Well, what can I say about Dobbs that hasn’t been said already?

A few impressions:

Dobbs really is the end of an era. To a startling degree our political life has been about re-legislating the 1970s - and, now, a certain Counter-Revolution is nearly complete. I’d be really shocked if Thomas gets his way and contraception (!) is next to fall while the sodomy laws go back on the books, but affirmative action rulings seem very unlikely to survive this court while same-sex marriage is looking really precarious.

Roe was a linchpin keeping our political process (to some extent) intact. Abortion is hot-button enough of an issue that it can scuttle any legislative progress. To have had it ‘settled’ by the courts meant that some bipartisan fabric was possible. To have it thrown back ‘to the people and their elected representatives,’ as the majority opinion sunnily puts it, means probably a generation’s-worth of legislative and litigious battles. I remember working as a field organizer for a Democratic senator, talking to a voter at some state fair sort of event and being told, “I’m not going to vote for Senator N-. Senator N- kills babies.” At which point - as eager as my campaign was for every possible vote - I could turn around and walk the other way: it was just a given that abortion was off the table politically. And as of Friday, if I were in the same position, I would likely have to engage with that voter on an inherently impossible subject: Senator N-, in a battleground state, would have some temperate position on abortion, and the election would likely turn (like many elections to come) on inflamed debates about abortion rights, which means also inflamed debates about the role of religion in public life. I’m fully expecting that, particularly in battleground states, our political fabric will start to fray in a way that’s not so dissimilar to the disintegration of the American political process in the 1840s and ’50s. The warning of the dissent that “the challenge for an American woman will be to finance a trip not to New York or California but to Toronto” is a very clear allusion to that period, an admission, together with the dissent’s claim that the court has all-but-lost its ‘legitimacy,’ that the federal government is no longer capable of offering any sort of unity.

Writing from a Democratic perspective, there are a couple of (very slender) silver linings. Both Trump and McConnell have acknowledged that, politically speaking, the Republicans may have overplayed their hand now that they’ve done the full Gilead. Trump lost the suburbs in 2020 and his ‘problem with suburban women’ may well be exacerbated by Dodd. With his reptilian political sense, Trump knows that partisan politics depends on an Other - and it is hard to come up with a more despicable-sounding villain than a party that is willing to control a woman’s reproductive system but not the inalienable right to carry an assault weapon. And - also on the (negligible) plus side - Democrats are forced to give up on a comfy habit of looking to the courts for authority. That was the mindset - a holdover from the now-buried progressive courts of the ‘60s and ‘70s - and, at some subconscious level, it probably prevented Democrats from taking legislative politics as seriously as they should have. There is no reason, for instance, why ALEC should be exclusively a right-wing phenomenon. Now that the abortion fight moves to the legislatures, it’s not impossible to imagine (although it never actually works out this way) a generation of idealistic leftists skipping out on law school and instead running for local office.

The opinions themselves make for remarkable reading - just a step above name-calling among the justices. And now that Originalism is the law of the land - a hard-to-believe thing to write in a sentence in 2022 - it would seem to be important to grapple intellectually with it, if only there were any content there. In the majority’s opinion, Originalism makes its appearance as a cartoonishly folkish and calcified philosophy, locking into the legal system the political attitudes that happened to prevail at the time of ratification of the Constitution or of one of its amendments. “An unenumerated right must be deeply rooted in this country’s history and tradition before it can be recognized as a liberty” is the most Fichtean line in the majority opinion, accompanied by the conclusion “that the dissent cannot establish that a right to abortion has ever been a part of this nation’s tradition.” To which the dissenters can barely even sputter out a response - that fifty years of Roe and the jurisprudence that emanates out of it somehow do not count as ‘history’ or ‘tradition’ and that ‘history’ seems to end, conveniently enough, at a moment in time before women had any political voice. “Either the majority does not believe its own reasoning or else all rights that have no history stretching back to the mid-19th century are insecure,” fulminates the dissent.

