Commentator

Rushdie Stabbing, Tinder Anniversary, Nuclear Enthusiasm, Psychedelic Athletes

THE RUSHDIE RESPONSE

I was going to skip writing about the Rushdie stabbing because I felt that the event spoke for itself - and that any commentary on it was just an attempt to spin a senseless, terroristic act along the lines of whatever perspective one happens to have on the current culture war.

But the response has been so ludicrously predictable and polarized that that seems to call for its own commentary. The mainstream liberal publications have been very slow to use the ‘f’ word and have been insistent that whatever the reasons may be for the stabbing, it is categorically not any clash of values between Islam and the West. One NY Times article seemed to imply that it was a case of anti-Muslim bigotry conducted by Muslims - like an internalized extension of the usual suspect of Western racism and imperialism. Meanwhile, the right has of course concluded that it is a clash of values between Islam and the West - and that, probably, Islam deserves to be canceled. And the sort of militant center - like in Bari Weiss’ essay on the stabbing, which is the jumping-off-point for this post - sees the whole episode as an Alamo for freedom of expression, proof that the forces of censorship are not just repressive but violent and that the only possible honorable action is courageous speech.

That’s basically my position but with a few caveats. In terms of the Rushdie stabbing, my initial reaction had been that it was like one of these frozen conflicts come back to life - it seemed like the community of the faithful hadn’t taken the fatwa as much to heart as everybody had initially anticipated and had gradually lost interest. That eventually became Rushdie’s attitude as well. And it was news to me to realize just how much devastation had actually been carried out as a result of the fatwa: the Japanese and Italian translators of The Satanic Verses stabbed, the Norwegian publisher shot, the Turkish translator the victim of an arson attack, bookstores firebombed in the U.S., and riots breaking out in Mumbai and Islamabad.

As it turns out, Rushdie’s heroism and freedom of expression is something of a secondary event, compared to that of everybody who worked on or sold The Satanic Verses and never had the benefit of additional security and had to make excruciating decisions about exactly how much ‘freedom of expression’ mattered to them. As Andy Ross, the owner of one of the firebombed bookstores, wrote: “It was pretty easy for Norman Mailer and Susan Sontag to talk about risking their lives in support of an idea. After all they lived fairly high up in New York apartment buildings. It was quite another thing to be a retailer featuring the book at street level. I had to make some really hard decisions about balancing our commitment to freedom of speech against the real threat to the lives of our employees.”

So it’s important with something like this to be clear about what we are actually standing for - what the values are that’s made sales clerks and translators the target of terrorists.

It’s not exactly freedom of expression or freedom from censorship. Censorship is an almost meaningless term within the publishing world because the entire industry exists as sort of an elaborate apparatus of censorship: far more expression is curtailed and ‘rejected’ than will ever see the light of day. The publishing industry never exactly militates for free speech. It chooses between different kinds of speech and tends to choose whatever is most inflammatory (or to be more precise, aims to choose whatever is most inflammatory without inviting blowback on itself).

And the value at stake is also not that writing does no harm. All writing is cruel - all writing has an element of possession in it with a certain emotional violence a close corollary. An oddity of the press’ response to the Rushdie stabbing has been an insistence that writing and violence are completely separate domains. “Words are not violence. Violence is violence,” writes Weiss. Thomas Chatterton Williams writes the exact same thing on Twitter. “Literature exists in the realm of the hypothetical, the suppositional, the improbable, the imaginary,” writes Adam Gopnik. “The idea that words are equal to actions reflects the most primitive form of word magic, and has the same relation to the actual philosophy of language that astrology has to astronomy.”

I actually don’t think that that’s true. The sticks and stones thing was never very convincing as a nursery rhyme and it’s odd to see adults quote it as fact, as Gopnik does. Writing moves into the domain of politics and of violence all the time in the form of political manifestos and so forth. ‘Softer’ forms like journalism are often based on an elaborate system of pillorying the subject who has naively agreed to participate. Janet Malcolm, in particular, is convincing on this topic. And fiction isn’t really in some secluded garden of art for art’s sake - fiction is fully capable of stepping boldly and recklessly into the political realm.

