Curator

Should We Write About Mass Shootings?, Are We Evil or Not-Really-So-Bad?, Are We Too Clever?

Dear Friends,

I’m sharing the ‘Curator’ posts for the week. These are riffs on articles I’ve wanted to spotlight from the ‘artistic/intellectual web.’ The point, as much as anything, is just to pay attention to good and/provocative writing wherever I come across it. I’ll be in the habit of noting that I’ve turned on the ‘paid option’ for subscribers. There’s no actual benefit, at the moment, to getting a paid subscription! - but I’d appreciate it if you considered the option (and, with time, I’ll add features for paid subscribers).

Best,

Sam

SHOULD WE WRITE ABOUT MASS SHOOTINGS?

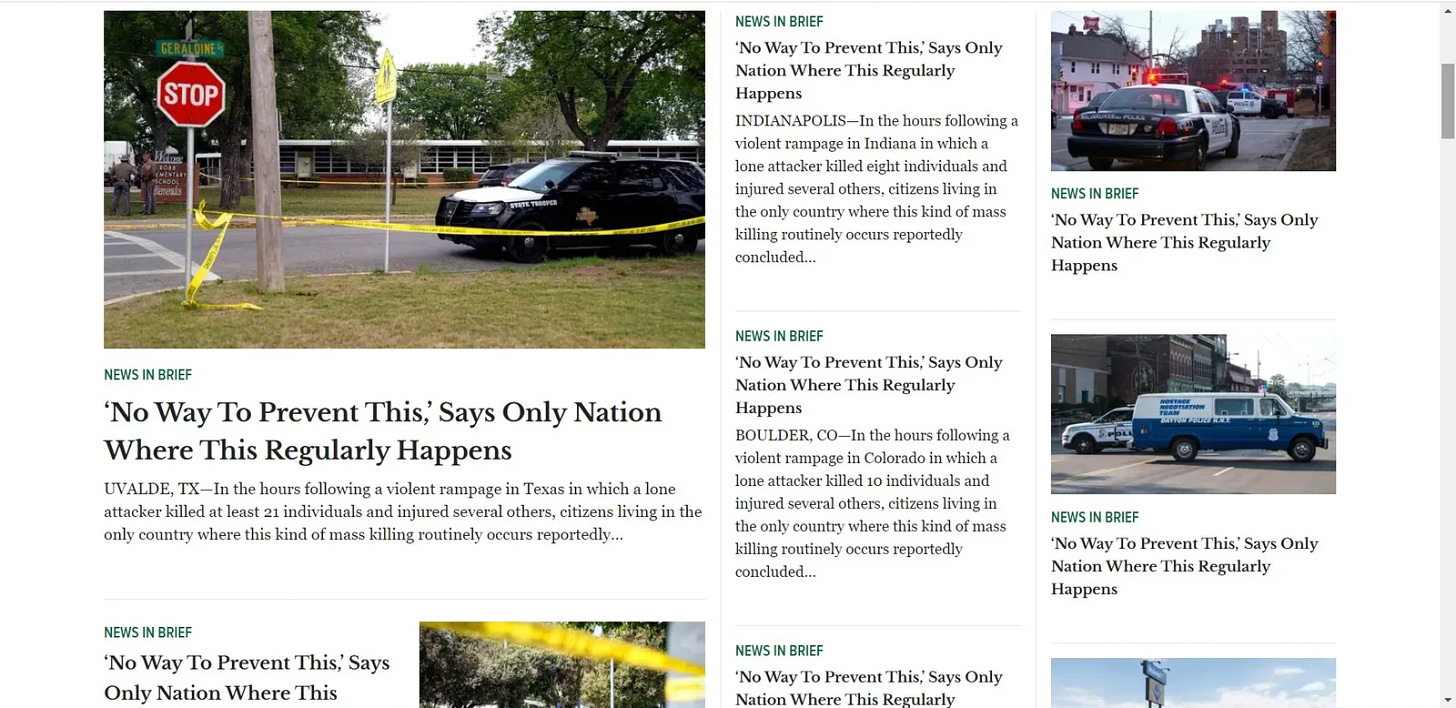

In writing about news and culture now, it’s necessary to write - pretty regularly - about mass shootings. Which is just about the last thing in the world that I want to write about. There are a few things that have to be stated and restated. One is that - if you haven’t noticed - we are now at 611 mass shootings for this calendar year, according to the Gun Violence Archive. (The year 2000, as a point of reference, had five.) I can remember when mass shootings, particularly in schools, were an incomprehensible, massively-reported event - like an intrusion from some neighboring ‘demon dimension.’ Now you often need to scroll far down a national newspaper even to get the news of the most recent shooting. (The recent journalistic trend has been to bundle the stories together - reporting, for instance, on the spate of shootings that occurred over a given weekend.) I can also remember when the assumption was that the shootings were an aberration - the particular way that the screws were coming loose out in Crazytown (as recently as the early 2010s, Obama had a Spockish tendency to compare the risks of dying by terror attack to the risks of dying by a fall in the bathtub). Now it’s become clear that they are the fact of public life in America - every gathering, every visit to a public space, accompanied by the perpetual fear that a shooting could happen; everybody quietly preparing for it in their own way, sort of how, when I was growing up, I learned to pat myself down every so often to check for pickpockets. The other point that needs to be stated and restated is that gun control legislation has yet again stalled. The Onion is a model to all of us by running the same headline every time a mass shooting occurs: “‘No Way To Prevent This’ Says Only Nation Where This Regularly Happens.” I must say that I have no idea what argument a Republican legislator could possibly make to oppose a ban on assault weapons - like, if I were in a Lincoln-Douglas debate and I were given that side of the argument, I just literally wouldn’t be able to come up with anything - but there they are, elected officials pocketing their cash from the NRA and claiming that the solution to gun violence is…..more guns.

