Commentator

Russian Nationalism, 'Show The Carnage,' Johnson's Exit, Reckoning With Mandates

The Nasty Russian Nationalist Streak

I’m aware that I’m falling into a slightly tedious theme in the Commentator of, every week, proposing a new frame for understanding the Ukraine War. A couple of weeks ago there was a discussion about Mearsheimer’s critique of NATO enlargement, last week it was the left-wingers focusing on the militarist mindset of the security state. My own inclinations point in a different direction – towards a kind of mysticism of Russian revanchism – and which I’ll write about at more length. The truth is that the origins of the war are entirely in the mind of Vladimir Putin and maybe a handful of people in his inner circle – Yuri Kovalchuk, Nikolai Patrushev, etc – and everybody else is just guessing. I feel as if I’ve gotten a semi-decent handle on that worldview through a strain of Russian thought that runs from Ivan Ilyin through Lev Gumilev and Mikhail Gefter to Alexander Dugin, Gleb Pavlovsky, etc, and is interpreted for English speakers largely by Timothy Snyder. I’m grateful to Joy Neuemeyer for identifying another lineage, which is more or less the same thing but runs through figures I’ve never heard of – Vadim Khozinov, Vassily Shukshiv, Valentin Rasputin, in a word the ‘Village Prose’ movement within Soviet literature which led to an outpouring of a Russian nationalism in the 1980s.

The critical point here – and which I think has been totally glazed over in Western accounts of the period – is that the Soviet Union did not topple over from some historical necessity (in a sense, Western interpreters could not resist mimicking the language and logic of the Marxist-Leninists) but from political rifts that occurred along national lines. And the really key event is Russia’s separatism from the Soviet Union – Yeltsin, as the chairman of the Russian Republic, riding a wave of Russian nationalism to orchestrate a kind of Brexitian coup against Gorbachev and the USSR.

I’m not sure how much anybody in the West remembers the details of intra-Party politics in 1990, but what’s clear is that that’s the narrative that stayed with Russia’s elite, that the fall of the Soviet Union was more about realignment than existential collapse. In Neuemeyer’s version, there’s a clear line that runs from Yeltin’s anti-Soviet rhetoric in 1990 – “Enough feeding the other republics!” to Dugin’s claim that the Cold War ended from Russia’s “unilateral” and rather selfless withdrawal to Putin’s depiction of the end of the Soviet Union as a remarkable achievement by the Russian people, “a peaceful transformation of the Soviet Union and peaceful transition to democracy.”

The slightly nastier formulation of the same idea is the view of Bolshevism as a Western phenomenon, a risky, experimental attempt at globalization, of which the Russian people were naïve and/or courageous enough to make themselves the initial guinea pig. (And, somewhere in unfolding this line of thoughts, its advocates tend to note that so many of the Bolshevik leaders were not only Western-inflected, but, as it so happened, Jews.) In his necessary-to-read essay ‘On the Historical Unity of Russia and Ukraine,’ Putin summarizes the history of the revolution as follows: “The Bolsheviks treated the Russian people as inexhaustible material for their social experiments. They dreamt of a world revolution that would wipe out national states. That is why they were so generous in drawing borders and bestowing territorial gifts. It is no longer so important what exactly the idea of the Bolshevik leaders who were chopping the country into pieces was….One fact is crystal clear: Russia was robbed, indeed.”

In this view – and the inner logic of it is comprehensible – the Soviet period becomes a brief interregnum, an unfortunate experiment in internationalism, during which Russia sacrificed itself for the benefit of its ‘little brothers,’ the various smaller Soviet republics. With the fall of the Soviet Union – aka Russia’s unilateral withdrawal – it’s no more nice guy and back to the original state of affairs, a Russia constituted along more or less racial and linguistic lines with some degree of hegemony (and this is of course the point in dispute) over various states within its sphere of influence.

Western critics have a startling capacity to misread Russia’s reigning ideologies in virtually ever conceivable way. Sometimes Putin is seen as a rational, reactive ‘technocrat’ (c.f. Mearsheimer or Oliver Stone’s Putin Interviews), sometimes he is bent on restoring the Soviet Union, sometimes he is simply cuckoo. As far as I can tell, though, there really is a very consistent ideology – which is close to a state religion, has appeal, an inner logic, a mystical streak, and is very dangerous for everybody else, particularly an independent-minded neighbor – and Neuemeyer is right to find a key to understanding it in the nationalities question that so bedeviled the Soviet Union.

