Curator

The Point of Literary Criticism, Longtermist Follies, Sex Positivity and the Prudes

WHY LITERARY CRITICISM MATTERS - OR USED TO

A lovely old-fashioned piece of literary criticism in The Baffler, a tour, via a recent collection of Terry Eagleton’s writing, of leading strains of 20th century literary criticism.

I find the central premise of it haunting, the idea, as John Merrick writes of metaculture, that “one can detect in the dominant forms of culture….the spiritual health of the society that produced it.”

I think this has always been my underlying conceit when dealing with literature or literary criticism - although I can’t remember ever seeing it put so starkly. This idea is what drives the almost-always dyspeptic tone of literary critics of the old school (Merrick in The Baffler piece particularly singles out T.S. Eliot and George Leavis in this respect). There is some ethical imperative to hold to standards, to insist on a kind of narrow church of aesthetics, even at the risk of opening oneself to the charge of snobbery, because the stakes actually are very high - “the very life of the nation itself,” as Merrick puts it. Letting artistic standards slip means moving into an era of decadence, and some kind of moral lacuna in art and culture will sooner or later lead to a rot in politics itself.

Erich Auerbach probably illustrates this idea more vividly than anybody - the string of texts in Mimesis, each representative of the wider culture of its era, each speaking to the differing capacities of people in various eras to effectively understand themselves or interact with the world around them. The falling-off from Homer to Gregory of Tours is the most haunting instance - a fairly clear case of the portals of the mind closing, of a brave, forthright interaction with external surroundings replaced by superstition.

The premise of an article like Merrick’s, which is a summation of Terry Eagleton’s career, is that some similar cultural decadence may have set in during the second half of the 20th century. This is what the Oxbridge mandarins were railing about with their famous snobbery - I.A. Richards, for instance, speaking apocalyptically about the loudspeaker and the cinema - but, from where I’m sitting, it’s hard to say that they were exactly wrong. The usual culprit is post-modernism - and all the critics in the Baffler piece are right on the fault-line of post-modernism, of seeing in its ethic of relativization a fatal undermining of core aesthetic values. And, since these critics tend to be no fun at all, they see an ever darker threat from pop culture and Americanization, a great flattening of discourse, the logic of the commodity driving out every other mode of valorizing a created object. “The one unifying feature of each of these writers is their deep cultural pessimism,” writes Merrick.

And that seems to be pretty much where we are now. ‘Art’ mostly means the marketplace. The chattering from among the ‘high-brow’ is mostly just relativization - a ready-at-hand stand-in for philosophy. And the works that seem to unite everybody, that get through the bottleneck, are pretty much just schlock, brazen or violent or shocking enough that they are at least unignorable (I’m thinking about something like Édouard Louis or Ocean Vuong with the macabre, straight-faced insistence on the terribleness of life).

The last great turn of the critical wheel in Merrick’s account was from the study of literature to the study of regular life. “Culture is ordinary,” wrote Raymond Williams - and Williams and Eagleton together represent a curious hybrid, the high-brow critic applying critical techniques to perfectly ordinary modes of cultural expression with an aim to both defend the ordinary from snobbery and to somehow elevate the ordinary, make it sacrosanct, create a new alliance between the intellectual and the avowedly philistine

And the sense is that that project didn’t quite work out - as the Oxbridge mandarins would have anticipated, as Eagleton himself came to acknowledge by the 1980s. The issue, I think, is that pop culture simply created a domain so all-encompassing that real literature was excluded from it. The project that the modernist critics from Richards onwards had in mind was to see literary criticism as a kind of older brother to the culture at large, but for that to work required some common ground between the domains, say in the acceptance of certain socially unifying texts. That’s what critics like Eagleton and Zizek found so exciting in the mix of high and low in ‘blockbuster’ novels or in the period, starting in the ‘60s, when popular film suddenly got really good. But I don’t see that as being a particularly promising direction any more. Simply put, the culture decided that it could live without literature; that high-brow criticism was just snobbish rather than impressive. And if that’s how it is, that’s how it is. High culture simply has no more connection to the culture at large and isn’t accountable to it - and, actually, there’s something liberating in that. Probably, the culture itself will be fine - but that’s basically a political question and, from a cultural vantage-point, contingent on certain kinds of social myth-making from which literature is by this stage wholly excluded. High culture exists - but only for those who happen to enjoy it. It functions now as a separate domain, a walled garden, and it’s likely to be that way for some prolonged period of time.

