Open Marriages: Jean Garnett v. Percy Shelley

I have this fantasy that, somewhere in the dawn of time, let’s say the year 1500 BCE somewhere around Varanasi, the first edition of The Ethical Slut was published and it created so much chaos, so much confusion around ‘primaries’ and ‘side pieces’ and ‘open relationships’ that the sages all got together and decreed arranged marriages, strict monogamy from that point forward. And, now, the genie is out of the bottle again and nobody is quite sure what to do with it.

Browsing around the sort of literary-and-lifestyle web this week I’ve come across two pieces on open marriages, one that I’d say is opposed, one that I’d say is in favor – but who the hell knows, the point is that it’s such a difficult topic that nobody can really get a handle on it, nobody seems able to convincingly, honestly, say whether it has worked for them over an extended period of time, let alone answer for their partner.

The article more or less in favor of open marriages is by Jean Garnett in The Paris Review. It’s beautifully written, if somewhat overwrought. The story Garnett tells is pretty straightforward. Six months after her daughter was born, her husband “calmly set the idea on the table, like a decorative gun.” And then she and her husband pass through various stages in the opening of the relationship – like stations in an initiatory rite. There’s the research phase, which leads Garnett to the ur-text of modern polyamory, Nena and George O’Neill’s 1972 Open Marriage: A New Lifestyle for Couples; the sharing phase in which Garnett finds herself to be the cool girl at a gathering of married people who already – everybody is in their 30s – are mourning the end of their sex lives; the phase in which her husband slides into her bed and tells her he had a ‘fun’ night out and it seems to be no more complicated than that; the jealousy phase, in which Garnett is thrown off-kilter by discovering a new playlist on her husband’s Spotify account and has to grapple with the intrusion of other people into her domestic life; the phase in which, thanks to the ‘totemic power of random dick,’ Garnett finds herself becoming more closer, more sexually connected to her husband; a truly complicated phase in which her husband clearly develops feelings for somebody else and they all become friends, Garnett reaching a pitch of urbane sophistication by thinking “My husband has great taste in women”; then a sort of archipelago phase in which both Garnett and her husband both branch out, their connection with each other becomes a bit shallower and more formal, they have whole lives occurring outside of the domain of their relationship and the relationship is where they kind of come to touch base before venturing out again. “Marriage might be the ideal place to process a bad sexual encounter with somebody else,” writes Garnett, bidding for an even higher pitch of urbane sophistication.

It sounds cool and classy, like a certain kind of New Wave movie, but I don’t quite buy it. In a way, the difficulty for me is Garnett’s prose itself. She’s so aware of how everything comes off, so into the casual shock of a tossed-off line like “the six-and-a-half-pound human body pulled out of the place I get fucked, or one of the places” that her psychology starts to feel almost entirely performative, as if everything is calibrated for the New Wave-ish scene of the stylish, archipelagoed life, or, for that matter, for The Paris Review article that she will write about it once she reaches the happy, ultra-mature end. There’s something a little suspicious about the way that the husband as an autonomous actor gradually disappears over the course of the piece. There’s a great deal about her babysitter, for some reason, a certain fascination with each of the husband’s succession of new girlfriends, and then an image of the “familiar baseball hat pulled low over the messy curls” glimpsed on a moving train. How conscious is Garnett being here? The moving train, his gradual disappearance, makes it feel as if he’s turned into a stranger for her – maybe a broader phenomenon of which the opening of the relationship is only a symptom. A certain lack of self-consciousness appears too in Garnett’s not discussing, within the article, her reasons for writing the piece or her husband’s reaction to the idea – since the article would inevitably be an enormous disruption in the delicate balance that, she writes, they have found for themselves.

The overriding feeling is that Garnett just isn’t quite as mature as she thinks she is. A passage, tacked on as a kind of appendix to the jealousy phase, describes the feminist ramifications of agreeing to an open marriage. “I did and do worry, especially about the younger girls, in their twenties. Were they all right, these kids? How did they feel about being ‘on the side’? Occasionally I stumbled into something like outrage on their behalf, as though I were the spirited friend in their drama: ‘Fuck that guy!’ Weren’t they being exploited? In fact, wasn’t I exploiting them, outsourcing the labor of care, pleasure, attention, affirmation to this scattered precarious workforce? What was troubling me most, I suspected, was that among the squatting archetypes I’d been discovering in myself was the complacently cucked wife, shoring up the patriarchy for her own convenience.”

I can just picture being in an acting class, hearing somebody deliver that monologue and having the teacher dig away at the false consciousness of it. Is that really what Garnett is feeling on the nights when her husband is out on a date – she is concerned, as a feminist, for the well-being of the younger women her husband is sleeping with? And I can imagine, bit by bit, a skilled acting teacher scraping away to what Garnett is actually feeling, which may be more messy and raw than can comfortably sit in The Paris Review.