In this steep revisionism, Russia becomes the eternal innocent, robbed both by the West and by an excess of generosity towards the republics – and Neuemeyer is right as well to find the imaginative expression of this idea in the figure of the muzhik, the Russian man who is both high and low, who is somehow gentle even in the midst of his brutality. Neuemeyer seems to blame the Brat movies for the turn of the somewhat lazy Russian muzhik of the late Soviet period into the committed Fascists attacking Ukraine. I have difficulty with that – I love the Brat movies, which are incidentally the only action movies I’ve ever seen that actually make sense – and Neuemeyer is eliding over a key component of them, Danila’s concerted search for a form of being other than gangsterism, the ways in which he would vastly prefer to hang out with the arts crowd and to chat philosophy with rival gang leaders but is compelled, by the circumstances he finds himself in, to shoot up virtually everybody he comes into contact with. But I do think Neuemeyer is on the right track. To a certain extent, it’s like we’re all living in the somewhat tiresome 19th century sorts of novels in which Russians sit around asking each other ‘whither Russia’ and ‘what this is cursed Russian soul.’ And those questions tend to be answered with the larger-than-life muzhik and his simultaneous gift for elevation and for cruelty – as seen in Babel’s Afonka, who, overcome with grief for the loss of his beloved horse, disappears from his unit for some time in search of a suitable replacement and is traceable only via rumor, “the terrible rumbling from the villages, the rapacious trail of Afonka’s marauding showing us his difficult path”; in Spirka Rastorguev, the handsome, footloose hero of Shukshiv’s ‘The Bastard’ who can’t quite figure out if he should kill the husband of a woman he likes or should kill himself but knows he has to kill someone or other; in Brat where, it’s true, Danila’s taste for soft rock doesn’t stop him from transforming into first-person-shooter mode; in Compartment Number 6, one of the few foreign entries to this genre, in which a muzhik, tender and brutal, consoles a woman by telling her “all humans should be killed” – and, actually, at that moment, his very sincere thought is the exact right thing to say to her. In the Twitter videos I’ve seen of Russian soldiers in Ukraine, they all come across like a knock-off of Spirka or Danila, the very resigned, this-is-for-your-own-good way they have of saying that they’ll unleash hell on Ukraine.

The point is to beware of myths – the myth of the eternally innocent Russian muzhik, the myth of Russia the overly generous benefactor of the republics – and to recognize that myths are never so dangerous as when they are sincerely believed.

The Nasty ‘Show The Carnage’ Argument

I was really surprised, in the aftermath of Uvalde, at the alacrity with which the smart voices in the media jumped to the conclusion that the slaughter had to be shown in visceral detail - the most horrific-possible photos published. Apparently, the drumbeat for this had been building in newsrooms for some time – a frustration about the genteel approach that the media was taking to mass shootings, all the photos of candle vigils and weeping parents, which, in this logic, kept the full horror of the events from the American public and from lawmakers and allowed the shootings to become virtually routine.

My first thought – which is probably my last thought – is that the media simply needed something clever-sounding to talk about in the aftermath of the shooting. Only so much could be said excoriating the police chief of the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District, and some drastic action was called for – which could well be the media taking upon itself the heavy burden of showing the most gruesome images of a massacre in a bid to somehow avert the course of the mass shooter epidemic.

The surprise is that the media seems to have come to some kind of internal consensus. “The news media have a clear course of action – which is to do their duty,” wrote Edward Wasserman, former dean of Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism, in The San Francisco Chronicle. “I’m so done with warning labels,” said Sue Morrow, editor of News Photographer magazine. “The time for restraint should end,” intoned Charles Blow. “The public’s need to know has overtaken its need to be shielded from horror.” And what that means is that the next time there is a mass shooting event – and we all know that there will be a next time – we should be prepared for a grade of graphic image that we haven’t seen before and, incidentally, should be prepared also for the media’s self-congratulation at finally ‘showing the carnage.’