Anyway. There really is nothing smart to say about mass shootings - and my point in this piece is to argue that one shouldn’t even try. Sam Kriss has an essay in The Point arguing the opposite - claiming that mass shootings have become the air-we-breathe reality of American life and that it’s incumbent upon American artists (Kriss is thinking about novelists in particular) to contend with the mass-shooting era. Kriss, a gifted essayist, is very sure of himself and gets very worked up on this point. “The American novelist is standing in the middle of a charnel house, with blood dripping off the walls, writing little autofictions about the time someone was rude to them in their MFA,” he writes.

I’m normally sympathetic to arguments like Kriss’ - I believe that courage is a primo virtue for writers; that it can be necessary, in order to create good art, to deal with the most difficult and most frightening with subject matter; and I’m as hateful as the next essayist towards “little autofictions about MFA programs.” But there is something in Kriss’ overheated, overconfident essay that bothered me and made me feel that he had a crude idea of what literature is supposed to do.

What Kriss is supposing is that literature is a big tent and can take in any aspect of the human experience, however abhorrent. This is part of a valid, venerable school of thought - it’s been brilliantly articulated by such spelunkers of the psyche as Dostoevsky and Céline - and Kriss assumes that if the mass shooting phenomenon is part of the psychology of our era then artists must deal with it and deal with it employing the usual techniques of art i.e. empathy and an unblinking acceptance of reality, however unpleasant reality might be. And Kriss is bold enough to lead the way in the direction he has in mind. “There was a time when I also wanted violence. I, too, was a slightly weird kid….And more than once, in my early teens, I had the same fantasy as the shooters. What if, rather than being quietly miserable, I killed people instead?” Kriss writes.

Credit goes to Kriss, I suppose, for having the nerve to say that out loud. And he runs through his personal honor roll of artists who have confronted the age of mass shooting head-on - Gus Van Sant, who made a film from the perspective of the Columbine killers; DBC Pierre, Michel Houellebecq, Lionel Shriver, Don DeLillo, Tony Tulathimutte, Amia Srinivasan; Wesley Yang, who recast mass shootings in terms of ethnic identity, and wrote of the Virginia Tech shooter, “Millions of others reviled this person, but my own loathing was more intimate. He looks like me, I thought.”

But, as Kriss summarizes each of these works, he seems to sense something off about all of them. Each grounds a story of unimaginable evil in some familiar sociological trope - Tulathimutte’s short story ‘The Feminist’ is about the hypocrisy of a certain type of “male-feminist ally”; Yang’s essay is about anti-Asian discrimination in America; Srinivasan’s is about vestigial patriarchy and a male sense of entitlement to sex as refracted through a violent incel movement. Kriss starts to get frustrated. “Srinivasan and Yang have perfectly reasonable ideas about why these things happen—the problem is that these things are not reasonable,” he writes. “They are outside the remit of the essay, a form in which things are supposed to be broken down into comprehensible pieces and coherently analyzed.”