And the protestations of literature’s eternal innocence are a bit insincere. Rushdie knew full well what he was doing when he wrote and published The Satanic Verses. And other writers - none of them exactly soft-pedalers in their own work - criticized him harshly. In 1989, John Berger wrote: “I suspect that Salman Rushdie, if he is not caught in a chain of events of which he has completely lost control, might, by now, be ready to consider asking his world publishers to stop producing more or new editions of The Satanic Verses, not because of the threat of his own life, but because of the threat to the lives of those who are innocent of either writing or reading the book.” Roald Dahl wrote: “Rushdie must have been totally aware of the deep and violent feelings his book would stir up among devout Muslims. In other words, he knew exactly what he was doing and cannot plead otherwise. This kind of sensationalism does indeed get an indifferent book on to the top of the best-seller list — but to my mind it is a cheap way of doing it.”

The point was that it’s not as if freedom to express is always in the right and censoriousness is always in the wrong. Sometimes writers do miss the mark morally. Sometimes they do create more pain than can possibly be compensated for by the value of their work. The act of writing is always an intricate moral act, and writers and publishers really do have to consult closely with their conscience for every piece of writing they disseminate. And Dahl may well be right in Rushdie’s case - that he was to some extent engaged in a bit of showmanship, that he didn’t think it all through clearly enough. But, in any case, that’s his business. That’s a very difficult moral decision that Rushdie made that he - and everybody involved with The Satanic Verses - has had to live with for the last thirty years.

The tendency of a critic like Weiss, and of Rushdie himself, is to frame everything in terms of values. There is a core Western tradition, runs that line of thought, that creates a protected circle around expression, that eschews violence within the domain of speech, that values freedom above all else. It was clearly a significant decision within Rushdie’s life to participate in that framework. If writers from Western countries are able to write freely and critically about Christian subject matter then he should be able to do the same about Islam, went that reasoning. And, in Rushdie’s articulation of the issue, it absolutely is all about cultural fault-lines, the values of ‘the West’ standing for a certain prioritization of individual freedom.

But what’s important to understand there is that that kind of freedom doesn’t exist as a society-wide dictum, as some sort of mission statement that everybody references when they’re not sure how to behave. It involves genuine individual freedom - which means a strenuous wrestling with one’s own conscience; and every individual managing that task in their own way. Pamela Paul, who was working in a bookstore at the time of The Satanic Verses’ release, recounts that “many of my fellow employees may have not wanted to have anything to do with it.” WHSmith pulled The Satanic Verses from a couple of its stores in the wake of a series of attacks. And that may be cowardly but it’s also understandable. Everybody chooses their own values and it’s a reasonable thing to not want one’s store to be firebombed for the sake of a single title.

But for those who kept coming to work, for everybody in the industry who stuck with Rushdie, and for Rushdie himself, a very clear, strong value was articulated - that courage and freedom of expression were more important than anything else. Again, there’s no reason why that should be anybody’s value - it may not even be a very good value - but when The Satanic Verses received the vitriol that it did, those espousing that value looked deep within themselves, decided that The Satanic Verses, whatever the merit of the book itself, had become a symbol of courageous self-expression.

As Andy Ross recounted of his moment-of-truth in 1989:

“So we took a vote [in the aftermath of the firebombing]. The staff voted unanimously to keep carrying the book. Tears still come to my eyes when I think of this. It was the defining moment in my 35 years of bookselling. It was the moment when I realized that bookselling was a dangerous and subversive vocation. I didn’t particularly feel comfortable about being a hero and putting other people’s lives in danger. I didn’t know at that moment whether this was an act of courage or foolhardiness. But from the clarity of hindsight, I would have to say it was the proudest day of my life.”

That’s the lesson here. Literature can be violent and it can hurt. It is not an unalloyed good - just as courage is never an unalloyed good. But, as Ross and his staff realized, there is something in literature that is worth fighting for even at real cost to oneself.