This is a very complicated debate, actually, and the consequences of it may be more far-reaching than anybody realizes. But the first thing to realize here is that the media is not actually acting in good faith as some sort of custodian of public decency. Graphic can’t-look-can’t-look-away images mean awards for photographers and for news desks, and awards translate to sales, and once you start digging into the journalism roundtables about showing these images the conversation shifts quickly to concern about how the history of photography would have gone if not for lenient newsroom policies towards violent imagery – no Brady! no Capa! no napalm girl! – and think, too, of all the great photos that may never make it past an editor’s desk if the prohibition on the most graphic photos continues.

But the real issue with the argument of Blow, Wasserman, et al, is that the media is vastly overstating its own importance. There’s a kind of talismanic belief that exposure, transparency can cure any ill – sunlight is the best disinfectant, truth stands up to power. There are arguments to be made for this outlook within politics – although I’ve been having my doubts about it recently – but not in the psyche of mass shooters. “Imagine instead that the vast American public was forced to look at what actually went on in Robb Elementary,” writes Wasserman and then lays out a graphic prose description of the scene that I don’t really have the stomach to quote here. “How might those images of waste and desecration transform the way we now talk about what happened and what must be done?”

My guess is that they wouldn’t transform the way ‘we’ talk about things very much at all. Wasserman seems to be under the illusion that he is writing copy for Spotlight – that there is a vast American public that just needs to be mobilized, and ideally mobilized by a brave and forthright press, and then great change is both possible and inevitable. But incipient mass shooters, I imagine, don’t read Charles Blow’s column or look at photo spreads in The New York Times. They are not really part of a ‘vast public’ that can be dissuaded from what they’re thinking about doing through journalistic shock therapy. They would end up seeing some of these images filtered through their various channels, but the idea that the reality of violence would act as a deterrent strikes me as really far-fetched. The Atlantic has a very thoughtful piece by John Temple, who was the editor of The Rocky Mountain News at the time of Columbine, and who dealt, excruciatingly, with many of the questions that Blow, Wasserman, and the emerging media consensus are only pontificating about. “I worry that’s a decision that could backfire badly,” he writes. “I saw how Columbine seemed to break down a barrier for other similarly inclined killers. I worry that making public photos of obliterated children will motivate others to see how much damage they can cause, will normalize unthinkable violence, and will be used in a hateful way, against the families of the dead or as threats to others.”

The counter there is that the psychology of mass shooters is kind of a straw man in this debate – for one thing, that’s a constituency that we really shouldn’t take into account; and, for another, the focus really is on the legislators who are in thrall to the NRA and refuse in the face of all that is holy to ban assault weapons. But the counter to the counter is that the legislators in question are clearly locked into their beliefs and their votes – if twenty years of random killings don’t shock them into common decency and sane gun control, why would photographs of the attacks – and so what we’re really talking about is bringing in a new group of legislators, swaying the electorate through shocking enough images that they vote in Democrats in the midterms. That brings the graphic images debate into the same category as the ‘resistance’ press in the aftermath of 2016 – with the premise that core national values had decayed to such an extent that the press in turn had to abandon certain enshrined protocols, in the case of 2016 the attempt to be ‘balanced,’ in the case of the graphic violence debate the effort to be decent. I’m not necessarily a stickler for the press being non-partisan – that’s generally an illusion and often means defaulting to the status quo – but I saw the damage that the ‘mainstream media’ did to itself while endeavoring to challenge Trump’s legitimacy and I have the strong suspicion that the publication of graphic images means the continued collapse of a moral high ground, the New York Times moving inexorably in the direction of the tabloids.

I find it odd and unsettling that I’m arguing essentially in favor of censorship – a regime of ‘decency,’ of editorial desks choosing to not publish certain photos. For the last couple of years, I’ve been really ballistic about censorship in the press and online, the media and the platforms snipping away viewpoints that run counter to accepted taste – and even more upset about a de facto censorship within art, the arts bureaucracy judging work through politics and morality and sidelining work that’s aesthetically bold. So I have to do some work within myself to argue for why Lapvona is basically ok and why Joshua Katz should be able to write whatever he wants to on Quillette but the AP should sit on certain photos coming out of Uvalde. At some level, of course, I really don’t want to see these images, which are, by all accounts, scarring. All week I’ve been averting my eyes from the news crawls on my phone, which keep insisting on showing me the face of the Highland Park killer. And I know from experience that visceral photographs aren’t really a spur to action – they tend to numb, to stupefy.