Kriss’ solution is to forego the essay and to insist on writing fiction instead. “There are a basically limitless number of novels about the internet and what it’s done to our brains. So where is the mass-shooting novel?” he howls at America’s ranks of shiftless novelists. But Kriss’ acknowledgment of the limits of the essay - that the essay is a fundamentally rational form and cannot deal with the irrational - could be similarly applied to the novel. The novel is a psychological art form - there is a point of horror, I would submit, where the novel loses its standing, which is the point where human psychology enters into a sort of psychic black hole and no longer becomes psychology at all but tips into monstrousness.

That this point exists is something that many very great artists - people who believe in the power of art; people who are no shrinking violets when it comes to the world’s miseries - have been willing to acknowledge. It’s what underlies Adorno’s injunction that there can be no poetry after Auschwitz. It’s what J.M. Coetzee is getting at in a fraught passage in Elizabeth Costello where he writes (through his altar ego Elizabeth Costello he is critiquing a visceral torture sequence in Paul West’s The Very Rich Hours of Count von Stauffenberg), “It was obscene because having taken place such things ought not to be brought into the light but covered up and hidden forever.” It’s what Emil Fackenheim was claiming when he tried to cut off discussion of Hitler’s psychology and Hitler’s motivations, insisting that Hitler be treated as an “eruption of demonism in history” and, therefore, as fundamentally unfathomable.

I’m aware that I’m falling into the polemic quicksand of the reductio ad Nazism (i.e. thinking about everything by analogy to Nazi Germany), but, as usual, there is something to be learned from that. The lesson is that, somewhere out there, there are limits on what is permissible knowledge - it’s really not ok to marinate, even fictionally, in all the details of von Stauffenberg’s torture without becoming somehow complicit with the torturer; it’s not ok to possess Nazi paraphernalia; to coo over Hitler’s baby photos, as per an ’90s intellectual tempest-in-a-teapot; to consider that Hitler ‘might have had some good ideas’. And the current wave of Holocaust kitsch - Jojo Rabbit being the most egregious recent example - make clear just how aesthetically criminal it can be to venture blithely into what really should be sacred and forbidden territory. The question becomes where the veil is drawn - what events, what states of mind, are so horrible that we cannot enter into them, cannot empathize with them.

Mass shootings, I would suggest, are one of them. There isn’t some healing to be had from acknowledging that everybody is potentially violent or through some attempt to link mass shooting with broader cultural trends (discussions about ethnic identity or sexual entitlement, for instance). I was very affected, when I read it, by Dave Cullen’s book Columbine - a conscientious, concerted attempt by Cullen to get to the bottom of what the shooting was about. Cullen, who kept reporting in Littleton for years after everybody had left and talked to everybody, went through the media-assigned culprits for the shooting - Marilyn Manson, the Trench Coat mafia, a high school bullying culture, etc - and, one by one, dismissed all of them. The problem, he concluded, was that Eric Harris was a born psychopath. Case closed.

What I’m saying is not that art cannot deal with the era of mass shootings. That is our reality; we all have to deal with it in one way or another. The point is a little subtler and that art is not compelled, as in Kriss’ framing, to tackle the subject head-on from the most trenchant vantage-point (which, in this case, would naturally be first-person-shooter POV). That’s just not exactly how art does its work. The best novel about 9/11 was mostly about cricket. The best novel about World War I was about hooking up with the gamekeeper. Art tends to draw a blank around horror and trauma themselves - the word ‘unspeakable’ is a very important, very evocative word - but to be very good at documenting the ways that a catastrophe changes everything in its gravitational orbit.

We are in the era of mass shootings. There may well be a great mass-shooting novel that will come out of it. (In the era of Hitler, there were many, many great works of art that one way or another involved Hitler.) But there is a difference between that and, say, writing from Hitler’s perspective - which is (from my perspective) impermissible. Kriss seems to be dealing with all horror as if it’s just another iteration of aesthetic theory. “Fiction has been increasingly turned towards hyperobjects,” he writes with enthusiasm - the idea being that an event, like a mass shooting, can be understood (and written about) more in the abstract, as a sort of bloodless manifestation of collective psychology. But his preference, really - and by analogy to Dostoevsky - is for the first-person narratives of the shooters themselves. “I read them all,” Kriss writes, in another nervy moment. “I could pretend that it’s because I’m trying to understand….[but] that would be a lie. I read them because I enjoy them.” And his honor roll, I’m sorry to say, extends to the manifestoes themselves. Elliot Rodger’s is written up as “possibly the greatest of the mass-shooting manifestos, the most studied, the most influential.” And this to me perfectly encapsulates why some moral boundary needs to be drawn, why some knowledge needs to be prohibited. Rodger’s manifesto isn’t “the greatest of anything.” It’s a document of a young man turning into a monster. I don’t think reading it should be banned or something - it’s possible to read it in the way scholars read Mein Kampf, as a warning or lesson. But I do think it’s very important to not enjoy it - do that and not only do you normalize something that absolutely must not be normalized but you cross some threshold in yourself, you tip over into the monstrous.

