Commentator

Russian Soldiers Kvetch, That Orgo Class, Twitter-Dorsey=Musk, Vaccines and Periods

THE RUSSIAN SOLDIER SPEAKS

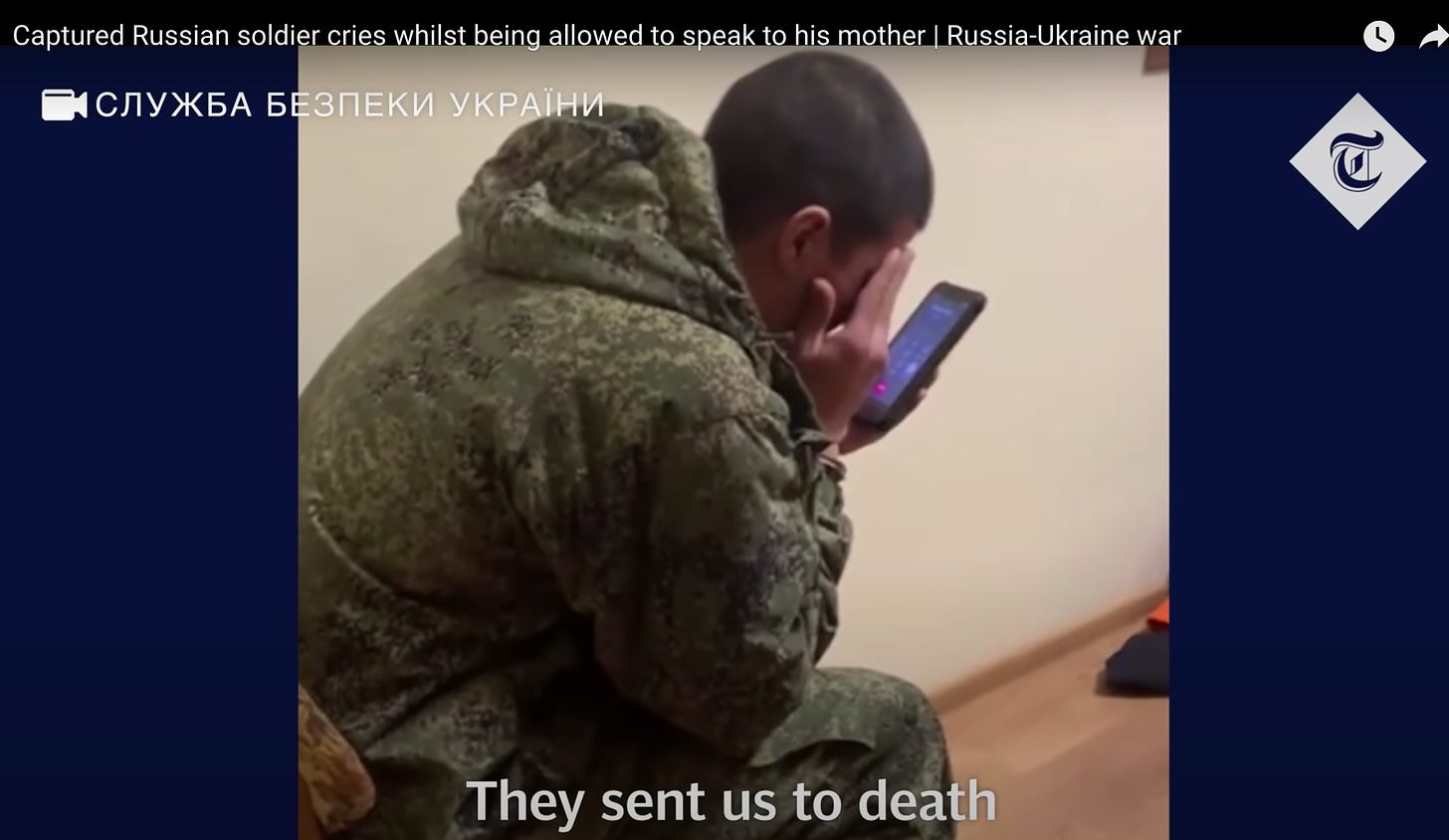

It really is bracing to listen to phone calls from Russian soldiers in Ukraine calling their families. There were a series of videos released early in the war by Ukrainian authorities of Russian POWs calling home. These all felt authentic enough but were of course impossible to verify given that the Russians were already in captivity and the Ukrainians releasing the videos as war propaganda. A haul of audio recordings taken from the same period of the war - the Russian assault on Kyiv in March - is a more reliable snapshot of what’s really going on for Russian soldiers, with The New York Times separately corroborating the recordings.