That’s all personal experience and intuition, but I think I can frame that in more logical terms. A newspaper or news agency holds a certain conception of civil society – e.g. ‘all the news that’s fit to print’ – and guards against incursions of those values. Nick Ut’s ‘napalm girl’ photograph mattered because it documented a napalm attack carried out by a U.S. ally and featuring U.S.-made chemical weapons, the photograph of the Syrian toddler drowned on the beach in Turkey mattered because the Syrian civil war had fallen through a gap in international news coverage. Mass shootings – which, from this perspective, are a form of terrorism – are a very different event. They are not carried out by the powers-that-be. They are enacted by people who have moved outside the bounds of civil society and who are intentionally trying to create as much harm as possible in that society – above all, through notoriety, through manipulation of the news cycle. The normal journalistic concepts of accountability, of speaking-truth-to-power are irrelevant. Mass shooting events are, simply, an exercise in evil, and the documentation of them – through photos of the scene, photos of the killers – is, even when carried out with the best of intentions, a means of allowing the spread of evil.

Now, there are modes for grappling with evil within civil society and for achieving some kind of catharsis. Art has a very significant role to play here. All kinds of great art – David Lynch movies, Céline novels, for that matter virtually any thriller or mystery – is about getting close to evil, listening to it, understanding the way evil works in oneself, and, in theory, defanging it. But this is a very delicate, very ritualistic process – the lights are turned down, a large group of people becomes quiet, a protected space is created for collective dreaming, for the play of the subconscious. And journalism in its way is part of the civil society’s process of confronting evil and healing from it – through the hand-wringing op-eds, through the ritualized phrases, through the very process of writing about horrific, traumatic events in the detached tone that lets you know the world will keep turning no matter what, and every so often in the shock therapy of documenting a really grisly event. But terrorism and mass shooter events are designed specifically to overpower society’s ability to grapple with evil. They ask for attention, they sow confusion. A newspaper printing the very worst of images of a shooting is, in effect, giving up its role as a social protector and turning the narrative over to terrorists – and, in this case, for the sake of a fairly short-sighted, tactical effort to influence GOP legislators (or, really, the voters with power over the GOP legislators) to enact meaningful gun control reform.

I suppose that having a Jewish background makes me comfortable with the idea of prohibitions on certain kinds of images and knowledge – in Judaism, notwithstanding the traditions of unending inquiry and skepticism, there are the prohibitions on saying the Lord’s name or looking on the Lord, the drowning-out of the name of Haman, the circumspection that surrounds the destruction of the Temples, the Fackenheimian prohibition on ‘granting posthumous victories to Hitler.’ There is a very deep understanding – which is echoed of course in other religious traditions – that there are things that mortals should not know, that transparency is a limited virtue. J.M. Coetzee includes an involved debate on this in his novel Elizabeth Costello – the question of whether there is a limit to what art can depict – and concludes that there is, that scenes of extreme torture, for instance, belong behind the veil. And that’s within art and religion, highly ritualized practices which human beings enter into voluntarily and with some in-built degree of spiritual counseling. A photo above the front-page fold of a newspaper is very different – there’s no protection there, there’s no ability, really, to turn away. The direct result of having evil displayed in a newspaper or on TV is, simply, to have evil radiate around the society.

What fun politics used to be!

Everything about the demise of Boris Johnson feels so quaint, so of-a-different-era, like it could be snatched out of an Evelyn Waugh novel. This week’s news has really made me regret not reading more Johnson’s various scandals while they were happening – just so juicy! so refreshing! – and gives me the feeling of tuning into a TV show that everybody else has already watched.