ARE WE EVIL OR ARE WE NOT-SO-BAD-AS-ALL-THAT?

Jackson Arn’s ‘Thinking The Worst Of Ourselves’ in The Hedgehog Review (not actually new but on the website) makes a nice pairing with the Sam Kriss piece and is closer to my point of view. Kriss is arguing that we are all mass shooters somewhere deep inside of ourselves and the path to healing (or at least truth) is to start by acknowledging that. Arn contends that the problem is exactly an assumption like Kriss’ - the odd tendency to think the worst of ourselves.

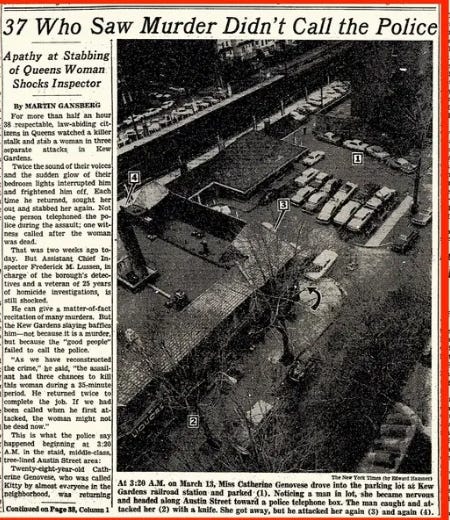

Like Rutger Bregman in his very similar Humankind: A Hopeful History, Arn attacks the soft underbelly of the We-Are-Wicked camp - pop psychology. We-Are-Wicked, as both Bregman and Arn argue, found a pseudo-scientific basis through a series of mid-20th century studies - the Milgram and Stanford Prison Experiments - and then through an accompanying raft of shock-you-to-your core stories, Lord of the Flies, Eichmann in Jerusalem, Martin Gansberg’s Kitty Genovese story. As Bregman, Arn, and a later generation of critics have been astute in pointing out, all of those studies and stories are so flawed in their different ways that they should, at the very least, be stricken from the record, withdrawn as evidence for the prosecution. The Milgram experiment had serious methodological flaws. The Stanford Prison Experiment was, as Bregman writes, “a hoax,” and was designed to prove a proposition. Gansberg’s story was a piece of yellow journalism and was more than fully contradicted by the facts on the ground (not least the bystanders who actually did call the police). Lord of the Flies was, after all, a novel - and its thesis was pretty effectively disproved by a real-life incident, in which a group of teenage boys actually were marooned on a Pacific Island and developed a functioning society and took care of one another until they could be rescued. Eichmann in Jerusalem was a more complicated text than it’s generally remembered, but it was marred (at least in the ‘banality of evil’ section) by Arendt’s being to some extent taken in by Adolf Eichmann’s trial defense and in-the-docket behavior. As Arn judiciously writes, “The first thing that needs to be said, then, is that I don’t know what these cases prove. What I do know is that all three have been profoundly misinterpreted, beginning with their original chroniclers.”

So toss out pseudo-science and pop psychology and we’re sort of back to where we started - God sitting around beholding what He had created in humankind and thinking that it might be a good idea to send a flood to destroy the world (and occasionally being talked out of this sort of thing by a smooth-tongued Patriarch). Arn is more careful than Bregman, who overplays his hand - and ventures past into scientific simulacra of Nazism into Nazism itself and argues that the Danish resistance to deportations proves that civil societies cannot be cowed by totalitarianism; that the British resilience to the Blitz proves that society cannot be torn apart by terror. (And no matter that there were many other societies in the same period of time Bregman is talking about that enthusiastically participated in deportations, that really were torn apart by the horrors of war.) But there is a passage in Humankind that felt more or less right to me - and that mirrors the point that Dave Cullen was making (cited above) about Columbine.