And the overall picture is overwhelmingly of a piece - the story of the war is the really pathetic state of Russia’s military combined with a startling disregard by Russia’s leadership for the lives of its own soldiers. Russian units have been poorly led, poorly supplied, badly demoralized. Russian military strategy involved cheap tricks like confiscating soldiers’ cell phones to keep them from calling home, like telling soldiers that they were on training exercises right until the moment that the Ukrainians were shooting at them.

The voices of the soldiers have a certain dignity to them - of people caught in a trap and speaking, with clarity, of the reality of what they’re facing. “We were fucking fooled like little kids,” says one. “You should see the way we look,” laughs another. What’s most bracing of all - more so than their evident demoralization, more so than the feeling of listening to the walking dead who might be killed any moment - is the incredulity of their interlocutors, particularly their parents, who clearly are having a great deal of trouble choosing between two very different realities, the reality of what they see on state TV every day and the reality of what their own children are very forcefully telling them. “Seryozha, you can’t be so one-sided. I understand that it’s scary there and you can’t be one-sided,” says one mother, in her most reasonable tone, in what may be the most difficult call to listen to from The Times’ article, which makes Seryozha really lose it and tell her, “What does scary have to do with it? We all think the same thing. The war wasn’t needed.”

This is not at all just a Russian phenomenon - it’s the result of being in any sort of closed society with access to a limited amount of information. There’s an excruciating chapter in Gabriel Chevallier’s Fear in which the narrator, a French soldier in World War I, visits his father on leave and, by the end of seven days of the chit-chat of the father and his drinking buddies, basically can’t wait to return to his trench where at least he’ll have some dose of reality. And same goes for the U.S. comprehension of the Iraq/Afghanistan wars especially in their Jessica Lynch phase - just a complete inability to understand the helplessness and the brutality of the experience of front-line soldiers.

The lesson here is the diabolical effectiveness of wartime propaganda within enclosed information systems. The father in Fear can’t understand his son precisely because he is reading newspapers and because he forms his fixed ideas of what the war must be. The Iraq and Afghanistan wars seemed not so terrible precisely because we were watching them on television and thought we understood. When I was in Ukraine, there was a certain perverse reverence for the control that Russian state media had over the population. “The propaganda works perfectly” I was told. And it’s a bit of a myth that the painful reality of front-line soldiers can ever fully puncture something like that. It took years after the end of World War I for a novel like Fear even to be published. America hasn’t really come close to grappling with on-the-ground truths of the ‘War on Terror.’ I’d fully expect the reasonable tone of Seryozha’s mother to prevail for the foreseeable future.

From a more philosophical vantage-point the takeaway is about the vital importance of media. Russia, for most of Putin’s regime, didn’t feel like a Fascist country. It wasn’t a police state, there was always some regard for ostensibly democratic norms (the fact of elections, for instance). But the dissemination of ‘news’ was along very narrow lines - and increasingly narrow the further down one moved on the socioeconomic ladder - and that, really, was the origin of the Ukraine war, the ability of government to shape reality for its population right up until the moment when conscripted soldiers on ‘training exercises’ found themselves under fire. And that’s something to be very alert to in Western ‘liberal’ countries as we deal with a certain narrowing of our news, as social media algorithms become increasingly potent, as news-gathering gets increasingly institutionalized and consolidated.

And from a more immediate tactical vantage-point the takeaway is, again, about just the bottomless ineptitude of Russia’s approach to the war. The Intercept has an intriguing piece reporting on the CIA’s complete misanalysis of Russia’s military prowess at the start of the war. Essentially, the CIA shared Putin’s own assessment - that “Russia would win in a matter of days by quickly overwhelming the Ukrainian army,” as The Intercept writes. What the CIA, the Kremlin, what everybody missed, was the true extent of corruption within the Russian military. The person who spotted this most clearly was Navalny. The overriding point of his videos wasn’t so much that Putin was autocratic - although there was that - as that Putin’s state was built entirely on corruption, a power structure that worked wonderfully well for pillaging resources but not at all for any sort of administration or governance. But, unfortunately, Navalny was a lonely prophet, now imprisoned. And that canary-in-the-coal-mine voice switches to the Russian soldiers on the front-line saying in their quiet way, “Fucking higher-ups can’t do anything.”

