of splenetic critique, here’s one from the irascible Michael Lind torching another professional nice-guy, the policy ‘wonk’ Cass Sunstein.

I don’t have a huge amount to add to this, other than appreciating Lind’s laugh-out-loud funny writing (particularly, his use of the highly-deployable term ‘midwit’) - I just don’t know enough about what Sunstein is really up to. For me, this article is kind of a personal litmus test for where I’ve shifted to in my political orientation. At the start of the Obama administration, Sunstein and his wife Samantha Power seemed like the cool kids, Power exerting a muscular doctrine about how the United States could do the most good in the world, Sunstein as the benevolent bureaucrat, choosing to helm the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, as opposed to much glitzier-sounding positions, with an eye to cutting through red tape and putting the principles he’d developed in his best-selling Nudge into action.

I was watching too much of The West Wing around that time - and that’s how I imagined government: kick-ass policy wonks walk-and-talking their way to a better world. And now, years later, dealing with the ruinous state of American democracy, it is worth asking some hard questions about the Obama administration - what the failures in political philosophy and models of governance were - and the Power/Sunstein power couple is a reasonable place to start. Power’s doctrine of intervention has turned out to be the more obviously questionable - giving us Libya and Yemen. But there may be much to criticize - and Lind criticizes all of it - in Sunstein’s ‘libertarian paternalism.’ As Lind argues, libertarian paternalism is first of all a ‘contradiction in terms’ - actually, it simply is “government paternalism.” And the policies advocated in Nudge have a very creepy aspect to them. The whole theory is based around tricking people - ‘choice architectures’ - in which everybody is ostensibly free to choose whatever they want, but pressures are so aligned that they inevitably end up making the ‘right’ decision. “For example, in public school cafeterias,” writes Lind in a recap of Sunstein, “healthy foods would be placed up front, and unhealthy snacks and desserts, rather than being banned outright, would be available but semi-hidden, to trick youngsters into going for fruit rather than cupcakes.”

The sense was that Sunstein achieved much less of the Nudge vision than he would have wanted to at OIRA. Obamacare had the hallmarks of Sunstein’s approach - and the difficulties with its rollout, the inability of the public to understand the rules or how to navigate them, seems to have been part of the impetus for Nudge’s sequel, named of course Sludge, which is all about the art of reducing paperwork. But that philosophy has stayed with us and, as far as I can tell, is deeply embedded in the technocratic state that now is virtually synonymous with the Democratic Party - in, for instance, the approach to vaccines, in which there was never a national vaccine mandate but by ‘choice architecture’ it became more and more impossible throughout 2021 to have a normal life without being ‘guided’ to the vaccine.

And the more I see of ‘libertarian paternalism’ the less, obviously, there is to like about it - this odd sensation, in more and more aspects of my life, that I’m being herded, compelled through some sort of too-clever-for-its-own-good soft power, to ‘optimize’ my behavior. (The examples that come to mind aren’t necessarily in the domain of government - it’s things like needing to have an iPhone with me in order to order food off a menu, finding myself signing up for CLEAR at the airport with its ridiculous intrusion into ‘biometric data’ as a best-fit option for avoiding long lines - but this sort of ‘choice architecture’ seems to be the spirit of the times.)

Lind’s ‘liberal nationalism’ - a heterodox position that, as per a New York Times article, “defies the usual political categories of left and right, liberal and conservative” - is, at the moment, more my cup of tea. That means returning to basics, attempting to restore power to elected officials as opposed to what Lind calls “the all-wise benevolent caste of mostly unelected choice architects in government offices who allegedly understand the interests of ordinary people better than ordinary people themselves,” and at the same time scaling back on and streamlining government as opposed to the odd technocratic contortions that Sunstein proposes.

All of this is a bit painful to write. Liberal myth-making towards the end of the 20th century fixated on the image of the super-wonk, somebody with impeccable credentials and noble intentions, who could cut through partisan gridlock and craft intelligent, far-sighted policy. More than anybody else - other than Josh Lyman - that type was embodied by Sunstein. And, as far as I can see, the result is anti-democratic. Lind calls it “secretive, manipulative, technocratic despotism.”

The reality, as Lind seems correctly to intuit is that there are no technocratic shortcuts - they just lead to more technocracy. And ‘nudge,’ which seemed so cool in 2008, is just another way of saying ‘regulation.’

Read everything here, including the links fascinating.

I'm wondering what you think of William Gass and if, in some way, he may be hitting where you were going on the literary side of subjects in this broad essay and maybe even in the one before.

Here's a quote for you gnaw on: "Gertrude Stein wondered more than once what went into a masterpiece: what set some works aside to be treasured while others where abandoned without a thought, as we leave seats after a performance; what there was about a text we’d read which provoked us to repeat its pages; what made us want to remain by its side, rereading and remembering, even line by line; what led us to defend its integrity, as though our honor were at stake, and to lead it safely through the perils that lie in wait for excellence in a world where only mediocrity seems prized. She concluded that masterpieces were addressed, not to the self whose accomplishments might appear on some dossier, the self whose passport is examined at the border, the self whose concerns are those of the Self (I and My and Me and Mine); but to the human mind, a faculty which is everywhere the same and whose business is with universals. Masterpieces teach that human differences are superficial; that intelligence counts, not approved conclusions; that richly received and precisely appreciated sensations matter, not titillation or dolled-up data; that foreplay, not payoff, is to be preferred; that imagination and conceptual solutions, not ad hoc problem solving, are what such esteemed works have in common. And we, who read and write and bear witness and wail with grief, who make music and massacres, who paint in oils and swim in blood—we are one: everywhere as awful, as possibly noble, as our natures push us or permit us to be." –William Gass, _The Test of Time_

Love that voluptuary! Thanks!