Bregman is in typically overzealous mode, citing the study of Colonel Marshall, who found - encouragingly for the We-Are-Not-So-Bad-After-All camp - that the majority of soldiers in combat never fired their weapons even when they were under direct attack. Bregman concludes from this that we are such cuddly, Ferdinand-the-Bull-ish creatures that most of us, even in war, even in conditions of self-defense, wouldn’t open fire (which, again, must be very surprising to the very many soldiers in world history who, absolutely, unequivocally, have come under sustained fire, no matter what Colonel Marshall’s study might say). Bregman knows that he has some explaining to do and writes that the vast majority of combat fatalities are the result of relatively small groups of hardened soldiers who have little difficulty pulling the trigger and whom their commanders regard as reliable. So. Yes. That’s a compromise that I can sort of agree on. The thing to be concerned about isn’t so much Marshall’s band of hapless recruits as elite, crack soldiers; not so much ‘the inner Nazi in all of us’ as actual Nazis, who efficiently organize themselves and then wreak havoc from there.

The really terrible concern - and this, as Arn aptly notes, is what Arendt was actually writing about - isn’t so much a philosophical or psychological question as a sociological one. It’s not about the ‘banality of evil’ as some permanent psychological condition - human beings evil in an intrinsic state of nature. It’s clear enough that evil exists, enters into society by one means or another, and the critical question is whether it’s possible to construct bulwarks against it - through social systems but, above all, through moral integrity and personal courage - that can intercept some particular variety of evil before it becomes normalized and commonplace in a population. As Arendt writes, “Evil in the Third Reich had lost the quality by which most people recognize it - the quality of temptation. Many Germans and many Nazis, probably an overwhelming majority of them, must have been tempted not to murder.…But, God knows, they had learned how to resist temptation.”

The next turn of the wheel from Milgram and Stanford - the turn of, for instance, Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men - reflected this statement of Arendt’s (far more nuanced than her ‘banality of evil’). The issue was about how people were able to keep their moral compass in circumstances where the moral landscape had been deliberately, malevolently distorted. For most people, as it turns out, there really was a fraught inner dialogue, a period of resistance and acclimation. In terms of thinking about the essence of morality, the terms aren’t really a high school debater’s ‘are we good’ or ‘are we bad.’ There seem to be variety of powerful moral intuitions that allow us to cooperate with one another, but these are limited and far from foolproof. Morality turns out to be sustained hard work - a constant questioning of oneself and of one’s surroundings, and part of that is a questioning of tough-talk-sounding premises that are actually deeply distorting. “There is something intoxicating about the possibility that morality is a paper-thin lie and barbarism is the truth of the human condition,” writes Arn. “That this possibility might be correct is disturbing; that so many people seem to wish it were correct, far more so.” Let ourselves believe that we are wicked - as a certain strain of ‘common sense’ would have it - and that proves a self-fulfilling prophecy.

THE MALADY OF CLEVERNESS

And one more piece from a strong issue of The Hedgehog Review - Alexander Stern on the pervasive nuisance of cleverness. Stern is thinking mostly about Twitter and contending that a prevailing mode of discourse on Twitter - “where cleverness has become something like a currency, hordes of commenters and commentators competing for likes and subscribers with world-weary analyses and smug jokes” - is symptomatic of a larger malady, an inability to be earnest about anything.

Stern’s is a heartfelt, intelligent essay. I agree with it completely and only have a few addenda to tack onto it. The obvious objection would be that the essay feels ten years or so out of date, that the issue at the moment is too much earnestness online, that Twitter hordes can’t take a joke are determined to scrutinize all possible everyday interactions for evidence of moral deficiencies. But that’s a bit like asking whether We-Are-Evil or Not-As-Evil-As-All-That - multiple things can be true at once; and the cleverness is, if not a full-on scourge, then at least a nuisance.

What Stern is really right about is to see cleverness as a manifestation of modernity and of the distinctly modern phenomenon of alienation. “There is an affinity between cleverness and the outsider,” he writes. “The diffusion of cleverness in modernity is, therefore, closely connected to the diffusion of alienation.” And the history of cleverness can be traced in several iterations - the 19th century flâneur, who pioneered the idea that detached observation could be a permanent state of existence; the 19th century parlor detective, secure in the armature of reason and of bons mots; the 20th century gumshoe detective, astute enough to notice that the belief in hard-boiled reason is probably a screen for emotional deficiency but sticking with that hard-boiled reason for lack of any better ideas; the stand-up comedian taking for granted the alienation of modern life and complacently assuming that canny observation is about the highest state that can be hoped for (“it is no accident that Seinfeldian cleverness tends to thrive in spaces like the airport where the individual is most atomized and the absence of community most palpable,” Stern writes); and the social media poster attempting to weaponize their own alienation. “The game, in effect, is this: who can appear the most above it all?” Stern writes.

