Commentator

Facebook and the FBI, A.I.'s Breakthroughs, Addiction Surgeries, Post-Constitutionalism

FACEBOOK PLUS FBI TIP AN ELECTION - AGAIN

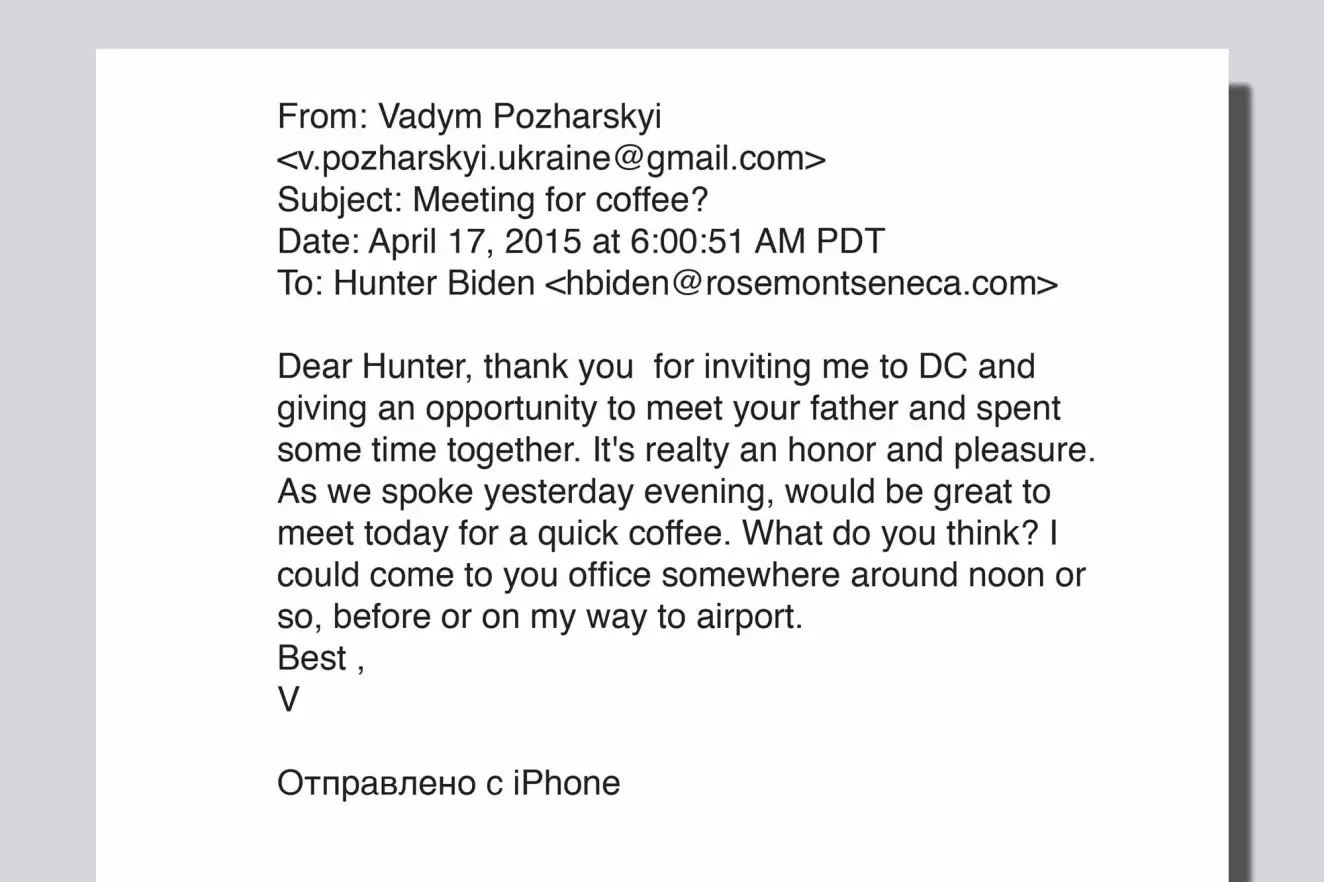

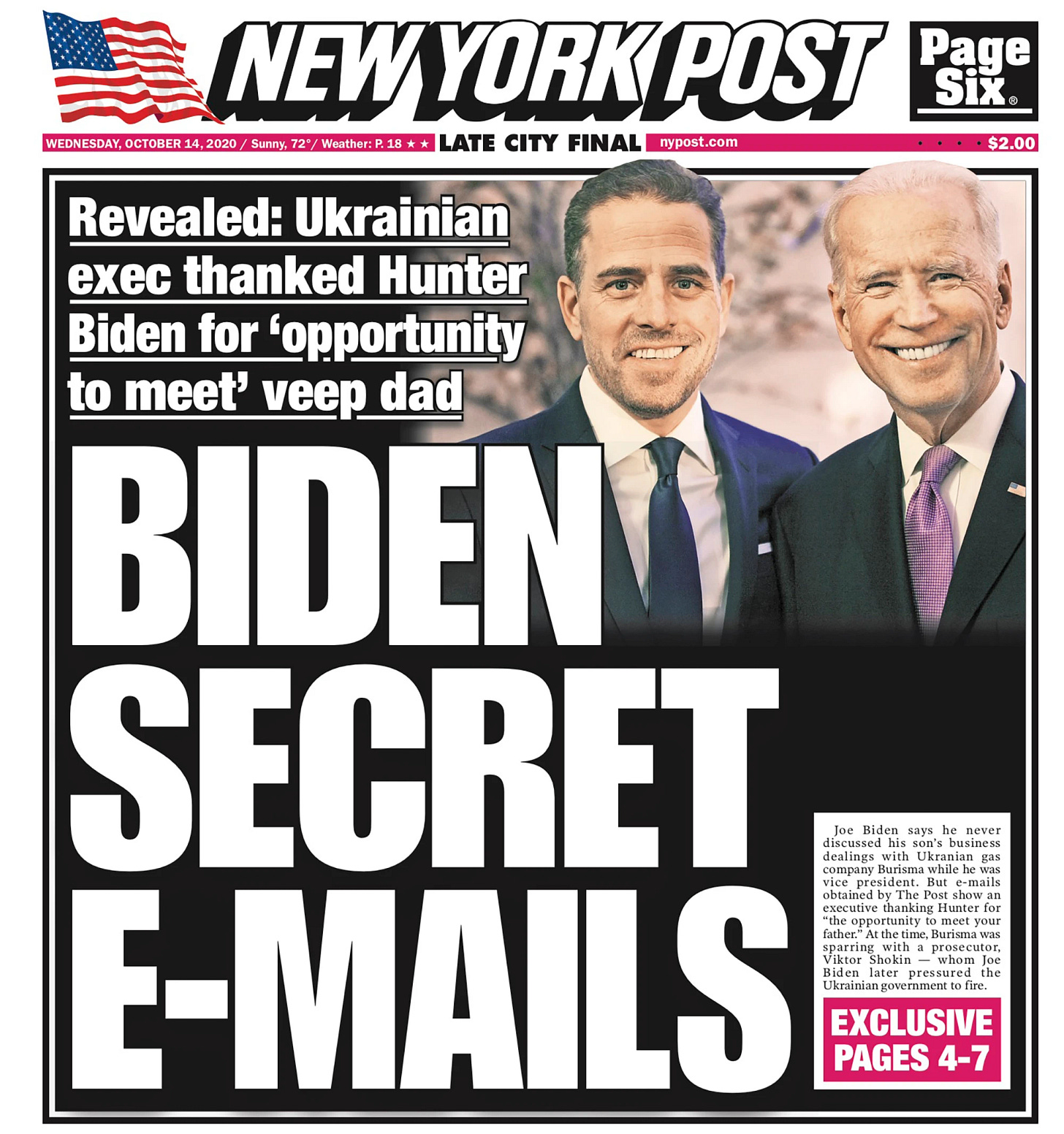

On an interview with Joe Rogan, Mark Zuckerberg admits that he essentially spiked the New York Post’s story about Hunter Biden’s laptop in the weeks before the 2020 election - and did so as a result of a request by the FBI.