Garnett isn’t the first writer to be guilty of a certain prettification of the concept of open relationships. The New Statesman has a cute piece about Percy Shelley and the havoc he wreaked on his social circle with his doctrine of free love. Within a two month period in 1816, two women close to him committed suicide – his first wife Harriet, whom he had left for Mary Godwin; and Mary’s half-sister Fanny Imlay, who was also in love with Shelley. “Loving Shelley was lethal because Shelley idealized love,” editorializes Frances Wilson, the author of The New Statesman’s piece. Although, actually, writes Wilson, it was more that havoc was wreaked on Shelley’s psyche by Mary Godwin’s father and his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, which was the racy book of the time, the Georgian answer to Open Marriage or The Ethical Slut. Shelley took the doctrine of free love very seriously – “Love withers under constraint,” he wrote in his notes to Queen Mab, “love is free: to promise for ever to love the same woman is not less absurd than to promise to believe the same creed” – and he abided by it, which is more than could be said for Godwin père, who forgot all about free love and everything he'd written in Enquiry Concerning Political Justice the moment Shelley ran off with his daughter. Editorializing again, Wilson claims that it may have been the best for all concerned that Shelley drowned at age 29 – that Mary was already miserable with him and went on to have “more peace as a widow than as a wife.”

So in the Garnetts versus the Shelleys, there’s one point for and one point against open marriages. In a sense, though, the framing of the debate as open marriages as opposed to monogamy is missing the point. It’s really about ethical, transparent cheating as opposed to covert cheating, which was always part-and-parcel of the monogamous framework – and neither one is exactly ideal: there is, almost certainly, no good way to cheat. Some of the more optimistic accounts from the far shore of polyamory claim that it’s possible to live without jealousy – “I don’t have many jealousy triggers,” says Kevin Patterson, coolest interviewee in Susan Dominus’ New York Times Magazine piece on open relationships, “but I don’t like it when someone my wife is seeing takes the parking spot in front of my house” – but, in the more typical narratives, jealousy is a more difficult force to contend with than anyone anticipates, as was messily discovered in the social circle of the Shelleys. The seriously polyamorous, as explored in Dominus’ piece, behave like adepts in the art of jealousy, allowing jealousy to show itself and examining all of its facets, what it reveals about the deeper insecurities underlying the relationship.

In other words, it’s the ethical aspect of ENM that’s most challenging. People have had varieties of open relationships and arrangements for a tremendously long time – and, for the most part, probably, have treated each other badly and then have either picked up the pieces or not. The notion of ethical cheating seems to align with periods of extraordinary idealism – Godwin’s Enquiry Concerning Political Justice appeared in 1793, Open Marriage: A New Lifestyle For Couples in 1972, and the wave of The Ethical Slut, Dan Savage, Sex at Dawn, etc accompanies a certain millennial buoyancy, a feeling that the open web, the co-ed society, a kind of gentle hipster lifestyle can create a more enlightened sexuality. The belief that follows from idealism is that people are capable of taking vast ethical responsibilities onto themselves, avoiding strictures, avoiding institutions, figuring out their own morality. That was a tall order for the Godwins and Shelleys, as I suspect it may be for the Garnetts, essentially for just about everybody other than the high priests of polyamory whom Dominus depicts, who treat cheating as essentially a spiritual exercise, an opportunity to examine the deepest, most unpleasant parts of themselves and of one another. “Daniel and Elizbeth had turned their union into an elaborate puzzle,” Dominus writes of the star couple in her piece, “one they could only solve together, had to solve together, for the well-being of their family, even if doing so demanded more from each of them than their marriage ever had.”

Incel Sociology: Mary Gatiskill vs the Righteous Mob

I really don’t mean for this section to turn into a Mary Gaitskill fan letter, but what can I do – she really is the best, and in my scrolling through so many Substacks and posts there’s just very little, really, that compares to her cool intelligence and to her ability to write eloquently and impassionedly from a place of not-knowing.

As subject matter, incels is right in her wheelhouse - a topic that generates nothing but judgmental aversion from people who know nothing about it and that, as Gaitskill understands, can be dealt with in a more human, compassionate mode.

Gaitskill’s piece is a nice rebuttal to Amia Srinivasan’s article The Right to Sex, which drove me crazy ever since I first read it. Srinivasan starts with the alpha and omega of rhetorical straw men, Elliott Rodger’s pre-massacre manifesto, which is taken to stand in as a kind of declaration or collective subconscious for the incel movement. Having established the philosophical link between murderousness and identifying as incel - and Srinivasan would be the one to know, she is a chair of philosophy at Oxford - Srinivasan proceeds to break down the fundamental premise of the incel community, the idea that its members have a right to sex at all. It’s odd to use the language of rights to discuss behaviors, but Srinivasan’s academic specialty is rights and, in a kind of extramural, popular journal like the TLS, she can indulge in an extension of the logic of rights. And from that vantage-point, since rights are mostly about individual autonomy and sex involves crossing into the autonomy of somebody else, then, case closed, incels have no right to sex and they should go back to where they came from and, ideally, try not to murder anyone.