To a remarkable extent, the dual phenomena of detective and flâneur have a single origin point - in the fervid imagination of Edgar Allan Poe, who introduced the modern-day detective with ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ and the flâneur with ‘The Man In The Crowd.’ My usual way of thinking about this phenomenon - call it the all-pervasiveness of Poe (he gets credit also for science fiction, for horror, and for a certain totalizing streak in literature) - is that the 1840s and 1850s were really a crucible period, when modernity was taking its distinct shape and that visionary artists like Poe (also Baudelaire, Dickens, etc) were able to anticipate its direction. More and more, I’m coming around to thinking that the opposite is true - that Poe essentially fever-dreamed the entire course of modernity and we all find ourselves caught in a loop of his psyche.

Taking that idea seriously for a moment, the mechanism of it would be as described by Stern. Poe and those that followed him - Baudelaire, Conan Doyle, etc - assumed a fully deracinated urban individual, with no community, no theological purpose, but armed with science, logic, and a clever-dick assurance that we are dealing with, in a sense, a complete data set and that the answers can all be worked out if one is smart enough. This particular personality type - INTP, if one goes for these sorts of things - then becomes the standard-bearer for and arbiter of truth. The most consequential variation of that is in the modern archetype of the mad scientist - who will pursue iron logic well past the point of logical insanity. (There’s an interesting article, here, by the way, on John von Neumann, who embodied that sensibility more than just about anybody, who dedicated his life to “transforming problems in all areas of mathematics into problems of logic” and to establishing a ‘fortress of logic’ in mathematics that would be free of all paradox and then ended up as a fervent proponent of Mutually Assured Destruction, a paradoxical doctrine if ever there was one.) But in terms of thinking about popular imagination and patterns of personal identification, Stern is right to link this mindset above all with the figure of the detective. Towards the mid-20th century, the detective goes through a curious transition. The detective seems to lose the Victorian buoyancy of Sherlock Holmes, to no longer be satisfied with solving crimes for their own sake. The detective becomes more of a brooder, drinks harder, has more of a sense of being compelled to wander onto the dark side over the course of solving a case; but, with ambivalence and misgivings, settles always on the side of law-and-order, duly puts away ‘the criminal,’ discharges his ‘duty.’ The whole genre of noir becomes a beautiful metaphor for how the figure of the outsider gets domesticated - never losing the essential outsiderness, alienation, moral ambivalence, but convinced to participate in, broadly speaking, the security state - and convinced precisely out of an appeal to the detective’s cleverness. (The assumption is that, although it’s a close-run thing, it’s more fun, at least from the standpoint of logic, to be the one solving the crimes as opposed to the one committing them.)

In some sense - at least in the domain of literary analogy - this is how our whole system sustains itself, to the extent that it does. We have dismissed faith as an intellectual superstition (that intellectual shedding occurring, really, right in the watershed period of the 1840s and ’50s). We have elevated logic - cleverness - into the highest good, and then the moral life of the society turns into a dance in the dark of trying to determine if one is putting one’s logical abilities in the service of good or not. But, as Stern writes, the whole premise is a bit shaky. “This kind of cleverness that cuts through illusions can become its own kind of illusion,” he writes. And, as is so often the case, it can be very useful to look back at the intellectual genesis of a pervasive idea. Poe and Baudelaire knew that there was something sick about the hyper-rational sensibility - and dealt with it as a form of abnormal psychology. There is something very unnerving about betting all of one’s chips on logic - the close planetary calls involving von Neumann’s ‘game theory’ logic are evidence enough of that - and the work now seems to be about re-racinating, re-enchanting, restoring faith (no easy matter once one has lost it). That work occurs on the level of individual conscience and of social discourse - it is not at all trivial of Stern to zero in on a spate of cleverness in Twitter discourse - and is basically about learning to access the heart, refusing to believe the never-very-sincere or thought-through claims of science and logic that there is nothing else.

The problem with trying to novelize mass shootings from any perspective is that one (in this case Kriss) seems to assume that one can 'get to the bottom' of the motivation or consciousness of the perpetrator when in fact there is no bottom, only a void. The corollary to this might be: “Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

The Man of the Crowd is a fantastic, spectral work from the opening epigraph, to its first sentence with the quote ('it does not permit itself to be read') to the last sentence which includes the same quote. Which conjures up: 'Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.'