The answer, as of course the dissent is well aware, is that the majority does not believe its own reasoning - that the case law it cites is “window-dressing” and that “the court reversed course for one reason and one reason only, because [its] composition has changed.” Alito’s assertion that “the right to abortion destroys an ‘unborn human being’….and distinguishes itself from the rights on which Roe and Casey relied….and does not undermine them in any way” gives the game away. Clearly, the Originalist court is ruling however it wants to rule - freely ignoring any case law that developed over the past 150 years, including two Supreme Court decisions, while citing that great feminist Henry de Bracton who described abortion as homicide in the 1250s. “The majority substitute a rule by justices for the rule of law” is the stark, middle-fingered conclusion of the dissent - and the question now simply becomes how radical the right-wing justices feel like being, with Alito insisting that the abortion ruling is a one-off and Thomas gearing up for rulings on sodomy and contraception (“planning to use the ticket of today’s ruling again and again and again,” as the dissent warns).

What’s lost with the Dobbs ruling - and the dissenting justices are wonderfully articulate on this - is a vision of American jurisprudence unfolding inexorably in the direction of ever-greater justice and equality. “Those legal concepts [embodied in Roe and Casey] have gone far in defining what it means to be an American,” writes the dissent - and that seems right to me. The idea is that there is both the reigning force of law and then, as warp and woof, there is a silent tradition, of those who lack voice, who are brought, in the fulness of time, into the body politic. The Originalist reasoning in Dobbs - to the extent that it can be taken seriously - negates that vision and freezes the rule of law at the time of ratification which just so happens to consign women to ‘second-class citizenship.’ What looms very large here is the failure to pass the Equal Rights Amendment. Not that the right-wing justices couldn’t have found some way around that as well, but the strict Originalist position allows for no judicial movement beyond constitutional amendments and, according to that reading (as was made completely clear on Friday), women still have no role in the constitutional life of the country.

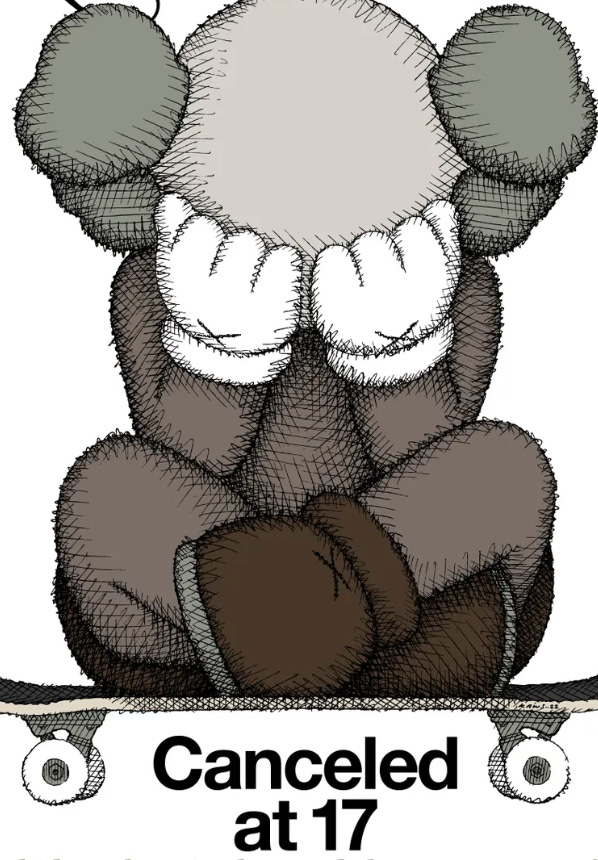

Now we’re deeply in it - the long-awaited Counter-Revolution for #MeToo. This is a very real phenomenon of men, and boys, being summarily ‘canceled’ for some inappropriate sexual conduct that’s well short of assault or rape - and I’m surprised and impressed that New York Magazine would cover it and devote so much anguished space to the story (which, by the way, is much more significant and far-reaching than the primary battlefield for the #MeToo wars, defamation suits and countersuits between celebrities).