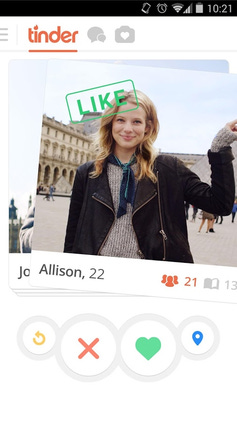

TINDER TURNS TEN

Tinder just had its tenth anniversary - the surprise here being not, wow, Tinder is ten already but that our entire way of thinking about dating got completely shaken up in that relatively short time period. To celebrate the milestone, New York Magazine recruited salty Tinder veteran Allison P. Davis to recount all of her war stories on the app. As she grimacingly points out, “The longest-term relationship I’ve had from Tinder is with Tinder itself.” And she really did go through a lot on the app - and is willing to share everything about the experience. Most interesting, I suppose, is the gradual shift from buoyant enthusiasm about meeting new people to, in the end, a principle of do no harm, making her profile blurb things like “please don’t catfish me” and “if you voted for Trump swipe on.” The various pit stops along the way are interesting as well - her ever-shifting theories of romance, a sly early-2010s theory that dating “is all a numbers game” to a mid-2010s careerist sensibility that, for Tinder to work, she would have to treat it essentially as ‘a second job’ to, eventually, a Russian roulette approach, inviting a strange man directly over to her apartment, no date first, but with the light precaution of forwarding his photo to friends in case they needed to aid the police in retrieving her body and putting out the APB.

Davis’ piece, while pretty comprehensive to her own experience, skips over virtually all of the major points as to how Tinder (and its rival apps) have changed the landscape.

1.With dating apps, a certain murkiness goes out of sexuality. If in the days of yore pre-2012, sex was all about ambiguity - an interaction in a public place, at a party, at work, leading to something often with the parties initially knowing nothing about, or lying about, one another’s status, and with a dating profile, say in a newspaper, understood to be an absolutely last-ditch sign of desperation - sex in the Tinder era lends itself to intentionality. Everybody on an app at some moment chooses to be there and has to define who they are and what they are looking for. I am idealistic enough to still believe - although without a ton of evidence backing this - that that has to be a good thing (there has to be some recent social development that’s been positive, right?). And I think there is some sense that public space has been cleaned up as a result of so much of sexuality moving onto the apps - that there is more room for interaction between people of the opposite sex IRL that is not all an elaborate pickup. The word ‘ethical’ shows up in discussions about dating in a way that it didn’t ten years ago. People seem to spend more time thinking about and articulating their ‘boundaries.’

2.On the other hand, if sexuality shifts to being intentional it also becomes an addiction. Davis puts it nicely by saying that her relationship is with the app, and everybody she meets from it, even if they are real people, come to seem like a function of the app. “If you don’t like somebody you just send them back to the Internet,” a friend told me recently of her experience with the app. “They weren’t people to me,” writes Davis of the avatars she is messaging with. Sexuality turns into something very different from how it’s imagined in a relationship or romantic model - very different from any kind of model other than raw evolutionary biology. It just turns into swiping, a brutally direct mating dance in which everybody attempts to select the partners they find the most attractive and are selected in turn by the prospective partners who find them attractive and somewhere in there is optimization. After however many millennia of poetry and romance, it’s like the crudest possible way of thinking about love - and it’s come to occupy a place in the society from which there’s no real alternative for anybody looking to date and which is experienced only as an addiction.

3.In the old way of doing this, sexuality was all about socialization - going to parties one didn’t really want to go to, spending time in bars, hanging out with friends one didn’t really like in the off-chance of meeting someone. With the apps, sexuality becomes all about loneliness - it’s ‘bowling alone’ taken to the extreme. It’s important for a person to be unattached - that’s a precondition of dating - and then the process of courting occurs almost entirely while one is by oneself. That fits in with the broader trend that’s been heightened during the pandemic, the shift out of the office, and into the home. There’s no going out, as there used to be, with the premise of some sort of happy accident, some unexpected surprise, occurring. The new regimen is to reach out to people outside one’s circle solely if one needs a specific service: business or sex or love. “Tinder was now just Seamless for sex,” writes Davis with admirable clarity.

4.At the same time this sense of egalitarianism should be what’s most exciting about the new regimen. It’s perfectly possible now - I think it’s common - to have couples live together or get married without having had a single Facebook friend in common from before they met. In the old world, dating was highly institutional - depended on where you worked or went to school or whether you had friend groups overlapping with a prospective partner. The dating apps present the possibility of tearing all that apart, of dating entirely without regard to social status.