FOREGO ORGO

Everybody’s up in arms about the N.Y.U. organic chemistry class - as The New York Times accurately notes, “This one unhappy chemistry class could be a case study of the pressures on higher education as it tries to handle its Gen-Z student body.”

And, as usual with these sorts of controversies, everybody’s actually talking about a variety of disparate issues. The main points are: 1.the last stand of teaching as a profession - the century-and-a-half-long shift of teacher as lord-and-master of a classroom with the capacity to administer corporal punishment at will to a ‘customer service’ model in which the teacher is answerable ultimately to the ‘well-being’ of students, as the class petition put it; 2.the general collapse of education standards particularly as a result of the pandemic; 3.the sense of Generation Z as hopeless crybabies, grade-grubbing turned into some sort of personal right.

I’m sympathetic to all of those points, although, in this particular case, the real issue strikes me as being something a bit different. The difficulty is that Matiland Jones Jr. - the professor in the hot seat - is essentially serving two very different masters. His nominal employer, with hiring-and-firing power, is New York University, which has its obligations to undergraduates’ ‘well-being’ and is suffused with institution-wide grade inflation; and his real employer, at least as he saw it, was the med schools and their weeding-out process for potential applicants. Everybody involved in the controversy understood it in those terms. “Students protested that they were not given grades that would allow them to get into medical school” is how a different N.Y.U. chemistry teacher summarized the controversy for The New York Times.

What the controversy revealed, then, was a rift in the mission of an undergraduate college. For most students, in the liberal arts wing of the school, their grade point average, let alone their grade from a single course, doesn’t matter all that much - they have a variety of potential careers ahead of them. For the pre-meds, though, ‘liberal arts’ is a facade and N.Y.U. basically a vocational school and one disastrous D or F grade really can be a career-ender. And, from that perspective, the students had a point - a single tough teacher like Jones simply exercised too much power over their futures. And, seen as part of vocational school, the fact that the students were evidently slacking off is neither here nor there - N.Y.U. had a certain vested interest in getting its pre-meds through undergraduate with a high enough GPA that they could qualify for med school, and Jones’ unduly tough grades were a disservice to the university as a whole, meaning (in theory at least) that the college would produce fewer doctors, which would result ultimately in a dip to the endowment, etc.

The real solution to the problem is well outside the scope of this particular controversy. It’s a recognition that the modern American university serves a variety of very different functions, which are ultimately not at all compatible. This is most famously the case in student athletics, which, really, is a way of installing semi-professional sports teams on campus without paying them and to the detriment of academic life as a whole. But it’s the case as well in pre-med programs, which are their own kind of fiction - the premise that the pre-med students are benefiting from the same sort of liberal arts education as everybody else when the reality is that course load requirements, and the pressure of career-defining sink-or-swim classes, drive the pre-med students into a completely different educational experience. The real solution is something closer to the European model of early specialization - let the athletes be athletes; let the doctors be doctors - but nobody wants to openly move in that direction because the fiction of the liberal arts college serves its own purpose, conferring a marketable degree and status-badge on students from a particular university irrespective, really, of what they actually learned during their education.

But, as a symbol, the Matiland Jones Jr. story comes across very differently. He becomes the John Henry, or at least the Bill Stoner, of higher education, holding to some ancient vision of the teaching profession - the teacher faithful to the integrity of the subject matter and with dominion over the classroom, heedless of the whingeing of the students and parents and of the craven conformity of the university itself. It is a very attractive image - Bill Stoner marching to the head of the class and teaching medieval rhetoric (his subject) in place of the freshman composition course foisted on him by a departmental rival - but in this case it doesn’t exactly apply. Jones is very much part of an industry - the process by which N.Y.U. ferries its pre-med students through to med school - and it’s a bit silly to pretend that he serves the interests of pure medicine. If N.Y.U. thinks he’s flunking too many undergrads, then, ipso facto, he’s flunking too many undergrads - medicine long ago became a vocation rather than a calling. If we have a problem with that structure (and probably we should) then there’s a great deal more to change than just the standards in one class.

