Research Scandals in Alzheimer’s and Depression

I don’t really know how to deal with this story, the dual revelation in one week that a) a whole series of Alzheimer’s studies were, per a Science magazine investigation, based on flagrantly falsified data; and b) a credible study has declared that there is “no support for the hypothesis that depression is caused by lowered serotonin activity or concentrations,” which at a stroke undoes several decades worth of sanctified medical wisdom.

The revelation about Alzheimer’s is a case of “shockingly blatant” image-tampering, in the words of one Alzheimer’s expert. The image-tampering came out of a well-respected University of Minnesota lab, which had become a stronghold for the thesis that amyloid deposits are the prime contributor to Alzheimer’s. In the mid-2000s, as that hypothesis came under critique, the UNM lab released a stunning Nature paper revealing the discovery of ‘amyloid beta star 56,’ a substance that allegedly caused dramatic memory impairment in rats. That study appeared to cinch the case of the ‘amyloid mafia’ - the Nature paper would go on to be cited in 2,300 other publications; and NIH would spend roughly a billion a year on amyloid-related research, with many millions of those directly traceable back to the Nature paper. That paper - along with seventy others prepared by the same UNM neuroscientist - turns out to be completely dismissible with the the key images in it flagrantly doctored. In terms of impact, the revelation may be relatively mild. It doesn’t discredit the amyloid hypothesis, but it indicates that millions if not billions of research money was wasted over the last decade and a half pursuing the false lead of ‘amyloid beta star 56’ - and that that manufactured consensus over amyloid helped to pave the way for the wild goose chase of Aduhelm.

.The revelation of the non-connection of serotonin levels and depression - as presented in Molecular Psychiatry - cuts somewhat deeper, at least for me. The era I grew up in - the ’90s and ’00s - was really the pharmaceutical heyday and the clinching argument for the essential benevolence of the pharmaceutical industry was its success in treating depression. I remember campus free thinkers trying to make the case that there was something wrong with over-medication and with turning one’s mental space over to drug companies - and being cut down with the counter-argument of people who had depression that their base well-being was attributable to their antidepressants. In the context of the time that argument was unassailable - and the beneficence of the drug companies seemed like one of these pieces of higher adult wisdom that I was too young to understand.

The revelation about serotonin and depression doesn’t necessarily invalidate the SSRI antidepressants - if they work they work even if their underlying mechanism is something different than what has been studied. But it DOES undercut the authority of the pharmaceutical industry which has, essentially, been altering the mental states of millions of people under false premises, without understanding what they were actually doing.

Damage is done too to the reputation of the press in covering science. The tendency has been to treat science as a separate domain from the rest of society - and to hold to a belief that science exists in a very pure and uncorrupted state in which appropriate checks and balances prevail, above all in the bringing of drugs to market. It doesn’t matter that this belief has been abundantly disproven - the opioid crisis comes to mind. And it isn’t really surprising that a pair of bombshell revelations - the falsification of Alzheimer’s data and the the lack-of-connection between serotonin and depression - aren’t widely reported on and seem not to shake some underlying trust in the ‘scientific process’ wherever it may lead.

Where the Molecular Psychiatry serotonin paper is reported on at all, it’s treated shruggingly. Vice writes, for instance, that the non-connection of serotonin levels and depression had long been known in the mental health industry - the hypothesis had been discreetly dropped some time ago - and that the Molecular Psychiatry paper is itself concerning as it is “being used to make misleading claims about antidepressants….and that clinicians and psychiatrists are worried about the framing of the findings, which are being used to question and utility and efficacy of antidepressants.”

But this is really irresponsible. I remember being impressed, in my early 20s, by somebody I knew who had tattooed the word ‘serotonin’ on his forearm - the idea was to be reminded of ‘chemical imbalances’ every time he was feeling low, for his tattoo to be a supplement to his antidepressants. The theory of chemical imbalances cut very deeply across the society - it created a sort of ethical imperative for anybody feeling the symptoms of depression to seek out medication; and it generated a stark divide between those who weren’t ‘clinically depressed’ and those who were and could be understood, really, only by their psychiatrist. Evidently, the response of the medical industry to the Molecular Psychiatry paper and to the quiet jettisoning of the serotonin hypothesis is to shrug and spin - to be concerned only for the impact on ongoing treatments. The right scientific response, of course, would be to reexamine. If the serotonin hypothesis was always unfounded, then widespread questions are raised in how we think about depression altogether - and whether it’s as narrowly compartmentalized to underlying brain chemistry as the pharmaceutical industry tends to assume. As Joanna Moncrieff, the lead author of the Molecular Psychiatry paper, writes, with dignity, “People need this information [from the study] in order to make properly informed decisions about whether to take antidepressants. Even if leading psychiatrists were [by c.2005] beginning to doubt the evidence for depression being related to low serotonin, no one told the public. To this day people continue to be told by the media and some in the medical profession that depression is due to a chemical imbalance.”