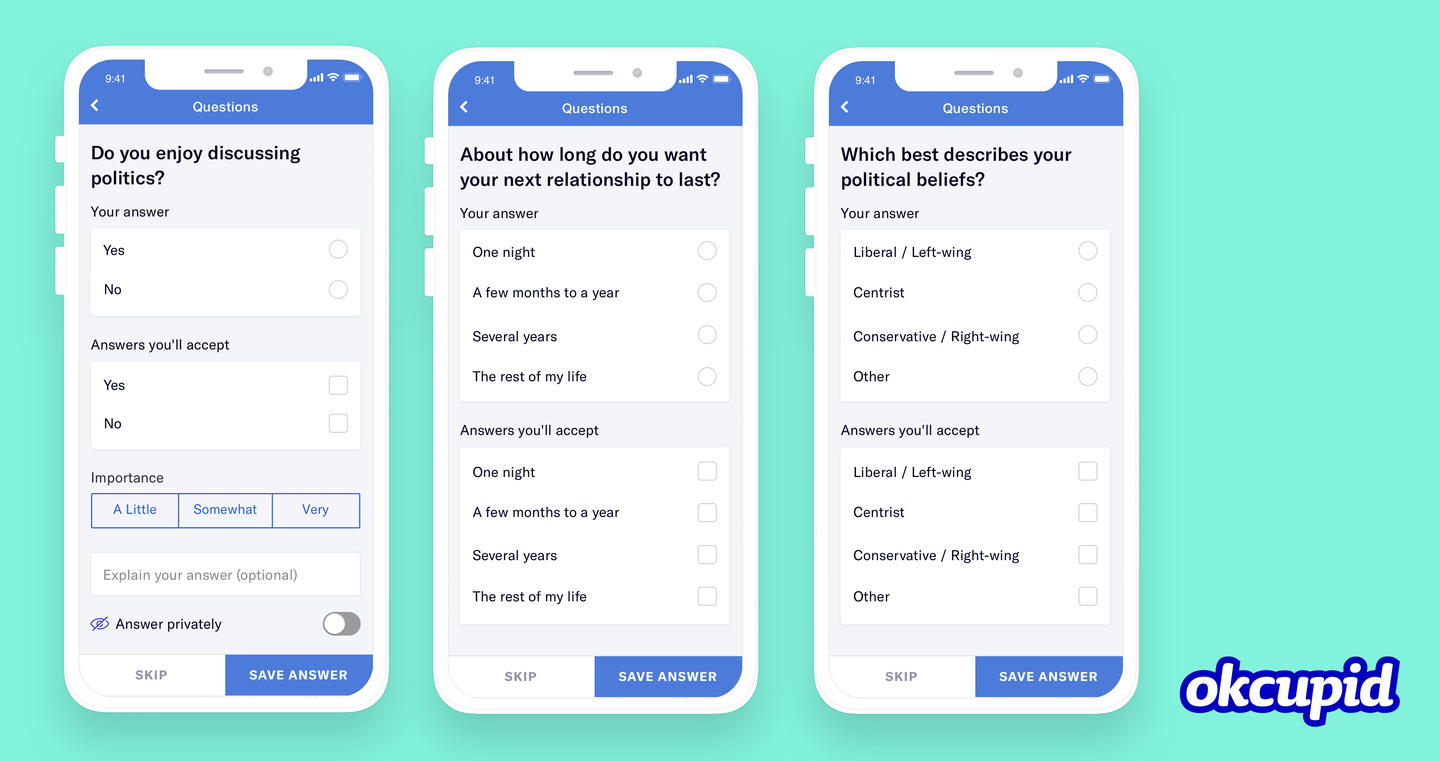

5.That should be a thrilling, highly romantic development, an entire society of Cinderellas, of people meeting through shared affinity regardless of social status. But instead of that, of course, we have engineered a society that’s more ruthlessly status-driven than probably just about anything that’s ever existed. On the apps you instantly and incontrovertibly know your worth in the sexual marketplace. An earlier generation of dating apps, OKCupid most prominently, attempted to recreate some facsimile of real-world matchmaking with all the intrusive questions, the bid to align couples through shared interests, qualities, backgrounds, etc. Tinder blew all those apps away by being perfectly, uninhibitedly shallow - the principle of ‘Hot Or Not’ taking over the entire dating marketplace. What Tinder seems to be above all - and it’s closely parallel to the iPhone itself in this respect - is the culmination of a certain behaviorist, materialist strain of philosophy. We’ve flipped to the back of the book and we’ve seen who we are - limitlessly shallow, as dopamine-driven and addiction-prone as any lab rat. Next stop is to acknowledge that, know that that’s our nature and try to be something more.