There’s so much about this story that disgusts me, but here’s what really matters the most - that there hasn’t been a word about it in The New York Times, Washington Post, etc. The BBC discusses it at some length. CNN mentions the revelation but buried beneath a recap of Zuckerberg’s hobbies.

Freedom of the press is supposed to matter to the press. The New York Post came up with a real scoop from the laptop - the revelation that Joe Biden really did, at Hunter’s behest and in spite of his denials, meet with an executive of the Ukrainian company hiring Hunter Biden. I have to admit that I didn’t pay any attention to the story when it came out, I don’t think because of Facebook’s “distribution decrease” but because of the old-fashioned partisan reason that nobody ‘mainstream’ picked up on the Post’s story. And the story by itself isn’t really so appalling - it’s just a dirty mix of business and politics, a bit of nepotism, nothing to compare to the Trump outrages.

But the notion of a free press is that a story, if it’s not libelous, gets to run along its normal distribution channels, and that’s what Facebook, in collaboration apparently with the FBI, managed to suppress. The legal void here is, of course, that Facebook has no particular responsibility to the New York Post or to any principle of freedom of the press, that it can do whatever it wants with its algorithms. And, as a result, Facebook through an algorithmic manipulation (‘distribution decrease’ being Zuckerberg’s remarkable phrase) - and a pretense of concern over the facts of the Post story - buried the piece during the critical period and, as a result, may well have tipped a close election.

In theory, the Facebook moderation protocol is not supposed to have anything close to that kind of power - but the journalistic outrage about it is conspicuously missing. Basically, for two elections in a row, FBI interference at the last moment and Facebook’s arbitrary content moderation made the critical difference. When the Democrats lost that meant an outcry from the mainstream media on FBI meddling in the election and on the need for Facebook to adopt tougher moderation procedures. When the Democrats won - no concern at all about either issue.

It’s odd for me to rail against this. In some sense, I wouldn’t want it any other way - it’s completely possible that Zuckerberg, of all people, may have saved the world or at least the remnants of democracy by keeping Trump out of a second term. But if there is to be any sort of political center in this country and any kind of respect for civic institutions, it’s incumbent on responsible parties to acknowledge wrong and to attempt to be at least somewhat even-handed. It’s perfectly possible to say that the world was better off with JFK’s election, that Mayor Daley in his corrupt way may literally have saved the planet by getting Kennedy in the position to make decisions when the Cuban Missile Crisis hit, but that, at the same time, dead people voted in Chicago and that may well have tipped the balance in a close election. And same goes for an offense like this. The Post’s story was politically incendiary as well as true. It easily could have cost Biden the election - Hillary had lost for less. The FBI had no business trying to quash the story and Facebook had no business taking the FBI’s hint.

There are real lessons to be learned here. The main one, I suppose, is that Facebook (Meta), as a private entity, is really just a cancer on our political life. Facebook’s core purpose is to be a community bulletin board. That’s what it was founded as - as a digital extension of a college’s student directory. Zuckerberg managed to get ahold of that community function and we’ve been paying the price ever since. The argument of Chris Hughes, the Facebook co-founder, that Facebook is essentially a utility and should be subject to antitrust is basically right - and a case like this demonstrates that perfectly: Facebook has authority over an issue that’s clearly in the public interest (the dissemination of a newsworthy story during an election cycle) and subjects that issue to algorithmic distortion that’s driven by profit maximization even more than it is by partisan preference. We are overdue for a progressive era in so many respects and maybe in this as well - some sort of public control over our community bulletin boards. But whatever. There was no interest in following through on Hughes’ suggestion when he made it - and, in any case, there’s no more of a public appetite for antitrust than there is for a living wage.

