Dear Friends,

There are a number of new people this week. Welcome! ‘Curator’ is a regular feature I do that comes from scanning the ‘intellectual/artistic web’ and riffing off the articles that I find most interesting. Aside from the posts themselves, it’s meant to spotlight good writing around the web. At Inner Life , site co-founder Joshua Doležal discusses the numbers games stifling academia and creativity. As always, comments and arguments welcome!

Best,

Sam

WOKEISM AND BLACK SEPARATISM

This week I was talking to a non-American, who was asking me to explain wokeness — what is it? where does it come from? This is the question of the moment — just this week I’ve come across articles called ‘Why Is Woke? and ‘The Woke Whistle.’

We were talking in a very loose, unfiltered way, and what I said wasn’t about the usual suspects of Critical Race Theory or Intersectionality. Basically, what it is, I said, is that there’s been a strong stance from within the black community that any nation that could have adopted slavery and Jim Crow and segregation is fundamentally illegitimate. That the way forward isn’t some kind of incrementalist reform but a shift to a fundamentally different political entity — in other words, a revolution, a fresh start.

This has always been a powerful — and far from unreasonable — stance within the black community. What’s unusual at the moment is the degree to which it’s become accepted by white liberals, under the sort of umbrella ideology of ‘wokeness.’ For the left, wokeness yields everything. It means being on the right side of history in terms of advocating for LGBTQ and particularly trans rights; it means adopting a view of race relations that’s uncompromising, that demands a complete break from the racist past; it means a new national myth that privileges anybody who happens to be young at the moment and who will be part of a new era of atonement and repatriation; and it means a course of action that doesn’t require you to do all that much. (It’s about ‘staying woke,’ not ‘getting woke,’ there’s no longer a need, if one is left, to pretend you’ve read and understand Das Kapital, now all that’s needed is to man the Twitter feed, to be alert to any deviation from orthodoxy, to let the revolution unfold.)

I was thinking that this was a slightly more historical-than-usual perspective to take on wokeism, and I was pleasantly surprised to see John McWhorter tackling this question along the same historical scale and with greater specificity. For McWhorter, wokeism is basically the return of black separatism — and a reprise of a set of conversations occurring specifically in 1966. “There is a general sense I have always had that in 1966 something went seriously awry with what used to be called ‘The Struggle,’” writes McWhorter.

The point, claims McWhorter, is basically that ‘The Struggle’ became a victim of its own success. With the wide acceptance of civil rights, there was suddenly room for the airing of a much more radical ideology. “I suspect that much of why leading Black political ideology took such a menacing, and even impractical, turn in the late 1960s was that white America was by that time poised to hear it out,” writes McWhorter.

That turn repeats itself almost perfectly now, in the familiar array of Critical Race Theory, the 1619 Project, the school of thought of Ta-Nehisi Coates, Ibram X. Kendi, Black Lives Matter, Robin DiAngelo, etc, acting as the driving force of progressivism. “Today it has attained cross-racial influence, serving as a model for today’s extremes of wokeness, confusing acting out for action,” McWhorter writes.

It becomes important to distinguish between the different strands of wokeism. What’s mostly prevalent in progressive circles is, as McWhorter writes elsewhere, “a religion.” The emphasis is on revamping national myths, on being on the right side of history, on approaching some sort of eschatological utopia. In the parallel between 1966 and the present, though, another strand becomes more apparent, which is revolution.

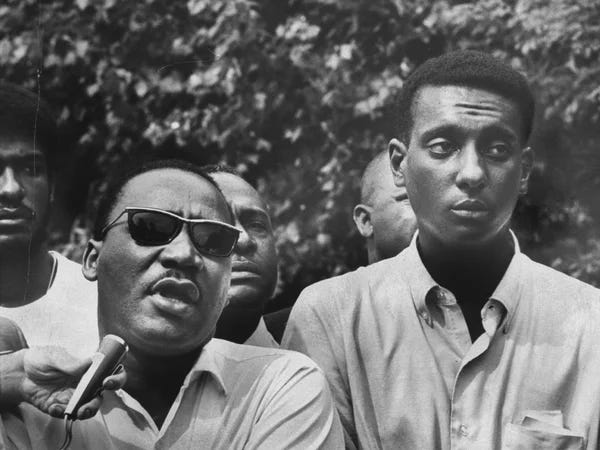

Again, the grounds for that revolution are not unreasonable. If black people had no say in the founding of the country, then the country becomes illegitimate, and what matters is the struggle for power, the birth of some new system. As Stokely Carmichael put it, and as quoted by McWhorter: “The only way we gonna stop them white men from whuppin’ us is to take over. We been saying freedom for six years and we ain’t got nothin’. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power!”