This has, I suppose, turned out to be the reality critical question of our era - the question of whether the non-professional public has the right to question the dictates of the scientific community. It’s a touchy subject because science has, to a remarkable extent, become our underlying faith. Science, as we conceive of it, has two primary arms. One is Baconianism - which usually passes under the name of ‘progress’ and represents a very cozy societal vision by which we are constantly ameliorating our material surroundings through a continual process of trial-and-error. And the other is ‘consensus,’ the belief that at a certain point in time scientific questions become settled and from that moment forward no longer permit of debate. The journalistic shorthand here is to discuss the ‘war on science’ - which pits the scientific community as the custodians of truth and progress against an army of MAGA-hat wearing paleoliths.

Actually, there are real problems with both planks. Baconianism is, essentially, just a philosophy but tends to be treated as some sort of ineluctable force - it yields ever-unfolding technological gains that often have nothing to do with human thriving (c.f. ‘autonomous weapons systems’ below). And the process of ‘consensus’ is as prone to corruption as any other human endeavor and tends to default to whatever is most profitable or suits the powers-that-be. The twin scandals double as a neat summary for the problems with both approaches - Alzheimer’s treatments garnering vast amounts of money under the premise that the wheels of science must keep moving forward even if the research is shakier-than-presented; and a dubious proposition about the neuroscience of depression passing unchecked through the society as ‘settled’ science. The way out of Baconianism is in the domain of politics and of philosophical debate - taking public ownership of questions that have been cordoned off into science. The way out of the ‘consensus loop’ is just better science - an understanding that science is never actually settled and that science demands that its conclusions be constantly questioned.