The more immediate concern is with the press - and the apparent self-appointed task of the mainstream media to suppress stories that contradict their particular slant. The FBI/Facebook story is a perfect illustration of the new mechanism of censorship through ‘fact-checking.’ In this case, the New York Post had actually done the work, had a non-libelous story that they were willing to bring to the public that they felt could hold up in court. That story runs against the political desires of the FBI, and, as Zuckerberg put it in his hapless way, “We just kind of thought, hey look, if the FBI - which I still view as a legitimate institution in this country, it’s very professional law enforcement - comes to us and tells us that we need to be on guard about something, then I want to take that seriously.” So enter the process of ‘fact-checking,’ which means, very overtly in this case, suppressing a story for the period of time when it is relevant. The mainstream media was unwilling to support a colleague facing brazen censorship from Facebook. This was understandable at the time given the existential need to keep Trump from being re-elected - but less understandable now when Biden is in power and Joe Rogan seems to be the lone figure capable of asking the right questions. Zuckerberg himself admitted a certain culpability in the episode. “It sucks,” he said. “No one was able to say it was false.” So it’s worthwhile by the same token for the mainstream media to consider what it really stands for. Publications like The New York Times and Washington Post earned their credibility over a long period of time by being fairly balanced, by reporting stories that ‘held truth to power’ even if those stories happened to run against the political affinities of the editorial board. In the general loss of faith in the mainstream media - the sense that the legacy publications act more as suppressants and spin machines rather than genuine news organs - the publications have no one to blame but themselves.

MOMENT OF TRUTH ON A.I.

A valuable op-ed by Kevin Roose in The New York Times not saying anything particularly new but making a simple, important point - A.I. has reached the point where we need to figure out a viable response to it.

On the policy side it seems like there’s nothing much anyone can do short of a moratorium that nobody seems to be very interested in politically. The genie is out of the bottle and we’re going to live with the consequences for a long time. If A.I. weapons don’t sound like the scariest thing in the world to you, they probably should. Roose’s blithe prediction that A.I. will probably in the next decades “eliminate most white-collar knowledge jobs” seems pretty inevitable as well. My sense is that whole industries, translation for instance, are quietly becoming obsolete - with A.I. replicating, in a white-collar space, the swathe that machines cut through the blue-collar work force over the past century-and-a-half.

Roose’s suggestion of more of an interface between Capitol Hill and Silicon Valley (“A.I. boot camp”) is sweet but the kind of milquetoast position paper idea that op-ed writers are supposed to come up with. It seems not completely impossible to shut off the spigot on advanced technologies - as far as I can tell, that’s what happened with cloning, that it was simply sort of decided that cloning was unethical and there would be no federal research funding for continued studies - but the consensus seems to be that everybody is just too curious to see where A.I. will lead, and the competing weapons systems alone would make any government reluctant to move away from a branch of promising research and cede a tactical advantage to rivals.

So what’s left for us at the moment with A.I. is just to deal with it spiritually and existentially. For a long time a certain strain in our thinking equated being human with being intelligent. Archetypes here include Francis Bacon, Goethe’s Faust, the Ulysses of Dante and Tennyson. The vision is of human beings as supreme predators capable of dominating the world through our superior brains and sort of duty-bound, given our nature, to seek after all possible corners of knowledge. And now, whoops, we have created something that is more intelligent than we are - and, sooner rather than later, created a predator more dangerous than ourselves. The only viable response is to revise our self-conception.

Being human starts to seem less an exception from the general dispensation of things and more a matter of being just another creature hanging on desperately for survival. The ethic of conquest, dominion, mastery starts to go out of us replaced by an ethic of amateurism, mutual support, second best-ness.

Roose is wrong to say that an A.I. program beating the best humans in Go was a “fun party trick.” Mastery at Go is just about the most impressive thing that an individual human can accomplish. Go is an ancient activity - a game as complicated as any art. The people who master it are geniuses. And it was harrowing to watch - as recorded in the documentary AlphaGo as Lee Sodol, the genius of geniuses, the reigning Go champion, found himself outclassed by a superior intelligence. He took it badly, took it as a deep shame - and, I feel, he was right to. There is a sort of a ceiling to the intelligence of the species and it is an excruciating experience to realize that not only can we not go beyond that but our toys can - and, in place of the pride that has been sustaining us for a long time, comes a very deep humility.