The argument with that line of thought isn’t exactly that it’s wrong but that, as McWhorter writes, it’s “impractical.” What exactly is this new system that’s going to come into being that’s better than what we have? Under whose authority does it develop? To what extent does it — as in Carmichael’s injunction — necessitate violence?

What’s so odd about the return of separatism at the moment — the vision of Carmichael and of Malcolm X — is that King’s competing vision would appear to be so triumphant. So much of the racist past really has disappeared, so many milestones have been crossed.

But, as I was saying to my friend this week, what’s so powerful about wokeism is that it brings white people into contact with excruciating truths that black people have been aware of the entire time — questions about the basic legitimacy of the American project, about the abiding inequality of the system. I find wokeism’s vision, just like Carmichael’s, to be impractical, destructive, but it is also true that it is not based on nothing — it is a grappling with a sort of unendurable knowledge.

ERNST JUNGER AND THE RIGHT’S DEATH CULT

If through McWhorter I’ve been thinking about Stokely Carmichael and the radical left, an excellent piece by Thomas Meaney on Ernst Junger is making me contend with the far right.

“Few of Jünger’s biographers have been able to resist the image of the subject as a ‘seismograph’ of the twentieth century,” writes Meaney. And that does seem to be a hard-to-resist impulse. No one had a life like Junger: a highly-decorated lieutenant on the Western Front during the First World War, then an icon of the German right throughout the ‘20s but keeping his hands surprisingly clean through the Nazi period, then dropping LSD with Albert Hoffman, becoming an icon of the ‘68 generation for his cool iconoclastic writing, and living to the age of 102 with, as far as anybody could tell, no regrets.

Of Junger’s fifty books, which seem to be, from Meaney’s account, a very mixed bag, I’ve only read Storm and Steel, his reputation-making account of World War I. It really is an astonishing book. Junger was in the thick of modern warfare — the moment when it became apocalyptic and totalizing — and found himself, on the whole, enjoying it very much. Here is one memorable description of his experience of war:

The odd thing was that the little birds in the forest seemed quite untroubled by the myriad noise. In the short intervals of firing, we could hear them singing happily or ardently to one another, if anything even inspired or encouraged by the dreadful noise on all sides.

I’d read this in the midst of several other World War I memoirs, all of them of a particular liberal tone — the idea that the war was carnage and folly, that its purpose was to show the need for ending all war. Junger had a different take. And, for him, All Quiet On The Western Front — the acme of the pacifist interpretation — was above all “a useful piece of camouflage,” distracting the outside world from resurgent German militarism.

What Junger took from the experience of war was a fascination with death, a sense that, as Meaney writes, “Proximity to death granted one privileged access to deep folds of reality otherwise hidden.” I remember reading a letter of a German soldier from Operation Barbarossa that said more or less the same thing — the idea being that humanity had looked for the truth in various guises and had finally found it in the apocalypse of the Eastern Front. Like Junger, this German soldier seemed to be thoughtful and reflective. What he was experiencing was upsetting to him, but he clearly felt — as did Junger — that it was all in the service of some kind of deeper knowledge.

In Meaney’s view, the connecting thread of Junger’s career is a loathing of the bourgeoisie. Germany was a “fortress of boredom,” he felt, “ruled by desiccated academic mandarins, while the pall of positivist science pervaded everything.” As a thread for understanding Junger, that contempt for bourgeois, comfortable living is certainly more trenchant than German patriotism — his initial impulse, in his wanderjahr period, had been to join the French Foreign Legion. The contempt held for the Weimar regime, with its soft politics, and, even, apparently, for the populist tendencies of the Nazis. “Junger’s vision,” by contrast, Meaney writes, “was of a single mass of supermen staving off the coming empire of commercial society.”

Junger is one of these people whom it is very difficult to dislike — he really was a very good writer, did everything with such an easy style — but in his lucid way what he really is describing is a death cult, the death cult that seemed to emerge out of the experience of total war in World War I and then to metastasize into Nazism. Something of that style is resurgent at the moment in Russian Fascism, in the prankster sensibility of the American far right — it’s not all grim stormtroopers, it can be good-humored and chic but that doesn’t make it any less abhorrent.

In trying to understand the inter-war period, I’ve been taken by the story of the Spanish ‘heterodox’ writer Unamuno. Unamuno was a Fascist sympathizer, with all sorts of objections to Spanish Republicans. In 1936, he appeared at a pro-Falangist event where the crowd, getting carried away, started chanting “Viva la Muerte.” At which point Unamuno broke character and said that, while his entire career he had adored paradoxes, this one was too much for him and he had to decry the movement that he had been a part of — an attack of conscience that led, in some versions, to his house arrest and death several months later.