It’s worth pairing the New York Magazine piece with this remarkably inane treatment of the subject in The New York Times’ op-ed page - which is roughly like printing an article by some military conscript saying that they plan to be completely unafraid the first time they come under fire. The story that Elizabeth Weil covers is a powerful antidote to Agnes Callard’s declaration of nonchalance - ‘Diego,’ Weil’s pseudonymous protagonist, really does as well as can be expected under the circumstances: he admits wrongdoing, he apologizes, he looks for some form of resolution under his school’s version of ‘restorative practices’ protocol, he keeps to himself, he tries the usual revenge of living well, but none of that is to say that what he goes through doesn’t suck.

The sense I have with Weil’s article - and also Mary Gaitskill’s commentary on the Depp/Heard trial on Substack - is that, at long last, the adults are back in the room. There’s a rediscovered ability, at least in corners of the press, to make gradations for the severity of social crimes. ‘Diego’ has acted poorly, there’s no question about that (he shows off a nude picture of his girlfriend at a party). “Diego really fucked up. Everybody, including Diego, agrees on that,” writes Weil. At a social level, he clearly deserves some sort of punishment, which he duly receives - his girlfriend breaks up with him and stops speaking with him, friends stop having anything to do with him, he gets a reputation as being a ‘bad guy,’ etc, etc. But what writers like Weil and Gaitskill are capable of saying (and what, unfathomably, became heretical for about five years) is that that really should be the end of it. Diego is 17 and has growing up to do. What he did isn’t the behavior of a serial ‘predator’ or symptomatic of ‘toxic masculinity’; it’s an error in judgment by an individual that, to the extent it has to be addressed institutionally at all, should be dealt with at an individual level - he acted wrongly, he makes redress, he’s restored in some fashion back to the community.

But in Diego’s particular case - in the madness of the era of #MeToo and of social media - there is no end to it. Diego’s name is written on bathroom walls on a ‘People To Look Out For’ list, which is then duly Instagrammed. He loses all of his friends - and then his remaining friends are ostracized when they’re seen (and photographed) talking to him. The school claims that his crime is so far beyond the pale that it is not eligible for ‘restorative practices.’ And, with really good reportorial writing, Weil describes how a perversion of #MeToo creates a deep chill in the high school - reifying existing power structures while generating powerful new weapons for further ostracizing figures who are already socially marginal. “I love cancel culture,” declares a school bully, who employs Instagram and the rhetoric of #MeToo to drive Diego into near-suicidal isolation - and does so at a moment when the school itself is too terrified of litigation to even touch Diego’s case. “Students are acting as judge, jury, and executioner for other students,” says the beleaguered principal not long before she herself quits her position.

With the adults back in the room - or at least occasionally able to get nuanced pieces published - it becomes possible to make the following points:

Sex is messy. The rules of sex are not exactly the rules of civil society, and misbehavior within relationships is a different kind of thing from misbehavior against the social order (which is what, at the moment, we’re tending to conflate). Gaitskill is particularly incisive on this point - the ways in which Amber Heard could have voluntarily entered into a relationship in which she was the weaker party and in which she may have fully expected to be exposed to a certain amount of violence. “She somehow got engaged in a power struggle with someone more powerful,” writes Gaitskill. In other words, relationships allow for whole sets of dynamic factors that are not readily explicable in a public forum with clear-cut rules of right and wrong.

Gender is basically a war - and any new tool (social media, the new willingness of the press to publish stories about ‘private lives’) will be immediately weaponized. The right way to think about all of this isn’t so much as a collective working together towards social justice and an inalienably correct code of conduct as it is disparate individuals taking advantage of tactical means at their disposal - Diego misusing the power at his disposal of having a nude picture of his girlfriend on his phone; the school bully corrupting #MeToo rhetoric to gain social power over ‘an abuser’ like Diego; the anonymous writers of the bathroom list driving further terror into the wayward boys of the class.