THE ADVENT OF LONGTERMISM AND BIG HISTORY

Longtermism is one of these ideas that seems to have been floating around aimlessly for a while and then, suddenly, has a grasp on the collective psyche. The proponent of this sort of thought forever was Peter Singer; now it’s William MacAskill. And if Singer always had a Eugene Debs or Ralph Nader kind of vibe to him - the ascetic radical making everyone feel bad for spending $10 on a movie ticket - MacAskill gives a more polished impression, a sense of rhetorically backing into the stringent ethical strictures of Longtermism in a way where its really startling conclusions have an aw-shucks-why-not simplicity to them.

The New Yorker has a sneakily ad hominem attack on MacAskill, which seems like a puff piece most of the way, dwelling on MacAskill’s saintly qualities, his personal sincerity and earnestness, before moving on to the ways in which Longtermism and its precursor movement Effective Altruism have sold themselves out to Big Tech. That piece reads as more of a parable of good-intentions-and-the-road-to-perdition - the relentlessly ascetic MacAskill somehow finding himself awash in money and unable to recognize the degree to which the movement’s “new proximity to wealth and power” had warped his thinking. Meanwhile, operating more in the realm of pure ideas, Kieran Setiya in the Boston Review has a very convincing takedown of Longtermism. And, in Aeon, Ian Hesketh has an equally lucid case against Longtermism’s ideological counterpart, Big History. I’m mostly just echoing Setiya and Hesketh‘s point - a plea for common sense, humility, a suspicion of anybody who is trying to establish narrative through-lines leading to the remote past or distant future that, oh by the way, generate counter-intuitive and non-negotiable ethical imperatives in the present.

The main issue to understand here - and both Setiya and Hesketh are good on this and MacAskill almost willfully obtuse - is that all of this is a theological question and is not ultimately about practical philosophy and certainly not mathematical modeling or statistical probabilities as MacAskill’s crew likes to pretend.

MacAskill comes up with a remarkably simple formulation of ethics: “Future people count. There could be a lot of them. We can make their lives better.” Not so surprisingly, given the current climate, this idea is backed up by two apparently distinct but oddly convergent discourses, social justice and dataism. In terms of the requisite social justice superegoism, MacAskill writes, “Future people are utterly disenfranchised….They are the true silent majority. And though we can’t give political power to future people, we can at least give them fair consideration.” And to support his conclusions, MacAskill has recourse to some trusty validators: “a decade of research, including two years of fact-checking, in consultation with numerous ‘domain experts.’” And here we are, back in the familiar stew, technocratic academic experts plus our social justice conscience yielding some kind of best-fit utilitarian solution that just so happens to align with the initial intuitions of the person making the case. As MacAskill nonchalantly puts it, “The practical upshot of longtermism is a moral case for space settlement.”

That goes, I suspect, a long way towards explaining why longtermism is suddenly so mainstream - the space obsessions of the tech crowd finding their philosophical justification. As far as as I can tell, the vision for space exploration comes more or less from Jeff Bezos having watched too much Star Trek as a kid. The idea of trillions of people in their little consumerist pods doesn’t sound particularly appealing to most people, but it does to a sliver of the tech industry - Elon Musk, for instance, described MacAskill’s newest book as “a close match for my philosophy” - and now, lo and behold, that argument is framed as a probability-driven ethical imperative. If there is a risk of the species’ extinction, runs MacAskill’s argument, and we hold that the species’ continuance is a fundamental good, then any action we take must be evaluated by whether or not it adheres to that ethic of continuance. Staying on earth means putting all of our eggs in one basket - a utilitarian no-go - and space colonization becomes not just a good idea but an ethical absolute.