Junger, as skilled a writer and lucid a thinker as Unamuno, apparently got to a similar fork in the road but didn’t have any of the same misgivings. Militarism, for him, was, as Meaney writes, “the alternative to both capitalism and communism: it was about schooling a society in how to consume violence instead of the cheap thrills of the market.” And the world itself becomes a “theater” in which death is a central character. If the malady of the left is collectivism — and the religiostic conformity of collectivized thought — the malady of the right is this, of which Junger serves as so helpful a guide: the death cult, the deep boredom with anything that does not partake of the aesthetics of violence.

A.O. SCOTT AND THE MEANING OF REVIEWS

A world away from Stokely Carmichael or Ernst Junger, A.O. Scott steps down as chief critic of the New York Times film section.

Scott, for me, was always the personification of good taste and stylish writing. Growing up, I had no idea of his gender and until a few seconds before writing this had no idea what his initials stood for (it’s ‘Anthony’ and ‘Oliver,’ apparently). He seemed as permanent, as venerable, as the Grey Lady herself.

After Scott, le déluge. His retirement strikes me as signaling the end of an era, in at least a couple of different directions. One, of course, is wondering what movies will look like going forward. The world that Scott inhabited, in which a vast money-making enterprise dedicated so much of its energy to pleasing bookish people like Scott, already seems like ancient history. As Scott says in his reflections on movies:

The thing I love most about the movies is their ability to obliterate reason and abolish taste. You know the jump scare is coming, but you jump anyway. You suspect you should be offended by the joke, but you laugh helplessly in spite of yourself. Why are you crying? You don’t really know, but you can’t argue with tears.

In other words, Scott’s very cerebral reviews notwithstanding, film, he came to realize, is not fundamentally an intellectual activity. It really does rest in a different part of the psyche. And this means also that film, even more than other arts, is susceptible to the manipulations coming from the AI age. It strikes me that the impact of ChatGPT and DALL-E are actually fairly minor compared to what will start to emerge from machine-learning video AI — how it becomes possible to make films with Greta Garbo opposite Tom Cruise, how anybody with access to a machine has the ability to manipulate images and develop their own films. In an art that rests, to begin with, on machines and on collaboration, that shift seems somehow more seamless than what we’re starting to experience with writing and visual art. As Scott says, “The death of cinema is almost as old as cinema itself. The End Times have a way of turning out to have been golden ages all along.” But that sounds like the voice of outdated reasonableness. My guess is that filmmaking will change even faster and more dramatically than we can predict — will become far more of an open source system; and the world in which Hollywood studios waited with bated breath for A.O. Scott’s reviews will very soon seem completely antiquated.

The other, more immediate, reflection on Scott’s retirement is about what the value is of any sort of review. Seth Rogen recently complained that “if most critics knew how much bad reviews hurt the people that made the things that they are writing about, they would second guess the way they write these things,” and that’s the impetus for a New Statesman article by Lola Seaton on reviews.

Seaton makes two claims for reviews. One is that they are democratizing; they allow the public to push back against some vaunted work of cultural authority (or, in the case of a Hollywood film, against an industrial product). “The ruthlessly critical deflation of bloated mediocrity — more a protest than an intervention after all — will always be an endangered species worth protecting,” she writes. And the other claim is that they are themselves a form of creative expression. She cites favorably Oscar Wilde’s dictum that “to a critic the work of art is simply a suggestion for a new work of his own, that need not necessarily bear any obvious resemblance to the thing it criticises.”

What Rogen seems not quite to realize — and why it’s difficult to feel sympathy for him — is that he has put himself in a privileged social position. He has been brave enough to act, to take a stage in front of a vast public. That’s admirable but it casts a shadow. It means that Rogen gets to have a life that a lot of people want to have — that a lot of people are trying very hard to have. It means also that Rogen is purporting to speak for very many people who will never get the chance to speak for themselves in the same way. That’s not to take away from Rogen or anyone else as successful — it took courage to get where he got to. But, on the other hand, in being willing to ‘take space’ in the way that he did, he made an intrinsic deal that he would expose himself to public scrutiny in whatever form it took — and that’s the deal that Rogen, with very bad grace, is having second thoughts about now. If you purport to speak for other people — and that’s what a film really is — then you have to be willing to endure their critique of the job you do.