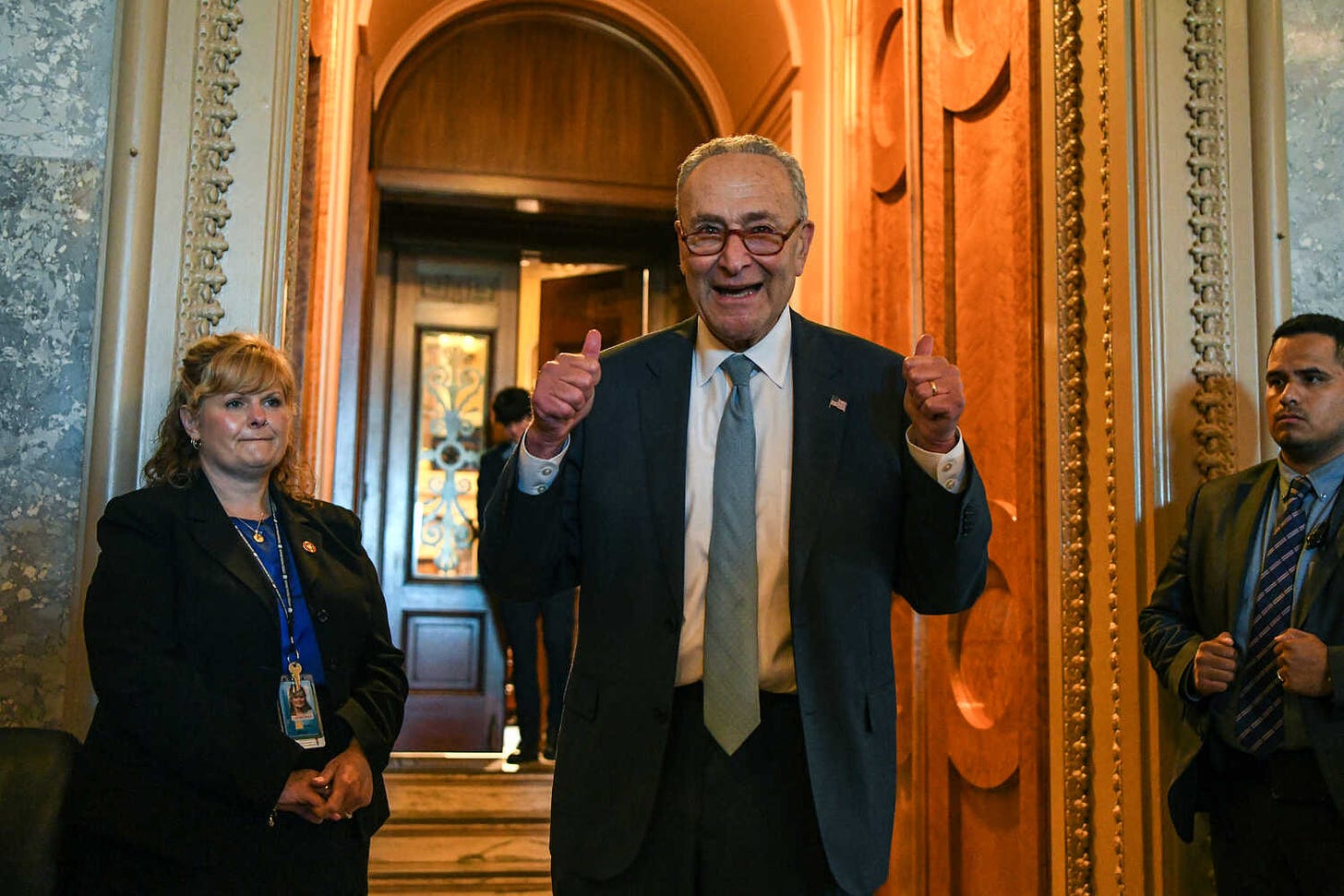

The Climate Bill

What to say about the climate bill? Biden probably is right to claim that this is the bill we have all been waiting for - after years of nothing at all, finally some sort of climate action from Washington. And the bill gives the sense of being just the sort of compromise where everybody’s a bit unhappy - except for Joe Manchin, who gets all kinds of pork to bring back to West Virginia.

Will it actually benefit anybody? Don’t know. In any case, I’m struck by how much more detail is devoted to the bill in Substack type publications than by the mainstream press. The mainstream analysis is all connected to Biden’s popularity - the question of whether Biden will have salvaged his presidency just enough to help carry the Democrats through the midterms and to maybe even run again in 2024. As for the impact of the bill itself, Michael Shellenberger is astute among a few serious analysts in noticing that much of it doesn’t really make sense.

Manchin’s provisions about carbon capture for coal plants and medical aid for coal miners with black lung disease are actually kind of a nice contribution from his role in this saga. The protection of nuclear plants is a pleasant surprise - the Democratic center (and, I suppose, the nuclear industry) showing surprising fortitude in sticking up to the left on the nuclear issue and recognizing that any real effort to address global warming requires nuclear as a key component of clean energy. And the vast subsidization of the renewable sector likely means what it did during the Obama administration - investment in a young sector of the economy without necessarily significantly reducing our collective carbon footprint in the short term but with hope for a genuinely greener future.

So, I guess, a great bill. The grousing on the right is that it might as well be called the expand the IRS and raise the corporate tax bill or just the Tesla enrichment bill - and its positive aspects amount to a handout for, essentially, R&D for the clean energy sector. And the potential for vast waste without leading to significantly reduced emissions is very real. On the other hand, as the high water mark of the Biden presidency, it seems sort of fitting - a reasonable statement of where the Democratic Party’s heart is and what it’s capable of achieving: a moderate contribution to the reduction of carbon emissions, a moderate amount of spending, and outsize support to a certain type of West Coast entrepreneurial class, with cutting-edge, greenish technology that may or may not ultimately contribute to helping the environment.

The Missing Middle Ground on Global Warming

Why is there no middle position on global warming? The debate is between either denialism or a radical revamping of the economy. And the voices speaking for some sort of moderation - an acceptance that, yes, there is an issue but that it’s not necessarily apocalyptic - are almost completely absent. The New Atlantis and a handful of thinkers, Steven Koonin, Vaclav Smil, Roger Pielke, Michael Shellenberger have been working on staking out that ground. Oddly enough, Joe Manchin - everybody’s new favorite Senator - hit it with surprising exactitude, working to phase out fossil fuels in ways that don’t entirely devastate local economies while investing heavily in a fresh wave of energy.

It’s possible that there isn’t too much need to fret about the absence of climate change moderation - that the democratic process takes care of that itself - and that the final form of any sort of climate bill ends up looking a lot like the one that just passed the Senate, an endorsement of renewables but with an understanding that they are not ready yet and that the complete abandoning of fossil fuels torpedoes whole swathes of the economy, a recognition that nuclear, however unpalatable to hard-line environmentalists, is a crucial piece of the puzzle. Democratic leadership seems to result ultimately in this perspective - a very similar approach to energy under Biden as under Obama.