I am closer to chess than to Go. Chess had its moment of reckoning with the machines in the late ’90s and, with the advent of A.I., it’s basically a joke. The latest-and-greatest machine played millions of games with itself in an afternoon, more than have been played in the human history of chess, and is now playing at a level that no human can touch. And in terms of the enjoyment of chess - it actually doesn’t make much of a difference. A present-day chess player has to let go of the fantasy that they themselves will be the best at the game and settle for their mistake-filled, blunderous chess against similarly error-prone human chess players - which, trust me, is much more fun than playing against a machine. And same goes for ‘art’ created by A.I. Who cares if its music or writing is ‘better’ - already, A.I. can write articles that fool just about any reader. The point of art isn’t actually about making something ‘good,’ it’s about making something true to the soul of the artist and creating a connection between that person and anyone else lucky enough to come into contact with their work.

The hope is that the economy of the future will be driven by some similar ethic of amateurism. I’m thinking of the kind of experience people have when they leave the West and suddenly find themselves facing wildly inefficient economic systems. In City of Djinns, William Dalrymple has a nice description of renting an apartment in Delhi as a recent university graduate and being greeted the next morning by six employees, a driver, gardener, cook, sweeper, bearer, and washer. These were all jobs that Dalrymple and his wife could easily have done but that wasn’t the point - the point is that ‘economy,’ as it’s understood in most of the world is about exchange and the subsistence of the community. The Western, Taylorite idolization of efficiency is the exception not the norm. Agricultural and then blue-collar livelihoods in the West were destroyed, ultimately, in subservience to that ethic of efficiency. White-collar workers, presumably, will be even more outraged as the machine comes for them - and the hope I have is that that’s the moment for shifting sensibilities. Forget about the worship of intelligence and of its corollary, efficiency. However stupid and inept humans may be, the purpose of machines is to work for them and not the other way around.

SURGERY FOR ADDICTION

Harper’s has a lovely, well-reported story on Deep Brain Stimulation surgery, a novel, radical treatment for dealing with severe addiction. The approach is so intense - implanting electrodes into the brain - that it’s unlikely to ever become widespread (the experimental surgery is, at the moment, limited to ‘end-stage’ drug addicts i.e. people who have exhausted other treatment methods and are likely to die imminently). But at the same time it is a kind of ethical watershed, a way of thinking differently about addiction and the medical lengths we are willing to go to for counteracting it.

The good news, I suppose, about this is that we’re at least framing addiction in the right way. The stigma around it - a long-standing obstacle - seems to a great extent to have evaporated and, with that, the old character-building model for how to combat addiction, to treat it as essentially a moral failing and to emphasize reformation of the character of the addict. The new model is closer to the ‘sickness’ metaphor for addiction - treat addiction as something that simply went wrong along the way in a person’s life and intervene the same way one would for any other disorder. Nora Volkow, head of the National Institute for Drug Abuse, is quoted in the article saying, “Addiction is a disease of free will,” which is a surprisingly existentialist statement for a hospital administrator and emphasizes that we sort of are on the right track in our approach to neuroscience. If philosophers are, ridiculously enough, claiming that free will is an illusion and that everything is just brain chemistry, the neuroscientists themselves seem to know better - that there are elements of the brain that are capable of making, for all intents and purposes, ‘free,’ autonomous decisions and that the abiding terror of a disease like addiction (or maybe trauma more generally) is that it interferes with the brain’s freedom.

At the same time, though, the very concept of the Deep Brain Stimulation surgeries scares the shit out of me. DBS surgeries and the Stellate Ganglion Block surgeries with which I am more familiar (the Stellate Ganglion Block surgeries are used to treat PTSD) literally are exactly the kinds of operations that Alex DeLarge is made, eyelids peeled back, to undergo in A Clockwork Orange. They represent very deep interference with the brain and with the core biological identity of human beings, and their avowed aim, just as with Alex DeLarge, is to turn anti-social elements into ‘good scouts.’ In the case of the Stellate Ganglion Block surgery, that’s by “pruning extra nerve growth and eliminating the source of often life-crippling sensory conditions,” in the evocative words of Eugene Lipov, the procedure’s Johnny Appleseed. In the case of DBS, it’s an electronic impulse generating a steady supply of dopamine while its cessation results in almost-immediate anxiety. And the results do have a wholesome PSA feel to it that I personally find a bit stomach-churning. “He now worries about his credit score and getting to work on time instead of where to find drugs or scam cash,” The Washington Post reported on Gerod Buckhalter, patient zero for the DBS procedure in the addict population.