THE NUCLEAR RESURGENCE

2022 has turned out to be, of all the unexpected pieces of good news, the year of nuclear energy. The U.S.’ Climate Bill includes a healthy support of the nuclear industry, and Germany - which ten years ago seemed to signal the death-knell of the nuclear industry with its Energiewende and decision to close down its existing nuclear power plants - has reversed course and in public opinion at least, according to this poll from Der Spiegel, now sees nuclear as a key part of an energy package.

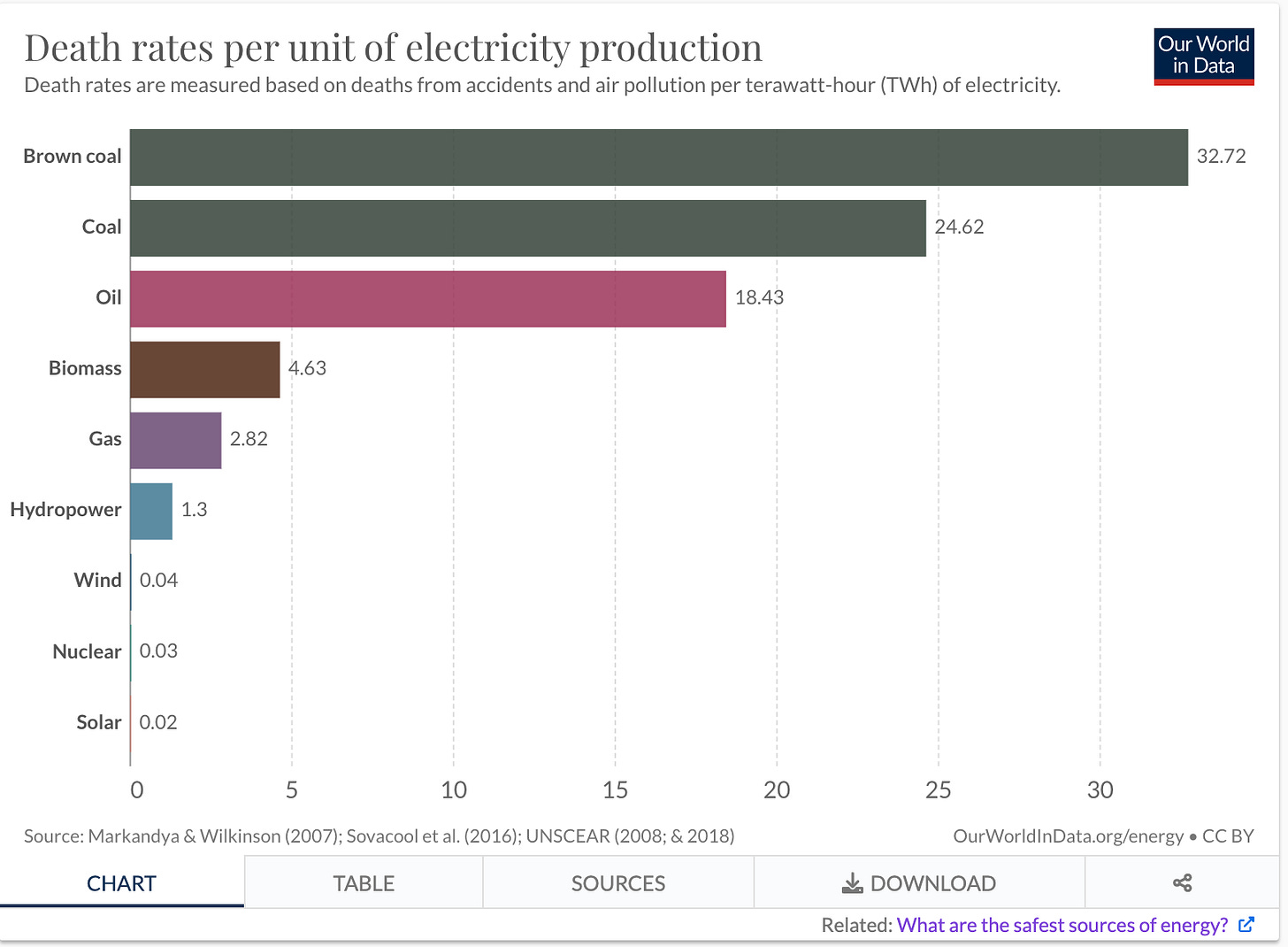

The reason I care so much about this issue is that I worked on a documentary piece about nuclear power a few years ago and it was a really stunning experience - one of these times when, by learning a lot about something, you realize how vast the gulf is between public perception of an issue and its reality. Diving into it, you understand that nuclear power plants are much safer than anybody seems to realize, that the famous industry-crippling accidents, Three Mile Island and Fukushima, actually weren’t the catastrophic events that they have become in popular imagination - the loss of life from Fukushima, for instance, was from the earthquake and tsunami, not, as everybody seems to remember it, from the meltdowns in the Fukushima Daiichi plant. (In this conversation, Chernobyl is the more difficult discussion topic, but, actually, a deep dive into Chernobyl turns out to be very surprising - suffice it to say that some of the more alarmist projections of cancer clusters came through a sort of mark-to-marketing accounting to be codified as actual results and that Chernobyl is, fundamentally, a moot point, nuclear power plants simply aren’t built like that anymore, with no containment structure whatsoever around the reactor.) And, meanwhile, the other argument against nuclear power plants - their high cost - is a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy, the nuclear industry subject to extraordinarily tight regulation and high standards that aren’t dreamt of for any other energy source.

The bottom-line with nuclear is that, in the 70 years of the nuclear power industry, less than 500 people have lost their lives from it (yes, that includes Chernobyl, as per UNSCEAR’s assessment, but if one accepts instead the measurements of a different U.N. agency then that number jumps to the low thousands). That’s very different from the 8 million every year that have their lives significantly shortened from fossil fuel air pollution as per a recent watershed study - a number that doesn’t even take into account the impacts from fossil fuels’ contribution to global warming.