Public institutions are far-from-ideal venues to handle questions of sexual conduct. The tendency is for everything to flatten out and, in the sexual domain, for everything to become ‘assault’ - which, incidentally, is the safest posture for institutions to adopt against potential lawsuits or a ‘shitstorm’ on social media.

Due process should not be surrendered lightly. In my memory, this really was how we got to #MeToo in the first place. The complaint, around the time I was in college, was that the prosecution of rape was inherently different from the prosecution of any other crime - it put an unfair burden of proof on the victim - and that the way to short-circuit that problem was both to make a presumption of guilt for the accused (“Believe Women!”) and to move the trial out of the courts and into the realm of public opinion. That whole line of thought seemed like a non-starter circa 2010 - as it had when Catherine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin advanced similar arguments in the 1980s - but the specific circumstances of a potentate like Weinstein, who was understood to be beyond the reach of law but whose private life was fair game to the media, allowed for that turn to take place and so now here we are: various ‘shitty media men’ are thoroughly ostracized but so are some uncountable number of collateral casualties like ‘Diego.’ It’s interesting as a side-note that Weil takes great pain to emphasize that, in Diego’s high school, it’s ‘boys of color’ who are disproportionately singled out for accusations of sexual misconduct. And so the logic of social justice swivels around and takes issue with feminism: now that it’s no longer just ‘white men in power’ who are culpable for everything, it becomes acceptable to return to the language of due process and of gradations of guilt.

Olúfémi O. Táíwò’s Climate Reparations

Oh Christ. Climate reparations. I’ve been haunted, since I read it, by a line in Solzhenitsyn’s 1978 ‘Harvard Address’: “It is difficult yet to estimate the total size of the bill which former colonial countries will present to the West.”

With a new social justice theory of ‘climate reparations’ - as laid out, eloquently, by Georgetown University professor Olúfémi O. Táíwò and applauded by Grist - the shape of a possible settlement comes into view, which in turn raises Solzhenitsyn’s corollary question, the difficult matter of “whether the surrender of everything it owns will be sufficient for the West to foot the bill.”

Táíwò’s approach - like some sort of vast class-action lawsuit - skips over the essentially unworkable issue of historical reparations and proposes reparations on a very different, forward-looking basis: as a country deals with the repercussions of anthropogenic climate change, that country is able, in effect, to present the bill to the industrial generators of carbon dioxide who just so happen to be the historical occupiers of that country.

I have to admit that there’s something mathematically and psychologically elegant about that solution - which fits like a key into the guilty consciences of Western liberals. And, like a shrewd arbitrator, Táíwò raises the possibility of settling on a single number and, in theory, an actual payday - instead of dealing with inherently impossible questions like how much is owed for slavery or imperial conquest or the Holocaust, the guilty countries simply look at the tabulation of how much damage is done to an economy through global warming and pay out based on that.

But then, unfortunately, we start to run into the problems. Who exactly is exempt from the charge of imperialism? Are China and India, the countries with respectively the highest and third highest greenhouse gas emissions, entitled to a dividend based on the imperialist past? (Or are they expected to pay out - and what Táíwò is talking about is really just a new way of describing a carbon tax?) And is there meant to be, in whatever mysterious algorithm Táíwò has in mind, a direct correlation between the damage of industrial emissions and the damage of imperial occupation - are leading producers like the United States or Russia expected to pay out to, say, former British or French colonies, countries that they were never occupied themselves? And, since climate change is deemed to be an existential threat and solely the fault of the first nations to industrialize, the bill presented must be correspondingly enormous and ever-increasing, and, as in Solzhenitsyn’s speculation, only abject bankruptcy and humiliation could even begin to cover it.