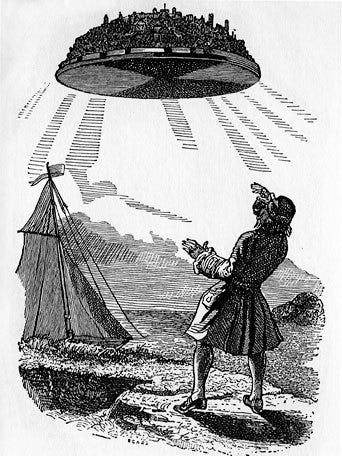

This feels like Gulliver’s visit to Balnibarbi, the land ruled from the rock-throwing castle in the sky, but in the widespread discussion that followed Srinivasan’s article nobody seemed to notice just how inappropriate the tools she was using were to the job at hand. Gaitskill - a fiction writer, not an analytic philosopher - brings the discussion back to where it belongs, in human behavior and human pain. “The idea that there are thousands of people (men; men are people) who feel so utterly despised and rejected on the most intimate level makes me feel incoherent pain that is oddly both glancing and deep,” writes Gaitskill. “That they react to their feelings of being despised by acting the part makes me sick, like screaming inside sick.”

The analogy is inevitable to the state of American high schools in the ‘90s before Columbine - the initial assumption (which turned out to be largely untrue) that Columbine was the work of the ‘Trench Coat Mafia,’ that bullying and hierarchies were so intense in high schools that at some point the nerds would get fed up and try to violently turn the tables. And the reaction to that was, apart from some surface efforts to soften social hierarchies, a deep suspicion of the nerds - ‘school shooter’ was a new epithet that could be applied to lonely kids who didn’t fit in. And same goes for incel, which is now taken to be a prelude to violence in the way that Goth was at the end of the ’90s. Yes, there have been horrific cases of violence that seem to be driven by incel reasoning and facilitated by chat on incel forums. The shootings by Rodger, Alex Minasian, Scott Beierle, etc, point to a dangerous pattern, but it’s a very odd and cruel response for the society as a whole to go to war against involuntary celibates, just as it was odd and cruel after Columbine for the media to, in essence, go to war against high school losers.

Gaitskill is probably right to leave this topic in a state of confusion and aporia. “I don’t know why I have such a complex reaction to this but I do,” she writes. But she dismisses the intel mentality by saying that it’s ‘painfully unimaginative.’ Probably what that means is she’s encountering the Elliott Roger-style racism and Pickup Artist logic that seems to be such a staple of the incel world. And I think that if I spent time on incel forums, I might find it similarly repelling, its weirdly un-updated versions of 19th century phrenology and racial theory, the complete inability (this may be above all what Gaitskill means by unimaginative) to think beyond status hierarchies.

But there is something, it must be said, to incel sociology, at least as it’s filtered to me through Gaitskill and an engrossing New York Magazine article on the phenomenon. The real issue, claim the incels, is the breakdown of monogamy and the family structure. Even in the framework of socially-mandated marriage, it was never so easy to be hopelessly unattractive, but if every Jack had his Jill, and maybe above all if romantic relationships were dictated by class, then life wasn’t so bad for the incel progenitors. (Probably best of all for the incel was the society of arranged marriages.) But the open sexual marketplace obliterated that degree of protection. What’s come in the place of the old model is more freeing in all sorts of famous ways, but it is also ruthlessly hierarchical and status-oriented - and anybody who has doubts about that should open a Tinder account. As far as I can tell, the sexual marketplace almost perfectly mirrors the neoliberal marketplace in general - rampant inequality, a strict division of winners and losers. Male incels aren’t the only ones who are disenfranchised by the system - but they are the most vocal and restive about it.

So what’s to be done? Well, nothing on the level of public discourse. Nobody’s getting rid of Tinder. Srinivasan’s neatly-philosophical solution of rescinding the ‘right to sex’ from those who haven’t, I guess, earned it is both mean-spirited and comes from a domain of norms that has nothing to do with real-world behavior in the sexual marketplace. To talk about the repercussions involved in the dismantling of the old structures of monogamy and the family unit involves thinking on the level of individual feelings and psychology - thinking more like a novelist than a philosopher. In a status-dominated sexual marketplace there are winners and losers. That sucks for anybody who loses out - and it shouldn’t be too much of a surprise that some of the people who lose out are angry and are incoherent in their anger. “If I was, say, 25 years old and had never experienced sex and tenderness I too would be in a very ugly mood,” writes Gaitskill. For the society-at-large to tell those people some variation of that it’s all in their heads or that they’re not entitled to their own pain or anger strikes me as cruel and unusual. Pain is pain. It ends up being expressed one way or another. And Gaitskill is right to just try to listen to it, think about where it’s coming from, before brandishing the pitchforks.

Fascinating read. My parents had a 5 year open marriage and it was less a “prettification” of sex and more pure survival. I wrote about it here: https://unfixed.substack.com/p/chapter-5

Thank you for liking and thinking in-depth about my incel piece. I appreciate that but, even if you hadn't mentioned it I would really like this piece. Its so thoughtful and real which, as M. Van Slyke noted, is vanishingly rare.