To recap – each of his scandals has been tawdrier and more simple-minded than the one before: the £100,000 of government money he spent on a pair of paintings for 10 Downing Street, the irresistible urge to go partying – the popping crates of bubbly while everybody else was on lockdown – the case of the conservative MP caught watching porn while in the parliament back benches, the case of the Whip whose habit of getting drunk and groping MPs seemed never to inhibit his career. Each of these scandals is like a lost art – the inane act, the requisite popular outrage, the blubbery defense, the equivocating Party condoning everything until they finally can’t anymore. Best of all are the excuses – the MP confessing that one of the porn-watching incidents was ‘a moment of madness’ but claiming that the other was a link he’d accidentally clicked while attempting to watch a video about tractors!; the Deputy Chief Whip starting his formal letter of apology for one of his many groping incidents with “I drank far too much last night,” which was apparently just the right note to hit with Johnson who got it and let bygones be bygones. And best of all are the names, like in a Trollope novel where every character’s name matches the act they perpetrate – just the sheer gift to us all that not only is the key witness Alex Story but the groping Deputy Whip really is named Chris Pincher. (And the poetic justice of it appealed to Johnson as well and is what, ultimately, seems to have undone him – “Pincher by name Pincher by nature” was Johnson’s comment and, apparently, he just didn’t have the heart to fire him.)

Johnson’s fall probably is the first time I’ve really laughed in a while, or really enjoyed the news – a ridiculous, inconsequential person brought down by ridiculous, inconsequential scandals. It’s a reminder also of what I had in mind when I voted for Biden over Bernie – the return of normal, the return of boring. I am, actually, eager to hear more about Hunter Biden’s financial scams, about the Ashley Biden diary that the FBI may well be covering up – stories that the mainstream media has absolutely blanketed with silence. All of this is the coin of democratic politics as we’ve become accustomed to it – scandal, the humiliation of prominent public figures, the perp walk when the public figures can no longer talk their way out of it. It’s interesting, in the saga of the endless forgivability of Boris Johnson, that even his humiliation and disgrace are somewhat lovable (at least to me; granted, I’ve never lived under his regime) – he's doing the perp walk from Number 10 as we want it to be done, a bit shambling, very reluctant, but ultimately with a kind of good grace about his own defeat.

The fact that everything about Johnson’s departure has such a retro feel is an indication of just how far politics has moved in the last five or ten years. Most of that has to do with Trump, of course, but it’s a shift that was to some extent engineered by Johnson himself. Basically, both Trump and Johnson cracked a certain kind of political code. Politicians used to feign empathy and sincerity; when they’re caught in corruption or scandal, the real issue is that their empathy is exposed as a sham. Trump and Johnson had the bright idea of bypassing that first layer of bullshit – they didn’t feign empathy at all – and they intuited that with the proliferation of news sources they could get past the gatekeepers and the court scribes and, even if they were written off by the entire establishment, they could still make it as folk heroes, turning the establishment’s opprobrium against itself.

But that is of course not at all to say that Johnson and Trump were bullshit-free. They were encased in bullshit; it was bullshit to a whole other level, bullshit that was greater than the men themselves. Everybody who’s ever known Johnson is really dazzled by the scale of his lying. Rory Stewart wrote, “He’s probably the best liar we’ve ever had as prime minister.” Max Hastings, a former boss of Johnson’s who is as indispensable to British politics as Ted Cruz’s college roommate is to American, wrote, “I would not take Boris’ word about whether it was Monday or Tuesday.” In the end, it was the lying that was really intolerable to the Tories - which is really saying something, that Johnson lies too much to be a politician.

The point is that it was a different variety of bullshit - the politician pretending to be pugilistic rather than the politician pretending to be empathetic. No matter that Trump and Johnson were essentially weak men - Graeme Wood on Persuasion nicely summarizes recent revelations from the January 6th Committee by pointing out that, taken together, they paint a picture of Trump’s deep lassitude, that he spent most of January 6 watching TV as opposed to carrying out the coup that he had fomented, that he might have grabbed the steering wheel of The Beast but then didn’t touch it again after he was reprimanded by his own security people - but nonetheless they were able to give the illusion that they were fighting. The Spectator, Johnson’s old rag, has been my main source for trying to understand Johnson from the inside, and, in their elegy for him, they can’t find any real achievements in his messy, scandal-ridden regime, but they do repeat the central organizing line - that Johnson fought for the working man.