TWITTER CIVICS

I haven’t been paying attention to Elon Musk’s Twitter acquisition for three perfectly good reasons: 1.I can’t stand Twitter; 2.I don’t think it ultimately makes much difference who owns it; 3.It seemed as likely as not that Musk would renege on the deal. But Musk’s buying-it/not-buying-it/maybe-again-buying-it saga is inescapable, and the recent unveiling of his text messages as part of a court discovery process is just too fun an event to not talk about.

The Atlantic has an entertaining piece by Charlie Warzel claiming that the texts “shatter the myth of the tech genius.” Warzel quotes a tech executive saying, “There’s no real strategic thought or analysis. It’s just emotional and done with no real care for consequences.” And Warzel gets in his best line by writing, “Whoever said there are no bad ideas in brainstorming never had access to Elon Musk’s phone.”

But from the texts I’ve read (the same ones being cited by everybody else) it’s really not as bad as all that. It’s just not possible to make a $44 billion deal through ‘strategic analysis’ - it has to turn on ‘emotional’ decision-making and a gut call since, ultimately, Musk is betting on the whole direction of history, on whether Twitter will continue to be as relevant to public discourse as it is now.

The surprise for me, really, is how philosophical the texts get. Far more than Musk, Jack Dorsey is the interesting figure of the text logs. His mea culpa to Musk - “[Twitter] should never have been a company….That was the original sin” - is such a startling repudiation of the last decade of the Internet’s development that it’s remarkable that it hasn’t been more widely reported on.

Dorsey’s message points in the same direction as the argument of Chris Hughes, the Facebook co-founder, that the major social media companies really need to be treated as public utilities. That would seem to lead - in the ancient progressive tradition - towards some sort of dispassionate governmental control, but it’s completely clear that government has nowhere near the power or wherewithal for an antitrust play in social media. Instead, it’s left to such unexpected social philosophers as Elon Musk and Mathias Dopfner, the Axel Springer CEO, to attempt to wrest Twitter back from narrow-mindedly corporate control and towards some renewed sense of its societal role. “Solve Free Speech,” writes Dopfner ambitiously as the first step of his ‘business plan’ - which involves recognizing that Twitter is “the de facto public town square” and is subject to some kind of higher law than the profit motive.

For Warzel, a business plan like “Solve Free Speech” is automatically disqualifying and shows by itself that Dopfner is “woefully unprepared for the task [of running Twitter].” But that’s The Atlantic, which tends to be pro-Big Tech and to default to left-of-center establishment thinking. Musk, Dorsey, and Dopfner are actually being much more interesting than that. There’s a libertarian slant, of course, to Musk’s thinking, but Dopfner’s typo-ridden text reads as if he’s a Constitutional ratifier. “Make Twitter the global backbone of free speech, an open market place of ideas that truly complies with the spirit of the first amendment,” he continued.

And why not? That approach to public discourse has worked perfectly well over two hundred years of American history. Leave it to a German publishing magnate to make the argument that the U.S. Constitution can be a better guide to discourse than Twitter’s current ornate Terms of Service.

I have no idea how viable Musk’s takeover bid really is - if his group can deal with the bots problem, is serious about eliminating censorship, and can actually earn their money back from the Twitter purchase. (Curiously, Musk’s interlocutors tend to be very bearish about Twitter’s long-term prospects - “there no structural growth…no confidence in the existing business model,” Dopfner wrote.) But the point is that Elon Musk and his cronies turn out, surprisingly enough, to be much more high-minded and philosophically-attuned than, for instance, The Atlantic. The assumption from the media is that all of this is business-as-usual. And it’s the tech titans themselves who seem to have a greater awareness that tech is creating a social dystopia - that the algorithms, the ad revenues, the content moderation are bad news, that the companies need as much as possible to get out of the business of controlling the public sphere and to treat a space like Twitter as what it is (or should be), a utility, a public good.

FACT CHECK: VACCINES AND MENSTRUATION

A new study shows that yes, Covid vaccines do in fact affect menstrual cycles. This was kind of the first feedback on the vaccine - women widely reporting significant changes in their periods shortly after receiving vaccine doses. And, particularly in liberal circles, that might have been expected to generate heightened scrutiny of the vaccines given the perennial emphasis on believing women’s stories and granting autonomy to women’s bodies. And those are absolutely, unequivocally, the top priorities except, you know, in the case of the vaccine roll-out.

Now, a year later, after however many coercive vaccination measures, the mainstream publications find themselves very carefully walking back what they said at the time and conceding that the many women presenting “anecdotal” information about their periods may actually have been exactly right all along. “New research shows that many of the complaints may have been valid” is The Washington Post’s summation of the study.