For me, what the nuclear issue really represents is a kind of litmus test of how serious we are about addressing global warming. It’s very difficult to fight on all fronts at the same time. The environmental movement had its galvanizing moments in the anti-nuclear crusade in the ‘70s and ‘80s - this was a pivotal organizing successes, building grassroots support, convincing governments to shut down expensive power plants. In the midst of that enthusiasm almost nobody stopped to think that nuclear power plants really were very different from nuclear bombs and that the shortfall of nuclear energy would be made up for by burning more coal.

Now, with global warming understood to be the existential threat, the environmental community has had a very difficult time letting go of its energy purity and of its kind of founding successes in the shut-down-the-nuclear-plants-movement.

All of which is to say that I’m really heartened by this poll out of Germany. It indicates a new realism about energy consumption, an understanding that if we really want to address global warming we can’t, for reasons of a once-in-generation-accident, ignore an energy source that has zero carbon emissions and is industrially scalable. And there’s an understanding at the same time that dependence on foreign energy results in a reality like what we are dealing with at present, Germany essentially held captive by its need for Russian gas.

The ready-at-hand solutions have been to burn more coal and to try to wish away the Ukraine invasion. The press has proposed ideas like ‘embracing the darkness,’ which is kind of nice in spirit but isn’t going to happen, while The New Yorker seems ready to dismiss nuclear power plants altogether because they’re too complicated. And, meanwhile, the German public, like American lawmakers, do actually seem to get it, that energy policy going forward has to be pragmatic, that prioritization has to be given to global warming and to energy security and that a slightly-unpalatable option like nuclear is, in point of fact, a necessary component of an energy repertoire.

And in terms of the war in Ukraine, this is the important question of the moment - how does the West live, long-term, without Russia. It seems very clear that Putin, attuned to the West’s news cycles, is banking on the West gradually losing interest in holding Ukraine. The slowness of certain weapons shipments, the alarming development, as reported by The Wall Street Journal, that Ukraine is running out of cash to pay its troops and is waiting on promised aid from the U.S. to do so, all point towards the shrewdness of Putin’s bet. To combat that - if the West is serious about long-term support for Ukraine’s sovereignty - it is necessary to think in this way, to look for homegrown energy options, to weather a degree of economic hardship, to try to be a bit creative in being self-sufficient.