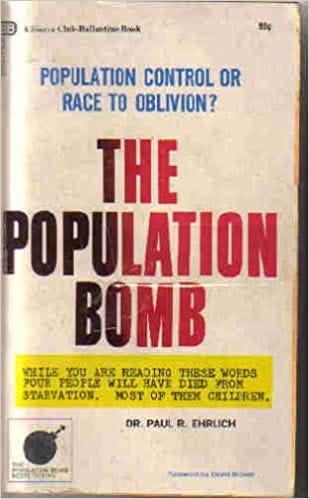

I have to say that I find this outlook a bit cheerier than the usual strictures of philosophers wading into what Setiya calls “the deep, dark waters of population ethics.” Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb is probably the most notable contribution to this field and reaching the unfortunate and honestly genocidal conclusion that we have to diminish the global population as fast as possible to avoid mass starvation, while Peter Singer’s interdiction of movie-going and of fun of all kinds occupies a similarly questionable position - the idea is that suffering must be reduced, and if that is the sole moral good, then population control as well as an ethic of extreme austerity become ipso facto the most promising avenues for that imperative.

By contrast, MacAskill’s outlook, at least in his cash-infused Longtermist phase, is refreshingly life-affirming. Be fruitful and multiply is more or less his point. If life is good then more life must be - so the equation show - even more good. But what’s problematic about MacAskill’s way of thinking is the same general difficulty as with Ehrlich or Singer: we just don’t know what the future holds and the future, like life itself, is far too complicated to be reduced to these utilitarian best-fit solutions. Ehrlich’s hyper-confident, hyper-rational predictions ran aground on the introduction of pesticides - and the ink was barely dry on The Population Bomb before the Green Revolution rendered it obsolete. And Singer’s stringent ethical imperatives run headlong into issues of development economics - even if everybody gave to charity to the extent that he recommends, and shuts down movie-making and art and every other frivolous activity along the way, it’s not at all clear that that sort of mass charitable giving would help the people it’s supposed to help. And same goes for MacAskill. His reasoning creates a straight line where there is none. He comes to the conclusion that the good is population increase for humans and disregards any other possible ethical formulation. Setiya takes MacAskill to task over the ‘Repugnant Conclusion,’ the idea that MacAskill is endorsing a philosophical conception in which all kinds of suffering are justified simply because suffering is not really quantifiable whereas population represents a data point. But MacAskill’s reasoning gets even more ridiculous than that. On the subject of animals, he makes the eye-widening point that “If we assess the lives of wild animals as being worse than nothing on average, which I think is plausible (though uncertain) we arrive at the dizzying conclusion that from the perspective of the wild animals themselves, the enormous growth and expansion of Homo sapiens has been a good thing.” So, per MacAskill, all human life is good regardless of the degree of suffering, but animal life is situated within the domain of suffering and therefore less than good - and the extinction of wildlife is actually, from his utilitarian perspective, a net gain.

If that sounds as arbitrary as the Church Fathers ruling on whether animals have souls or not, that’s because it is - and MacAskill, with his spreadsheets and logical puzzles and passels of ‘domain experts,’ is wandering into very ancient theological territory for which science is no better of a guide than any sort of revealed religion. Hesketh, the author of the Aeon piece, is particularly good on the quasi-religious sensibilities of Big History. “The authors of Big History present their discoveries of Big History as clear moments of conversion,” he writes. “Science itself provides the mythic meaning for Big History.”

What Big History does - and this is the place where revealed religion, social justice, and dataism all converge - is to settle on a telos, some kind of eschatological direction for everything to move towards. In the case of Big History, this is done by zooming out to a scale in which individual human actions, in some iterations human history itself, come to seem inconsequential, and we view ourselves as bobbing along on a great scientific current. In the case of Longtermism, an endpoint of rational calculus is seen as the destination towards which we are all striving and everything we do is set against it. Each of those ideas fit in nicely with Baconian science and the view that technological progress and material amelioration are goods in and of themselves and the arc of world history is more or less just the endless crafting and improving of gadgets.

To get a little Old Testament about this, my own religious inclinations are a bit different. Walter Benjamin makes the helpful note that “Jews are forbidden from inquiring into the future” - a useful prohibition, flagrantly neglected by Bacon, Ehrlich, MacAskill, et al. Simply put, we have no way of knowing or even guessing what the future will be. Our ethical imperatives to ‘future people’ are laughable given how little control we have even over the present. MacAskill’s remarkable statement that the three centuries of progress since 1700 are only an appetizer for all the progress that we are likely to have over the next “millions of centuries,” and that we should plan accordingly for that impending period of time, refutes itself given, as MacAskill himself acknowledges, how “difficult” it would have been to anticipate all the changes from even a mere “three-century gap.” There is very little reason to think that we would be any better prognosticators than somebody from 1700, and the idea of anchoring our ethical apparatus to our ability to predict the future - and of a narrow segment of people predicting the future - seems so absurd as to not even permit of refutation.