Another article in The Spectator - this one written in 2019 - offers more insight into the Johnson phenomenon. It describes Johnson on the stump of trade shows in the 2000s - brilliant improvisational performances in which he had to peer over his shoulder to see the name of the organization he was addressing, and brought the house down by losing the thread of his own joke right before the punch line. The author of the article - an upstaged speaker at the same event - was beyond-impressed, even wrote Johnson a fan letter for his improvisational skills, until he was paired with Johnson at another event a few months later and saw him do the exact same thing, The discreet look-over-the-shoulder, the forgotten punch line.

In other words, Johnson was a ham doing very broad standup comedy. And Trump was essentially a standup comic as well - maybe not a great one, Larry David sniffed that it was like a bad Borscht Belt routine, but he definitely landed more laugh lines than Hillary Clinton or Joe Biden. At the level of archetype, it’s as if - at least for a moment - we replaced the old archetype of the politician as priest or as wise counselor with the archetype of the politician as standup comic, with emphasis on rude truths, on playing to the gallery, and on heightened awareness of the performance itself. That’s part of a very powerful social shift - I’m remembering in the 2000s how everybody I knew got their news from Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert, and around that time I was leaning on Louis C.K. and Doug Stanhope for my social commentary. There was something very natural about standup drifting into politics - and it may have just been an accident that it became a tool of the right, that the liberal parties retained a greater degree of decorum over modes of political exchange, that the gifted sociopaths came from the right. So – even aside from Trump – I’m very doubtful that there is a return to normalcy, that Boris Johnson’s fall presages some nostalgic reawakening of qualities of shame and reproach. The archetype of the politician’s role has shifted dramatically – and much faster than the liberal parties seem capable of responding to. It’s not really the healer or the mediator. If it’s not necessarily the standup comic, then it’s at least the putative fighter, the gifted performer of self-image.

Out with it. I’m not ‘anti-vax’ in the sense that I fully accept that vaccines provide a better outcome for positive Covid cases and seem to be generally safe. But I am livid at the incursion of civil liberties that occurred with the vaccine rollout in 2021 – the effort to squeeze the unvaccinated out of public space (no access to shops or restaurants in various metropolitan areas, mandates within schools and places of work) and the rigorous censorship of any voices of dissent that criticized the vaccine protocols.

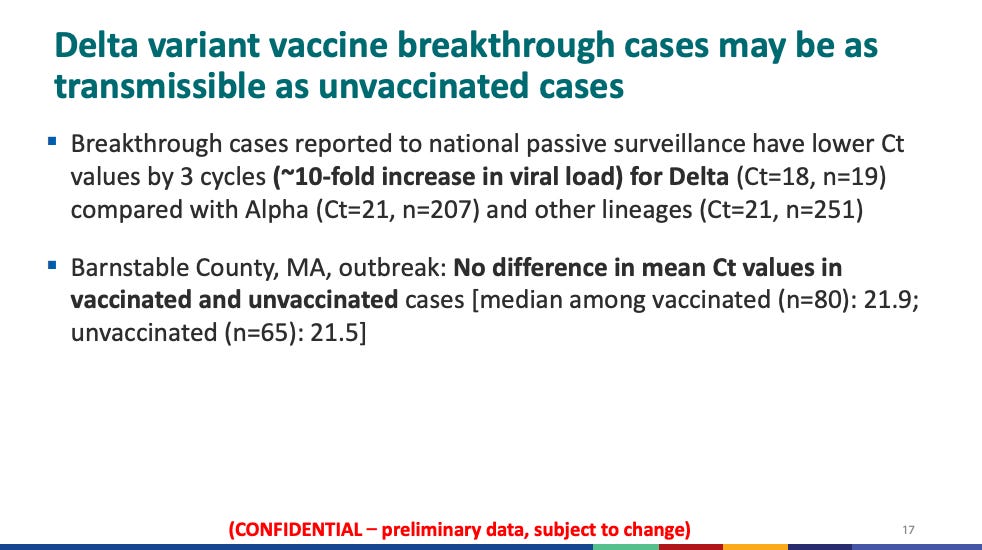

These restrictions continued long after the initial justifications for them had faded – when it was clear (per leaked CDC data as well as statements that the vaccine manufacturers had made from the beginning) that the vaccines had very little impact on transmission and even after the virus had mutated and ‘breakthrough’ Omicron cases became routine for the vaccinated.