So what to do? Or - to put it better - what’s a reasonable moral stand to take? The surgeries themselves may be somewhat moot points. It’s clear that the DBS surgery can be effective but in a tiny trial of four, two patients have already relapsed and with the surgical team going so far as to “remove the hardware” from one of the test subjects. Experts in the field claim DBS “will always be a niche.” And if that sounds like protesting-too-much there is a good reason for it. The surgeries are costly and likely always will be. “It’s certainly not going to solve West Virginia’s drug problem ‘one chip at a time,’” as Zachary Siegel, the author of the Harper’s piece, writes.

But look. These clearly aren’t the last of this type of super-intrusive, personality-altering surgery. This is going to be a part of the bioethical landscape we’re dealing with for a long time to come. I personally am much more interested in the breakthroughs coming from a very different and unlikely direction - from the sort of plant medicines and hallucinogens that have been used by healers since time immemorial. These are iboga, ayahuasca, mushrooms, etc, and lab-produced counterparts like LSD and MDMA. A just-released study shows that psilocybin - a polite name for ‘magic mushrooms’ - leads to an 83% decline in alcohol consumption among heavy drinkers. That’s on par with all sorts of benefits discovered in psychedelic research ever since the restart of government-sanctioned psychedelic testing in the 2000s - and on par with the really staggering underground-and-off-shore successes of ibogaine in treating opioid addiction. To me, magic mushrooms and African plant medicines are a much nicer, as well as statistically more effective, method for dealing with addiction than surgeons drilling holes in skulls. (Neuroscience, by the way, is catching up to what healers have known for a long time and is finding that the psychedelic treatments have a remarkable ability not just to deal with symptoms of addiction but to reset the brain in much more holistic ways, restoring the brain, as far as anybody can tell, to something like its pre-addictive state.) But the medical industry is no more likely to turn over the basics of its addiction treatment to psychedelic therapies than it is to ‘solve West Virginia’s drug problem one chip at a time’ - and, actually, the surgical method may make more sense from a health insurance reimbursement perspective.

So at the moment we have two dueling breakthrough methods in dealing with extreme addiction - hallucinogens, which work but are wending their way through a precarious legal path, and brain surgeries, which may not have the same efficacy and likely have all sorts of terrifying side-effects but really do represent a remarkable medical frontier. The recovery system we have in place at the moment just isn’t even close to working. As Siegel astutely notes, “There is no nationwide rallying cry to flatten the curve of overdose mortality, no daily public health briefings. Americans, and those born in the Eighties and Nineties in particular, are dying prematurely en masse, and this fact rarely rises to the level of the national conversation.” And the combination of talk therapy, faith-based programs, and maintenance drugs is - notwithstanding the incredible efforts and good will of people in the industry - badly overmatched by potent lab-created addictive drugs that become increasingly potent from generation to generation. To put it another way, Jesus plus methadone isn’t nearly strong enough to handle heroin let alone fentanyl.

That leaves us contending with the medical ethics of these sorts of intensive brain surgeries that have already passed the proof of concept stage and are likely to get increasingly efficacious. And I would have a very difficult time arguing, on any sort of utilitarian grounds, that they shouldn’t be available for people in psychic distress who have exhausted other options and need them. “We don’t have much to offer for end-stage illness and boy we’ll take it,” said Darin Dougherty of Massachusetts General Hospital in the Washington Post article.

So, forward with the deep brain stimulation surgeries for end-of-line addicts, forward with the even creepier Stellate Ganglion Block surgeries for “pruning away” PTSD. But at the same time we do need to understand the threshold we’re crossing - using the scalpel to dramatically alter personality, and in the case of the Stellate Ganglion Block to literally cut away a person’s hard-earned experience, and with absolutely no theoretical, ethical limit on where the line is drawn.