ATHLETES ON TRIPS

Maybe not incredibly significant but I was thrilled to scroll through the news - kind of giving myself a rest by reading sports pages and to bump into articles here and here matter-of-factly discussing pro athletes’ use of ayahuasca. Widespread societal acceptance of psychedelics and plant medicines has happened so quickly and, in a way, quietly, as to be really staggering - and the kinds of people who are vocal in embracing these medicines (pro athletes, Navy SEALs, etc) are sort of the last people you would expect anywhere near indigenous shamanic medicines.

Aaron Rodgers and Kerry Rhodes aren’t the first marquee athletes to openly discuss plant medicines. Lamar Odom credits ibogaine for renewing his lease on life in the aftermath of a suicide attempt. Mike Tyson has a very moving interview discussing how an experience with 5-MeO-DMT was the first moment of genuine happiness he had ever had - vastly more so than any boxing accomplishment.

I guess there are two reflections on this. One is that it’s genuinely exciting that we’re in an era where athletes increasingly view themselves as public figures with a stake in social issues. Everybody knows the absurdity of the outsize attention we give to athletes but nobody seems capable of doing anything about it - we just love sports too much. But, in an era in which it seems to be difficult for a variety of reasons for publicly-appointed leaders, politicians, public intellectuals, etc, to boldly take controversial, idiosyncratic positions, a cadre of opinionated pro athletes have felt secure enough in their careers to express themselves courageously. I’m thinking of Kaepernick taking a knee, of Naomi Osaka and Simone Biles skipping major events for mental health reasons, of Megan Rapinoe’s openness on LGBT issues, of Novak Djokovic and Aaron Rodgers’ insistence on their right to decline vaccination, and, now, the advocacy of athletes like Rodgers, Tyson, Rhodes for hippie-sounding endeavors like ayahuasca ceremonies. My point here has nothing to do with the validity of any one of those positions, which range all the way across the political spectrum. The point is that athletes, in a way that’s really struck me, seem somehow to have rediscovered their capacity to speak for themselves and, in so doing, to connect with a mass audience. This was the same impulse of a generation of athletes in the late ’60s, Jim Bouton, Curt Flood, Tommie Smith, John Carlos, Muhammad Ali, etc. Much of the idea of free agency was to secure this sort of independence for pro athletes - to be their own actors as opposed to working at the whims of their club - but this impulse towards independent expression seemed to fall into abeyance in the ensuing decades of tight corporate control, and now, unexpectedly, it’s back, and it’s very heartening to come across a type of courageous individualistic speech, public figures putting their careers on the line for something that they believe in.

The other reflection, though, is that as plant medicines enter further into the mainstream they are treated more and more as commodities or as elements of a certain kind of lifestyle. Apparently, Americans just can’t help themselves - everything becomes a commodity. And no matter that people like Rodgers and the documentary featuring Rhodes are actually very respectful of the traditions underlying plant medicines, seeing them as a different way of perceiving the world as opposed to just another raw material ready for export. The documentary on Rhodes follows the instructions from a shaman and cuts away before the vomiting portion of an ayahuasca ceremony - which sits poorly with the media reporting on it. “Disappointingly the documentary doesn’t show Rhodes purging into a bucket” moans The Guardian of that decision. And same goes for the reporting on what Rodgers, etc, are up to. The feeling is that here’s another cool thing that top athletes do that you yourself might want to try if you’re a little kooky and really interested in optimal sports performance. Rodgers, who seems to be a really thoughtful guy, is actually saying something quite different. “A lot of healing went on,” he told a very-perplexed reporter for NBC Sports. “There’s things—images from the nights, the journeys—that will come up in dreams. Or during the day I’ll think about something that happened or something that I thought about. It’s constantly trying to integrate those lessons into everyday life.” I can’t tell if Rodgers concerned about the depletion of ayahuasca from the Amazon or the expropriation of an indigenous tradition - both of which are major issues - but he clearly does get that using ayahuasca isn’t like taking HGH or wearing titanium necklaces, that it’s about fulfilling the part of himself that isn’t just a quarterback, and that he is advocating for plant medicines as a spiritual endeavor as opposed to some sort of athletic performance enhancer.

I was never an Aaron Rodgers fan before now.

I do find it unconscionable what Rushdie did. Interesting to know that Roald Dahl is such a scold!