In contrast to MacAskill’s oddly confident and polyannaish view of the future, the ethical imperatives, as taught in an older vein of theology, are very different - to look to oneself and to one’s community, to have humility before that which we cannot know, and to submit to our particular fate.

Fate is the critical idea that seems to have gone out of our discourse. And what fate really entails is an interweaving of an understanding of oneself with nature. In the old theological dispensation, ‘God’ basically means nature. Nature has its ingrained limits of who we are, and our ethic is to accept them and, with dignity, to abide by them. Baconian science represents the great heresy from this perspective, tearing off the veil of nature and looking to create an existence unbounded by any sense of fate. Get beyond the social justice platitudes and ethical thought-experiments and that’s what somebody like MacAskill is really advocating for - a sort of pure mathematical consciousness in which nature and fate have no meaning and the future, a future apparently of floating around in space pods, becomes the reigning theology.

All I can say is: count me out.

THE PRUDES VS SEX POSITIVITY

The prudes seem to be having a real moment. Louise Perry has a book and accompanying articles out blaming sex positivity for teaching her the wrong message about how sexual interaction actually works. Bridget Phetasy, a former columnist for Playboy, jumps in, claiming that she regrets “being a slut” and was misguided by a similar combination of feminism and sex positivity. Meanwhile, Christine Emba has called for “better rules for sex” - while insisting, contrary to most people’s experience of life, that “rules can make things more exciting.” And Michelle Goldberg, responding to Emba, claims that sex positivity got ahead of feminism and that sex positivity needs to take a breath for some extended period of time while true feminism catches up.

All of this criticism of sex positivity seems initially a little odd since, as other critics are noting, we’re in a ‘sex recession’ - and, proliferation of dating apps aside, basically nobody’s hooking up. Rob Henderson analyzes the phenomenon on ‘The House of Strauss’ and comes up with the reasonable conclusion that both things are true. The apps produce a very skewed dating market which leads to a glut of sex for a handful of users and famine for everybody else and generates all sorts of confusion - bad behavior, ghosting and entitlement, incentivized for those doing well while those who are not find themselves constantly either used or ignored.

For people who are actively in the dating market, the only possible conclusion is just to sort of tough it out - develop a thick skin, develop ‘game,’ ideally try to be a bit more ethical to the people they interact with. For those writing about this from a more theoretical perspective, painful questions come up about feminism and the way that feminism seems not actually to be aligned with some home truths of female sexuality.

And, in the space of theorizing-and-fretting, the solutions are plentiful and contradictory; and consensus seems to have been reached only on the point that what we are doing now isn’t working. Perry and Phetasy would really like to turn the clock back. The sexual revolution was a mistake, is their point. It posited sexual equality and with the corollary that women should behave like men in their sexual pursuits. But, as we’ve duly discovered, women and men experience sex very differently - and ideas of sexual conquest and sexual license have psychological repercussions for women that are simply not experienced by men. “The new sexual culture isn’t so much about the liberation of women, as so many feminists would have us believe, but the adaptation of women to the expectations of a familiar character: Don Juan, Casanova, or, more recently, Hugh Hefner,” writes Perry. “At the time, I would have told you I was ‘liberated’ even while I tried to drink away the sick feeling of rejection when my most recent hook-up didn’t call me back. The lie I told myself for decades was: I’m not in pain—I’m empowered,” writes Phetasy movingly.

That’s all a clearly valid critique of a certain peer-pressurish attitude towards sex, but the solution proposed by Perry and Phetasy is out of proportion to the problem. There was a reason the sexual revolution happened when it did - the reason being that sexual repression was at least as miserable as the bewildering openness that followed it. Read enough pre-sexual revolution literature, and it’s completely clear that no one under the old dispensation was happy. Choice was too severely curtailed, hypocrisy too heavily promoted particularly in regards to women’s sexuality. Everybody needed some freedom.