I’m sure I’ll have lots more to say about this – it’s a very sore subject for me. At the moment, fortunately, the peak-insanity of mass vaccination seems to have passed. The vaccine card programs have wound down. There’s even – very tepidly, if you know where to look for it – some acknowledgment in mass media that the vaccine rollout didn’t quite go as planned, that the boosters, the delay in approving the shot for the 0-to-5 age range, the ‘breakthrough cases,’ the mutation to Omicron and the redundancy of the initial vaccines are all indications of failure. Sooner or later there will be the serious, intelligent books and articles questioning aspects of the pandemic response – the CDC’s withholding of critical data, for instance, or the ‘waning effectiveness’ of the initial vaccines – the sort of diligent reporting that accompanies every other globally-significant event and that was so conspicuously lacking in the mainstream media through all of 2021.

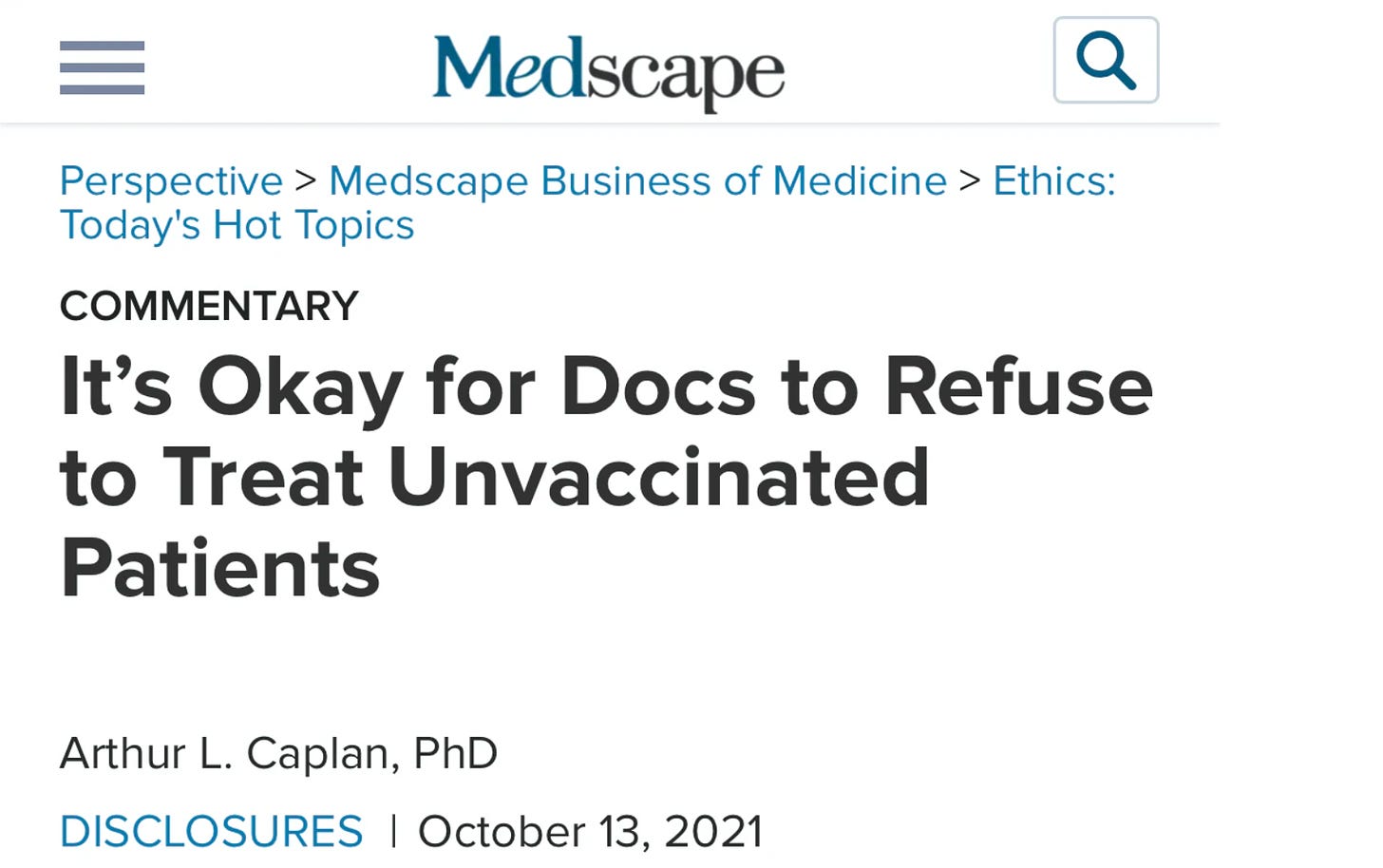

So a chance that things get back to normal – the press remembers its obligations to question narratives pushed by the government, let alone by major pharmaceutical corporations; society emerges on the far side of the pandemic and learns to live with the mutated, increasingly non-lethal strains of Covid. But there is still a reckoning to be had with the curtailment of civil liberties all through late 2021. The much-canceled Alex Berenson has a terse, eloquent article on this on his Substack. The real hurt here is that the censorship and ostracization were carried out above all by liberals – by the sort of people who I know very well, who I consider to be my people, and who had spent so much of their lives advocating for freedom of speech and of expression, for autonomy over one’s body, for the importance of dissent and of open exchange within the body politic. It was a bit stomach-turning to see New York Times columnists and good liberals run irate columns about some school board in Tennessee banning Maus at the same time when journalists and medical professionals were being kicked off social media platforms for questioning the vaccine programs, when Senate hearings were being stripped from YouTube for including Covid ‘misinformation,’ when the same op-ed pages were celebrating the boycott of Joe Rogan for hosting vaccine skeptics, when the 30% of unvaccinated Americans were completely unheard from in the mainstream press. And it was something more than stomach-turning to see venerable institutions – newspapers-of-record – gloating (there really isn’t another word for it) when somebody unvaccinated died from Covid or seriously questioning whether the unvaccinated deserved medical care.