ENDING THE CONSTITUTION

Shame on The New York Times for a piece like this - making the claim that the Constitution is over and that liberals’ task should be to “reclaim America from constitutionalism.”

As somebody with affinity with liberal values - who is trying very hard to be liberal - I just can’t believe that liberals would go in for thinking as woozy as this.

To start with the screamingly obvious: no, it is not a good idea to repeal or to mischievously work around the Constitution. The Constitution is the rule of law for the country. Ignore it or revoke it - as the law professors Moyn and Doerfler are arguing, and you lose the rule of law, you have, sooner rather than later, violence.

To continue with the equally-obvious-but-no-less-important: the system actually is working pretty well. We are at peace domestically, the economy is functioning, and the political process, with its challenges, holds - when their term is up, everybody so far has packed up their office or made the walk to the helicopter on the South Lawn (even if they’ve tried to send a mob to the Capitol first) and that’s the most important thing, the limit on power that we have the Constitution to be grateful for. As somebody, a refugee from Russia, said to me recently with a deep sigh, “Americans just have no idea what they have.”

I don’t mean to sound so saccharine or patriotic - but it seems like somebody has to. This has been a terrible period, we all know that. The feeling is that the social fabric is fraying. But in the midst of that - and with all the famous biases of the Electoral College - we somehow have a Democratic president and Democratic congress, and this is the moment when Drs. Moyn and Doerfler blithely call for reshuffling the cards and starting from scratch? An institution like The New York Times, just like Yale and Harvard Law School, has a vested interest in protecting the civic order. It’s perfectly possible that it will pull apart in my lifetime, that we’ll see what a broken system really looks like, and if the civil war that people are almost casually talking about really does happen it would likely be the proximate fault of the extremes, the MAGA crowd and maybe their ultra-progressive counterparts, but good liberals have their role to play in the drama as well i.e. by not fanning the flames, by not toying with radical proposals like this one. And if things really do collapse, and the Constitution gets suspended along the lines of what Moyn and Doerfler are describing, one wonders what the justification for that will be, what great cause we would believe we were agitating for - that we lost faith in the civic order itself because of what? Because we didn’t like the Dobbs decision? Because we felt that there were a few too many Republican Congressmen from underpopulated states?

I have been seeing this idea floating around and have meant to engage with it before - it’s usually phrased as ‘the Constitution is showing its age,’ as printed here and here. There seem to be two strains underpinning this mode of thought. One is a classic liberal - or I should really say federalist view - holding that the Constitution from its inception was a highly imperfect document compromising away too much power to the states. The belief is that America fulfills its logical political destiny with a kind of turbo-charged federal government, as under Lincoln, FDR, and the Great Society. This is an interesting case, it’s made evocatively for instance in Master of the Senate, and the linchpin of it is a sort of close reading of Lincoln’s behavior during the Civil War. The idea there is that the republic collapsed almost from the beginning under the weight of the slavery issue and that, by the time of Lincoln’s accession, the Constitution was a dead letter. The dirty secret all this time has been Lincoln’s conscious suspension of constitutional rights - notably the writ of habeas corpus through the Civil War - and Moyn and Doerfler are proudly hoisting a new book by Noah Feldman to make the case that Lincoln acted essentially as an extra-judicial president and that his willingness to supersede the Constitution was precisely what made him great. But this, I would contend, is a creative misreading of Lincoln’s legacy - and not at all what he intended. His point was that certain constitutional liberties were suspended in an extreme emergency - a shooting civil war - and were restored as soon as the fighting ended. The critical-and-long-overdue reformation was made within the text of the document itself, through three new amendments, rather than through some abandoning of the constitution altogether.