That being said, I do understand where Rogen is coming from. Reviews can be smug and snarky with very little idea of the effort that went into creating the artwork that’s being so blithely ripped apart. And, in a way, Scott’s retirement marks the end of a particular era — in which a movie is seen as being made in a vacuum, with very little acknowledgement of the business or the mechanics behind it, in which it’s possible to play a charade that a film is some modest offering subject to the discernment of a writer like Scott. Scott was such a classy, intelligent writer that he could pull it off, but, really, this mode of reviewing was far from optimal.

As Scott himself says of his credentials at the time he got the Times job, “I was a freelance book critic and youngish father of two small children. I had seen a lot of movies and reviewed none of them. I was very puzzled about my sudden career swerve.” And, actually, that is a problem. There’s some idea in reviewing — Seaton takes this same perspective — that the reviewer should be as blissfully ignorant as possible of how the sausage is made, should come to the work with completely fresh eyes. Seaton quotes the writer Adam Mars-Jones as saying that he does his best to pretend the book he is reviewing “arrived not by my letter-box but through a portal from an alternative universe.”

But I’ve noticed that — with rare exceptions like Scott — I find myself having almost no interest in reviews written by people who haven’t done similar work themselves: in book reviewers who haven’t written novels, in film reviewers who haven’t worked in the industry. The process of making anything is so tangled, so laborious, and people who haven’t done it themselves often have no idea of what is really involved. Serious writers, I’ve noticed — I’m thinking of people like J.M. Coetzee, Milan Kundera, Nicholson Baker, who are also wonderful book reviewers — tend to be much gentler, much more understanding than the trade reviewers. This does not mean that they are not also harsh — but the harshness takes a different form. They are not consumers, waiting with arms crossed, for something to entertain them or be worth their while. It is as if they are sitting over the shoulder of the person making the work — are aware of what the artist is trying to do, applaud them for what they do accomplish, and gently remonstrate with them when their project isn’t worthy of their talents or when (as very often happens) they get scared and pull up short from what they really want to say. Reviewers who are also writers (or filmmakers) are a very different breed from the trades. They are on the side of the artists, they get that it really is hard work, but that doesn’t result in flummery or social promotion — they understand that art is an endlessly difficult activity and anybody bold enough to really do it wants the truth of how they’re doing, wants to be pushed to excellence.