But that freedom came packaged with a set of behavioral structures - thou shalt have many partners and learn from mistakes, thou shalt, as Goldberg puts it, “be endlessly, insouciantly sexually intrepid.” And those strictures were in due course felt to be coercive. Goldberg, dealing with a critique like Perry’s, tries to separate out the strands of it - feminism must be all to the good but sex positivity is the fly in the ointment. And Goldberg, as I would expect from her, routes everything back to political banner-waving. The problem, simply, is that feminism hasn’t won enough. Once feminism prevails in the political sphere, then all of our sexual hangups will unknot themselves. “The problem is that many women are still embarrassed by their own desires, particularly when they are emotional, rather than physical,” Goldberg writes. “What passes for sex positivity is a culture of masochism disguised as hedonism. It’s what you get when you liberate sex without liberating women.

But, to me, this is almost exactly backwards. The way out of this riddle is simply to stop treating women as some kind of monolithic voting bloc. And here feminism is more problematic than sex positivity. Sex positivity isn’t really an injunction - this is where Perry, Goldberg, et al, are a bit missing the point. It’s more a set of conceptual protections for those who are sexually active - that it’s not cool to slut-shame; that learning one’s sexual desires and achieving sexual fulfillment can be a core part of the process of personal development; that there has to be an open artistic, expressive public space for honestly, unashamedly discussing sex. And sex positivity, in its matured as opposed to peer-pressureish form, is not coercive. A recent tick in the sexual revolution has been the naming of sexual categories like ‘demisexuality’ and ‘asexuality’ and these are condoned within the fabric of sex positivity - i.e. that if a person genuinely (and not as a result of sexual repression in their surroundings) concludes that they have a low sex drive then that too is understood to be an honest, healthy expression of their sexuality.

Feminism, on the other hand, has had so many different waves, each contradictory to the one before, but always with a curious insistence on the collective and on a certain conformity of thought. ‘You are a feminist if…’ seems always to be the starting-point in feminist discourse. As far as I’m concerned - and I’m aware that I don’t get a vote on this particular question - there is a wonderfully valid feminist position, which is that individual women have freedom or autonomy over how they want to live their lives. That’s it. Everything else is coercion and group-think - or, to put it most positively, is politics, coalitions assembled for specific actions. From that perspective, Perry’s anti-sex-positive advice to women - “Marriage is good,” “Hold off on having sex with a new boyfriend for at least a few months,” “Only have sex with a man if you think he would make a good father to your children” - is no more or less feminist than its rhetorical opposite, that women be “endlessly, insouciantly sexually intrepid.” What’s feminist is autonomy. What Perry is saying may well be good friendly advice but it doesn’t actually fall under any viable feminist rubric.

What all the writers discussed here have in common is a concern with messaging: what is the message that is being sent to younger women? And I understand the anxiety about it - the feeling that the messaging has been so contradictory and convoluted since the advent of the sexual revolution that nobody knows what to think. In this space, the regrets of Bridget Phetasy, a viral video by a young woman named Abby, are all very moving. But I do think, actually, that there is a very clear, very simple message that doesn’t run into the problem of contradictory advice: make up your own mind, be smart, learn from your mistakes.

That’s not very different from the messaging that’s given to young men. The point Perry makes is that sexual asymmetries are so profound that they affect everything in the society. Since women are subject to violence from men in ways that men are not subject to violence from women, it’s impossible for men and women to enter into a sexual landscape in ways that are at all similar. There’s something to that of course - and that means a whole societal apparatus designed specifically to protect women, laws on rape, sexual assault, sexual harassment, domestic violence, etc. But what all of those are intended to do is to create a protected space around women and around female sexuality so that women are able to explore their sex drives without fear of male violence and without stigmatization. Giving up on the concept of ‘sex positivity’ altogether is an overreaction and a misunderstanding of the problem. We are all sexual beings, we come to grips with our sexuality through trial-and-error - not only, as Perry suggests, “by listening to your mother.” ‘Sex positivity’ is meant simply to be a support system and venue for open communication that’s there to help people along a difficult and winding road.

Forget about Longtermism for sure! Keep it focused on the short-term and narrow-minded! Thanks for the piece.

Rock on