So a completely illogical and unworkable solution - but that won’t stop it, I predict, from becoming an ever-more central element of political discourse. And to give credit where it’s due, Táíwò’s is a real intellectual achievement. Not only does he consolidate arguments about social and climate justice into a single debate but he moves the debate outside of national borders and makes it an overarching indictment of imperialism: in the half-millennium of the West’s ascendency, runs his argument, the West succeeded in ruining the planet both politically and environmentally. Since the West remains wealthy (although, by Táíwò’s logic of measurable economic impact from global warming, rising temperatures are bound to do a number on the economy of the West as well), who better than the West to cover all the impending damages. And as appalled as I am by the logical leaps here - and the way that a serious-person’s publication like Grist ignores the leaps - I can’t help but be impressed by the symmetry of the equation. No matter that the West rose to power in an era in which imperial sovereignty was the norm and the nation-state a non-existent concept, the West is identified as the sole culprit for imperialism, and imperialism is transformed into a sort of unfortunate Ponzi scheme - the countries that are still recognizable as imperial powers at the moment when their guilty consciences catch up to them are the countries that are left holding the bag and are duly expected to pay out.

I’ve been back and forth in my willingness to engage with John Mearsheimer’s contrarian, realpolitik-driven narrative of the war in Ukraine, but this talk reprinted in The National Interest makes my mind up - Mearsheimer is out of control and is cherry-picking all of his evidence.

Mearsheimer’s view is that everything is great power politics - which means, roughly speaking, the sovereignty of only those countries that have nukes. Ukraine, in that framework, is intrinsically part of Russia’s domain, very much as Canada or really the entire Western Hemisphere would be part of the United States’. Mearsheimer’s contention, made most famously in his 2014 essay ‘Why The Ukraine Crisis Is The West’s Fault,’ is that the United States’ foreign policy post-Cold War was fixated on punishing Russia and on bringing Ukraine into NATO and that, within the iron logic of great power politics, that policy was foreordained to provoke a violent reaction from Russia.

I’ve found myself on the whole respecting Mearsheimer’s willingness to stand tall and take heat for a contrarian position - particularly in this adversarial interview with The New Yorker. At the time I was in Ukraine, in April/May, I sincerely felt that Ukraine had all right on its side, that the United States was participating exactly as it should in the conflict both as an ally and as a participant of the international community, and that somebody like Mearsheimer was more or less a traitor. By June, I started to wonder if I had been really naive. The United States’ involvement in the Ukraine war had turned out to be far more extensive than was commonly understood (active intelligence for strikes against Russian generals and Russian warships) and then there was a whole piece of the equation that still hasn’t been widely reported - the active involvement of United States special forces in reconstituting Ukraine’s military post-2014. Take all that together and I started to wonder if I had been fooled, along with the entirety of Western media - i.e. that Putin’s apparently overheated rhetoric was actually more or less accurate, that the United States has been treating Ukraine as an armed colony since 2014 if not 2004 somewhat in the way that the Soviet Union exploited Castro’s revolution, and that Putin’s invasion is at least within the realm of comprehensible statecraft.

In the spirit of open exchange, these ideas are worth talking about - it does feel as if the United States is wandering blithely, cheerfully into some sort of permanent war with Russia without really thinking through the consequences - but Mearsheimer’s talk makes it clear to me that Mearsheimer is not an honest broker for that perspective.

Most egregiously, Mearsheimer cherry-picks his quotes from Vladimir Putin’s notorious 2021 essay ‘On The Historical Unity of Russia and Ukraine.’ “You want to establish a state of your own? You are welcome,” writes Putin, addressing Ukraine. And as to how Russia should respond to Ukraine’s drive towards independence, Putin writes, “There is only one answer: with respect!” And yes, these are startling things for Putin to have written - and at odds with the one-dimensional way Putin is portrayed in Wetern media. But Mearsheimer perfectly ignores Putin’s dramatic slight-of-hand- in which, in the very next sentences, he claims that, in this particular case, Russia’s mystical, historical ties to Ukraine (Kiev as the mother city for all of Rus! the ringing call for unity by Oleg the Prophet!) obviate any trivial, latter-day considerations like the rights of nation states or Ukraine’s ability to make up its own mind. “But the fact is that the situation in Ukraine is completely different. Our spiritual unity has been attacked,” writes Putin. “Together we have always been and always will be many times stronger and more successful. For we are one people.”