BEWARE OF MICROCHIPS

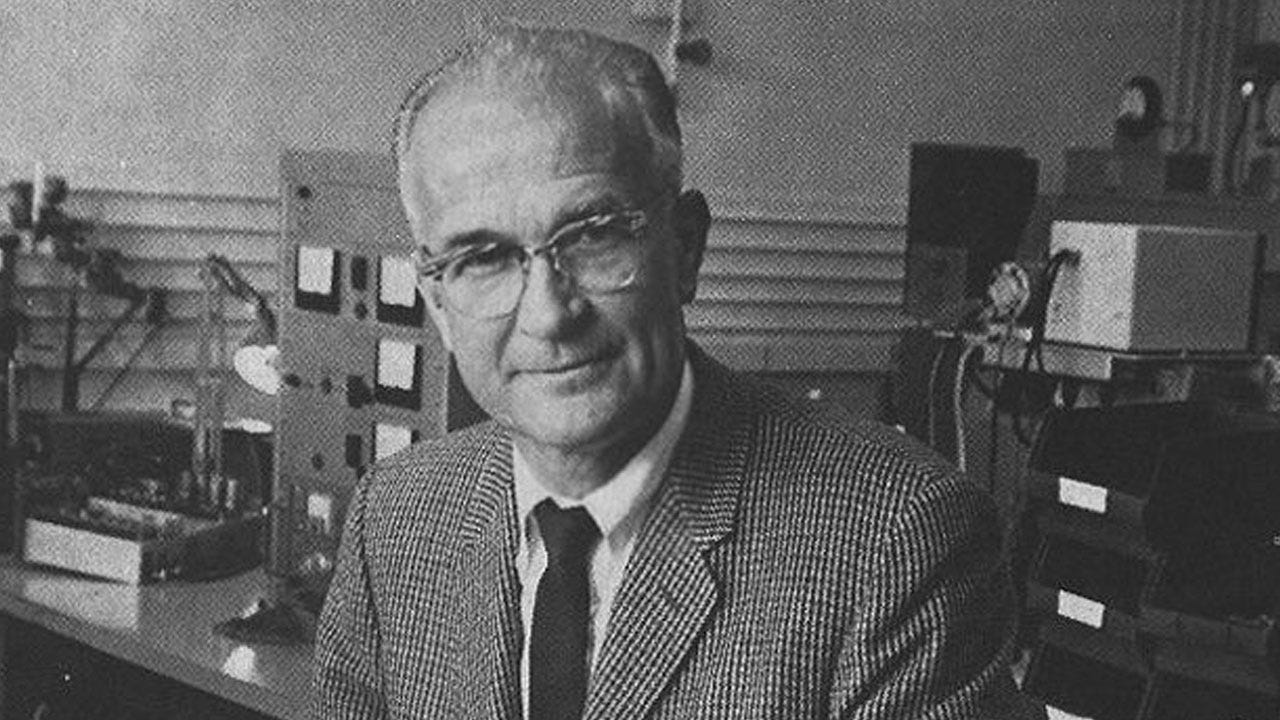

In ‘Commentator’ this week, I wrote about the new Cold War — and, via David Brooks’ discussion of Chris Miller’s Chip War, the entanglement of chip technology and high-stakes geopolitics. In The London Review of Books, the professional polymath John Lanchester writes at greater length riffing off of the same book. The 21st century world, he writes, is really the world of microchip processing — and that means that it’s the world of a single inventor, William Shockley, who, Lanchester notes, was a “horrible person”; and that means that it’s the world of a single industrial process, the development of microchips for the war effort in Vietnam and then on the civilian side through Silicon Valley; and that means that it’s the world really of a single factory, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s Fab 18 in Tainan City, the only place that makes advanced microchips to scale.

The lesson from all this is that the purported tech democratization of the last half-century is not really quite so deep as it seems. It rests on hardware, and that hardware continues to be governed by geopolitics. As Lanchester writes, “Chips are ubiquitous, but top-end chips are not: they are the product of a highly concentrated manufacturing process in which a tiny number of companies constitute an impassable global choke point.”

And with the advent of the new Cold War, the first move is to secure the most precious asset — protect Taiwan and limit the sale of microchips to China. Lanchester writes, “Trump talked a good game about trade war with China, but when it comes to intentionally damaging China’s strategic interest, nothing he did was within a country mile of Biden’s CHIPS Act.”

The point here is that the CHIPS Act — “with little notice before and not enough attention afterwards” — may well have been the defining event of our era, the moment when the U.S. really ended its thirty-year concord with China and shifted to an intense industrial if not military rivalry. We tend to make the mistake of thinking that the ‘military-industrial complex’ was a World War II and Vietnam-era phenomenon. It wasn’t. Apparent democratization notwithstanding, advanced tech remains intricately interwoven with national security and its machinations. It wouldn’t be so surprising if, in the cyber age, the turn towards conflict with China started, really, with microchips.

Appreciate your clear-eyed take on wokeness, wokeism, whatever it is. As you say, that view typically yields everything, intellectually. There is no conversation -- simply a rehearsed consensus. This is what leads AA-style exercises, such as going around a circle and saying, "I'm so-and-so, and I'm a racist."

Where I disagree slightly is the notion that it doesn't require anyone to do anything. "Doing the work" is very much part of Robin DiAngelo's regimen. There are books to read, workbooks to complete. What I find paralyzing about the movement, however, is how risky engagement is. See this recent blog post, for instance: https://tzedeksocialjusticefund.org/white-women-doing-white-supremacy-in-nonprofit-culture/. Doing too much work too publicly, yielding the argument too unreservedly leads to charges of white saviorism. I found this paradox quite distressing as a professor and really wrestled with it as a department chair when there are calls for public statements committing to anti-racism.

To the Stokey Carmichael example of radicalism being emboldened by a more accepting climate I might add Jamaica Kincaid's "A Letter to Robinson Crusoe," which somehow made it into the Best American Essays 2020: https://books.substack.com/p/diary-a-letter-to-robinson-crusoe. The critique of colonialism, as you say, has a point. It's the turn toward dismissing the entire Enlightenment and glorifying a pre-industrial paradise that is jaw-dropping. I realize I can get off in the weeds about Ibram Kendi, but it's just this kind of logic that often baffles me in his writing.

This was a fantastic read. Where to start really...I’m particularly struck by Junger. I haven’t read much about WWI. WWII took that place of wartime fascination. But I haven’t read a memoir that wasn’t, as you put it, of a liberal bent. Pacifist to the core. Which is a blind spot to the spectrum of human experience on my part.

His mention of birds singing as the battle rages on reminded me of a paragraph from a Holocaust survivor’s memoir (whether Gerda Weissmann Klein or Elie Wiesel, I can’t remember). They are on a march, leaving the death camp as the Allies close in. And when they look up they see trees. Notice the sky. That the natural world is as it was before and will be after, even in the midst of hell on earth.

Such a stark contrast...I will have to read his work to get the full scope of it. Thank you for writing!