Still, in the domain of ideas, it’s problematic that moderation itself is seen as a dirty word. The obvious-enough explanation is that, in dealing with what’s still a mostly abstract concept, everybody retreats to their respective corners. The right becomes completely denialist and just sees Communist conspiracy. The left returns to a long-held suspicion that industrialization itself was an enormous mistake and that we should power down the entire society - which just isn’t going to happen and is basically an inhuman perspective to take.

The way out is to forcibly insist on a middle ground. I’m really enchanted by Smil’s angry statement in his recent New York Times interview, as quoted by The New Atlantis: “I cannot tell you that we don’t have a problem because we do have a problem. But I cannot tell you it’s the end of the world by next Monday because it is not the end of the world by next Monday. What’s the point of you pressing me to belong to one of these groups?”

Have the capacity to see things in these terms and suddenly a whole array of options becomes possible: various types of clean energy as well as a revisiting of nuclear as well as - if push came to shove - some type of geoengineering. I am a bit startled, as each of the climate skeptics have been, to realize just how shaky aspects of the ‘climate consensus’ are. According to the global warming playbook, hurricanes shouldn’t actually be decreasing in frequency and outmoded extreme heat forecasts shouldn’t have just been left in the IPCC’s report so as not to buoy denialists. It also should be possible to say these things publicly without diminishing the case for the importance of fixing our relationship to the environment. Global warming is obviously an issue. Humanity’s relationship to the environment is clearly out of whack. But that does not mean that the environmental community gets a pass from critical thinking or from dodging facts that are inconvenient to the narrative. As The New Atlantis nicely puts it, global warming - if there is a solution - will be dealt with in the domain of politics, not strictly in science; and, in politics, it is important, to some degree, to be an honest broker, to deal with actual as opposed to projected reality, and to look for places of understanding and compromise.

AI Weapons Systems - Ho Hum

I’ve gotten to a state of being somewhat blasé about the ever-worsening world, but this interview in Der Spiegel on AI weapons systems got to me. The logic of war leads, of course, to ‘killer robots’ and to machines with the capacity to make executive life-and-death decisions. They follow, smoothly enough, from the United States’ drone warfare program and, more distantly, from second-strike capability. Their tactical merits are obvious enough - bringing cheap, lethal force to the battlefield while reducing one’s own casualties. One asks oneself what could possibly go wrong from killer robots and machine decision over life-and-death, but those concerns do not seem particularly to faze the world’s major militaries, which are blithely moving forward with AI weapons technologies. The United States has pioneered ‘autonomous’ warships, which are rapidly being cloned by the Chinese; and Russia, not to be outdone, has been moving forward with autonomous nuclear submarines. “Can you think of anything more terrifying than a submarine in which, instead of a captain, a computer program decides whether to start a nuclear war?” asks Toby Walsh in the Spiegel interview.

Good question.

Walsh, who is a very serious AI researcher, focuses on the disruptive potential of AI weapons - their relative ease to produce compared to heavy conventional weaponry and their tendency to generate asymmetric warfare. By analogy to nuclear weapons, claims Walsh, “Autonomous weapons are perhaps even more dangerous. That’s because building a nuclear bomb requires an incredible amount of know-how, you need outstanding physicists and engineers, you need fissile material, you need a lot of money." It’s the high threshold of production that, probably, has been the world’s saving grace for the last 75 years - the nuclear powers have succeeded for the most part in keeping tight control over nuclear weaponry and in avoiding a nuclear exchange - and that sort of state control over advanced weaponry tends to disappear with a new wave of lighter, more cybernetic warfare in which software engineers become the weapons techs.

But that shift in the balance of power does not, of course, come without strenuous opposition from the larger nation states. The logic of national security decrees centralization, stockpiling, a need-to-always-be-on-the-cutting-edge. And what that’s resulted in, already, is an arms race - with a few concerned citizens, Walsh, Kai-Fu Lee, above all The Future of Life Institute calling for some sort of disarmament, some regulatory protocol before this gets completely out of hand, but even the advocates seem to have little hope of prevailing over the inexorable logic of national security and weapons development.

All that I can really express, besides the obvious alarm, is a kind of residual shock that AI weapons development has not been a bigger story or prompted a wider public debate. “A global AI arms race has long been underway, of which the public has so far been largely unaware,” says Walsh - and that mirrors the widespread inability to address AI in any kind of public forum. The sense always with AI is of being presented with a fait accompli - software engineers, not to mention weapons scientists, cranking out a world-altering technology that seems, on all fronts I can think of, to be obviously a bad idea and doing so with absolutely no moral compunctions and no input from any kind of public democratic debate.

So much of what I read is so narrowly partisan. Very cool to get SOME range of perspectives.

Oh man. And my Zoloft and I had such a good long run together. (Sad face)