The cognitive dissonance here is so powerful that I don’t expect liberals to grapple for some time, if ever, with the ethical ramifications of having, for a period of time, created a caste system and of assiduously suppressing an open conversation about it – and to have done so for the already-indefensible excuse that the unvaccinated were allegedly more contagious. To be fair, coverage in the mainstream media was so categorical in its adoption of the orthodox narrative of the vaccine rollouts and in its castigation of the unvaccinated as being far-right or Trumpy or anti-science – which was not at all the case – that I think a tremendous number of liberals didn’t even realize that there were debates on the wisdom of mass vaccination within the medical world. But what is galling is see the same lack of awareness continuing now. NPR has a story – written ‘in partnership’ with the Kaiser Medical Group, which of course tells you something – expressing fury that opponents of vaccine mandates would appropriate the sacred ‘My Body My Choice’ slogan from the abortion movement. The NPR article beats around for a while trying to come up with a reason why the extremist anti-vaxxers would possibly appropriate a liberal slogan – and the interpretations offered are either that’s a bit of mischief or that it’s savvy partisan politics, “one side’s base adopting the slogan of the other side’s base,” as a Democratic strategist quoted in the article puts it. What NPR – or, I guess, it’s more fair to say Kaiser posing as NPR – doesn’t even consider is the possibility that, actually, abortion rights and the right to remain unvaccinated are, on the level of civil liberties, the exact same issue. Once it became clear that the vaccines were effective against outcomes but not against transmission – as was clear, if not widely reported, by the summer of 2021, through statements by the Moderna CEO, through leaked data from the CDC, through data from Israel’s vaccine rollout, through the prevalence of ‘breakthrough cases,’ and then became screamingly obvious by the winter and the appearance of Omicron – the logical argument for compulsory, or coerced, vaccination faded completely. There was still – and is still – a perfectly viable argument that vaccination is the right personal decision to make, but, on the level of civil liberties, that’s the exact same argument as an outside entity telling a woman that she has a moral responsibility for bringing a pregnancy to term. Individual choice predominates over the moral calculus of anybody else – whether that’s the government, health agencies, religious authorities, etc. Accept that line of reasoning for abortion – as most liberals do, and as I do as well – and it’s very difficult to reject it for vaccines. Odd that NPR – or Kaiser – somehow can’t even think about it that way.

Ok fine.

Don't know if I'm with you on the vax stuff but definitely down with Blow!