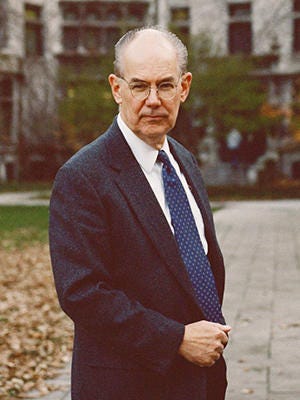

So that makes it pretty clear what’s going on - it really isn’t possible to conscientiously read ‘On the Historical Unity of Russia and Ukraine’ and to conclude that Putin’s purpose in writing it was actually to ‘respect’ Ukraine’s territorial integrity; and for Mearsheimer to read it in that way means either that Mearsheimer is hopelessly naive or that he’s cynically funneling all available evidence into some pre-packaged narrative about the essential goodness and rationality of Vladimir Putin. And, strangely enough, it seems actually that John Mearsheimer, Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago, ‘most influential realist of his generation,’ is in fact hopelessly naive. Mearsheimer claims that “in all of Putin’s public statements during the months leading up to the war, there is not a scintilla of evidence that he was contemplating conquering Ukraine and making it part of Russia” - not even, you know, troops massing on the border. And, incredibly enough, Putin’s steadfast commitment to the territorial integrity of Ukraine continued right up until February 24th - when, in his announcement of ‘Special Operation Z,’ he declared, “It is not our plan to occupy Ukrainian territory.” There is, Mearsheimer concedes, the very slight possibility that Putin might have been lying about his motives during the build-up to the war, but, as luck would have it, Mearsheimer has written the book on lying in international politics (sort of like Neil Gorsuch wrote the book on legal precedent) and if Putin had been lying Mearsheimer would have been the first to know. “And it is clear to me that Putin was not lying,” Mearsheimer writes. QED.

For me, Mearsheimer’s talk more than dismisses him as a serious intellectual on the Ukraine war, but his woozy thinking is symptomatic of a larger issue. There’s a dangerous tendency on the Left to see all international action as flowing solely from the United States. It shows up, for instance, in Andrew Bacevich’s piece for Tom Dispatch or in The Nation’s craven coverage of the war, which amounts to begging Ukraine to surrender. Somebody like Mearsheimer, with his realpolitik credentials, is an invaluable ally for that school of thought - he creates a strangely cozy sort of illusion, that the United States is the only real actor on the world stage, that American imperialism is, as usual, to blame for everything, and with the implication that Putin, by contrast, is fundamentally rational and reactive, attempting just like everybody else to keep from being ground under the wheels of American imperialism. That sounds like tough-talk cynicism, but the reality is actually more bracing than that. It is a multi-polar world, in which evil can emanate from many different directions, and it’s full of difficult decisions. America’s perfidies don’t excuse us from the moral judgment of figuring out what to do when a foreign power is the aggressor. And, yes, there is a case to be made that the United States acted foolishly in extending NATO eastward during the ‘90s, in quasi-opening the path to Ukrainian membership in NATO, in intervening in Ukraine’s revolutions in 2004 and 2014, but, look, the United States is not the one raining down bombs on Kyiv or massacring bicyclists in Bucha. There is such a thing as being too clever - and a valid critique of U.S. imperial policy is an easy way to be distracted from the horrors of Putin’s invasion.

Hi Isabel,

Thank you for the comment. I'm not crazy about Gawker - I don't think their response cuts very deep - and I have some difficulties with their premise. The claim is that what happens with Diego is a sensationalistic 'new angle on an old story' (i.e. bullying) and that focusing on him privileges male over female suffering. First of all, pain is pain, different people struggle in their own distinct ways. And, secondly, I don't think this is an old story. There are new tools (online posts) that have been rapidly weaponized. It's the job of journalists to tell those stories as they unfold. As far as I can tell, Weil did a great job reporting this piece - spoke to everybody, etc.

- Castalia

I feel a lot worse about Jane Roe than I do about "Diego"