That federalist, hyper-unionist strain has been joined recently by a progressive argument holding that, since important elements of the voting bloc, e.g. women and African Americans, were not given a political voice at the time of the Constitution’s ratification, then the constitution is an invalid document. This is the idea that Moyn and Doerfler are playing to when they write, “It’s difficult to find a constitutional basis for abortion or labor unions in a document written by largely affluent men more than two centuries ago” and “It would be far better if liberal legislators could simply make a case for abortion and labor rights on their own merits without having to bother with the Constitution.” That argument gained ferocious ammunition recently from the majority decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, which held that what mattered in interpreting the Constitution was the state of public opinion at the time of the adoption of the relevant amendment. In this case that was the 14th Amendment in 1868 and, since public opinion seems not to have been particularly favorable to abortion then, ipso facto there can be no current constitutional law protecting abortions. That extreme hypocritical originalism - a late-breaking development in constitutional law by the way - creates not so surprisingly an equal and opposite reaction, which is for the Dobbs dissenters to write in so many words that they were being held hostage on the bench and that the Supreme Court has lost its credibility and for legal scholars like Moyn and Doerfler to say the hell with it, that if people like the originalists can win then they don’t want to be part of the game.

In theory, there is something to this. The American experiment originated in a state of heightened uncertainty between ‘democracy’ and ‘republicanism’ with that fissure immortalized in the parties’ names. We don’t usually think about it this way, but America from the beginning went in a conservative British direction emphasizing representation and a baroque system of balance of powers as opposed to the soon-to-be unveiled French system of popular sovereignty. It is possible to imagine turning the clock back to more or less that moment, calling a popular referendum to supersede the Constitution and, if that passed, writing a new founding document with no Senate, no electoral college, and much closer to a direct democracy. I wouldn’t be surprised if in the next years we start seeing calls for a referendum somewhere along these lines.

But it would be a horrible idea. As is, the Constitution really is a remarkable document and we’ve been incredibly lucky to have it. Moyn and Doerfler‘s case against constitutionalism itself is a remarkably inane perspective - even some kind of fanciful referendum would likely lead to a fresh constitution and, if not, the suspension of constitutional authority altogether has a not exactly great track record in the modern world. The beauty of the Constitution is that it is evolving, is subject to amendments and to a judicial interpretation as ‘a living document.’ The issues that Moyn and Doerfler are upset about actually are addressable within the constitutional structure as it is. I’m amazed, for instance, that I haven’t seen more vocal attention anywhere for the Interstate Voting Compact, a clever bipartisan idea that replaces the electoral college with the popular vote and without running through a constitutional amendment. The overriding issue Moyn and Doerfler have - their anger at the Dobbs decision - reflects of course an unfortunate reality but what exactly are we supposed to do? Even superseding the Constitution doesn’t mean that you don’t deal with the same people. A lot of Americans are pro-life. Those beliefs and the laws accompanying them are about to be put to the test in a democratic election.

The Moyn and Doerfler piece sets like a world record for sour grapes. It’s also as out-of-touch and ivory towerish piece as I’ve ever seen. The feeling is of a law school colloquium in which politics do not exist and ideas are evaluated by how daring they are. The ‘mild’ idea of packing the Supreme Court is old hat. Moyn and Doerfler are excited by ‘the breath of fresh air’ of ideas like state-packing - the completely non-controversial non-partisan issue of adding more states (i.e. breaking left-leaning metropolitan areas into new states) so as to counteract the electoral college - or, if that is still too mild, the ‘simple’ matter of a Congress Act by which Congress would pass legislation overriding the Constitution and, among other things, effectively abolishing the Senate.

A quick scan of Twitter shows that the responses from the right are what you might expect. “Holy fuck. This is what we are up against,” writes one. “These are your domestic terrorists and radical extremists,” writes another. And they’re not wrong. If the MAGA crowd were calling for a suspension of the Constitution, The New York Times would likely denounce them as treasonous - but somehow it’s ok coming from accredited liberals. This is a really tricky moment. The feeling is that the republic - I use that word advisedly - is fighting for survival. The Constitution seems to be the one thing we can agree on - and it’s gotten us this far. For liberal professors and liberal institutions to be toying with it in this way means that they don’t understand how fragile the social fabric really is.

Great post! As we've come to expect.

I like how you put the Hunter Biden story. Not really a big deal - just some dirty politics. But why in the world is The New York Times or any other media outlet trying to bury a story like that?!