For people who’ve been ‘vaccine-hesitant’ or ‘vaccine skeptics’ or whatever you want to call it, it’s incredibly refreshing to read a simple sentence like that from The New York Times or Washington Post or in any of the major medical journals. Alison Edelman, lead author of the BMJ Medicine paper, was more forceful than any of the newspaper reporters and said, “We hope our findings further validate what so many individuals reported experiencing.”

The point I’m making is that we may, at long last, be entering a phase in which we’re able to talk about the pandemic like grown-ups - in which competing narratives are aired out in public space and in which uncomfortable data points (like the correlation of vaccines and changes in the length of menstrual cycles) are entered into ‘the public record’ even if they contradict more congenial narratives from health authorities. That’s not being alarmist - in any case, the findings from the BMJ Medicine study indicate that periods “tended to return to normal” after a single cycle - but it means that it was naive to think (as the health authorities kept assuring us) that the mRNA vaccines were completely safe, with no side effects whatsoever. Simply put, it was way too soon to know anything definitive about the effects on period cycles at the time of mass vaccination just as it’s too soon now to say anything meaningful about effects on fertility. For the ‘vaccine-hesitant,’ who found it so difficult throughout 2021 to have a hearing in anything resembling mainstream forums, that was always the point, no more no less - we don’t know, it’s too soon to say. And now, with the coercive measures waning, there’s some belated recognition that, yes of course, real science takes time to do its work and can yield all sorts of surprises.

I’m saying we may be able to talk about the pandemic and the vaccines like grown-ups, but that’s still a bit of a ways off. The reports on the BMJ Medicine study are weighted with all sorts of unwarranted caveats. “Experts say there is no indication that vaccines affect fertility” is The New York Times’ sub-heading for its piece - which, actually, is a ridiculous thing to write and the opposite of journalism. The study simply wasn’t about fertility, it was about menstruation. It’s true that there was ‘no indication’ of an effect on fertility - that’s a direct quote from Edelman - but only because fertility wasn’t being tested. For The New York Times to write that as a headline for the story is deceptive and part of the ongoing campaign of using the form of journalism to, instead, provide reassurance.

And the mainstream publications are, not surprisingly, engaged in a bit of CYA with regards to their own initial coverage of the widespread concerns around menstruation and fertility. The articles now make the point that you would expect them to make - that menstruation is a “neglected topic” in scientific studies, as Science writes, or is “woefully understudied,” as Edelman puts it. But a quick scan of some articles on the subject evinces a degree of bad faith from the mainstream publications. “No, We Don’t Know If Vaccines Change Your Period” ran a New York Times headline in April, 2021. “Misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines impacting fertility has been one of the most persistent myths during this pandemic,” said the U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy in February, 2022, as cited in the American Medical Association’s JAMA Network. “[The vaccines are] injected into your arm, and that’s where they stay….they can’t spread,” said Johns Hopkins epidemiologist Jennifer Nuzzo in April, 2021, as quoted in a New York Times piece called ‘No, other people’s Covid vaccines can’t disrupt your menstrual cycle.’

All of this is classic straw man argumentation. Infertility from other people’s Covid vaccines is far-fetched, but that’s not really what most people were worried about. “The related concern that getting vaccinated [oneself] could affect menstrual cycles is….theoretically possible,” mumbled The New York Times piece towards its end, “but anecdotal reports could be explained by other factors, and no study has found a connection between the vaccine and menstrual changes.” Never mind that that incidental “related concern” was the real concern - and that “no study had found a connection” because, at that time, there were no studies on the subject.

Now that we do have some actual studies in, the cavalier attitude of 2021 and the vaccination roll-out becomes badly exposed. “Researchers don’t know exactly why the vaccines seem to affect menstrual cycles,” writes The Washington Post now, which is a perfectly reasonable thing to say - and very different from Nuzzo’s “The vaccines are injected into your arm, and that’s where they stay….they can’t spread,” which was an unverified statement at the time and is now clearly shown to be false.

Wide ranging and fascinating, including a novel high on my list: _Stoner_ by John Williams--love the beginning when Lear gets quoted and that just for starters. Thank you and xo. --Mary

Let me understand what you're saying on the orgo class? You're saying a pox on medicine because it's too vocational but since Jones is in the system he has to abide by it? You do get subtle sometimes.