Dear Friends,

I’m catching up on movies. These are more discussions than traditional reviews. Hopefully, there is something of value in these if you haven’t the film but they’re written with the assumption that you have. At the partner site

, interviews Lore Segal. I have a piece up at on political homelessness.Best,

Sam

AMERICAN FICTION

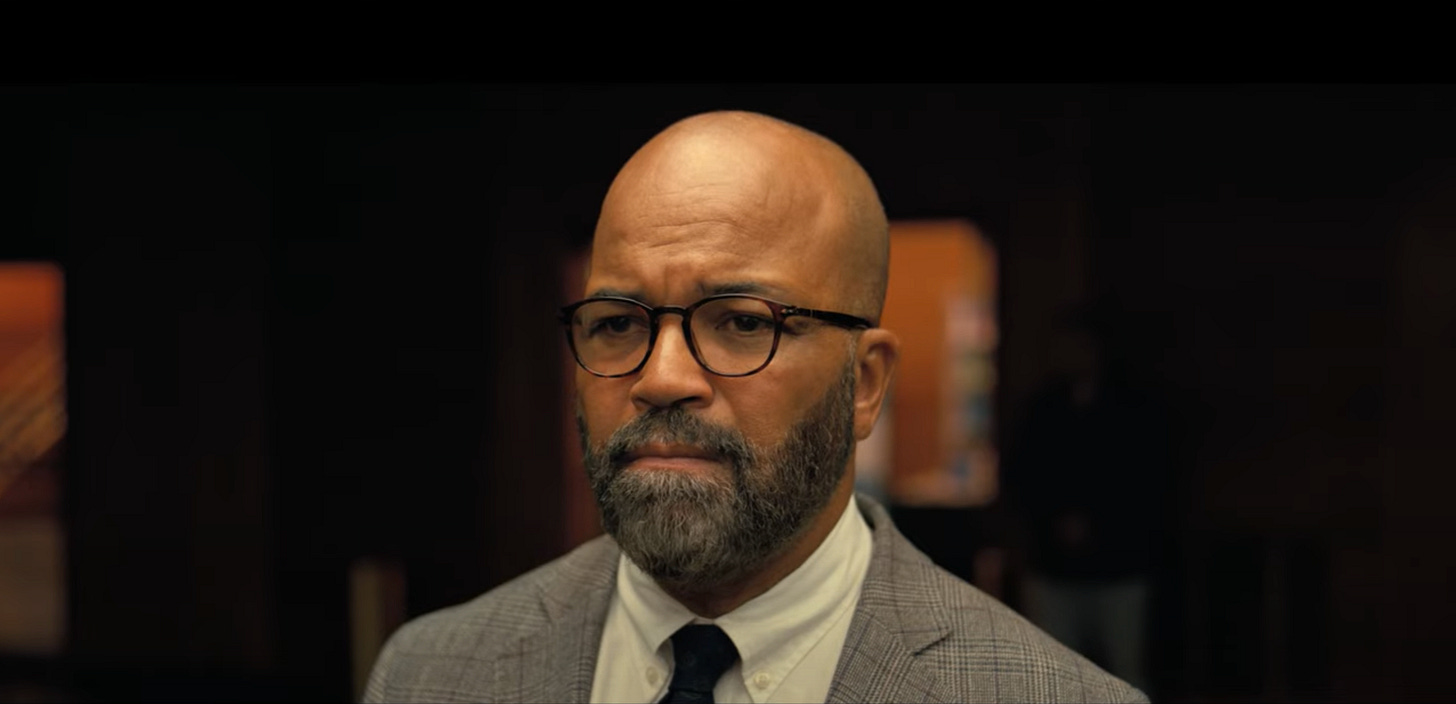

dir. Cord Jefferson, based on Erasure by Percival Everett, with Jeffrey Wright as Monk and Sterling K. Brown as Cliff

One of the best movies I’ve seen in a long time.

The feeling here is of waking up from a dream — and there have been a few works of art that have been instrumental in it. Jeremy Harris’ Slave Play poked fun at the pieties of wokeism.

‘s This Is Pleasure and Todd Field’s Tár took seriously the stories of the canceled and of the moral complexities of their experiences. American Fiction is a chance to shake ourselves out of the mindset completely, realizing how much bad faith, self-delusion, and plain absurdity went into the Woke Period.Percival Everett is the perfect figure to carry out that society-wide cure. He is smart, subtle, and — much to the consternation of the mainstream press — has, throughout his career, resisted easy classification. I was very impressed with Dr. No. I sort of didn’t realize how funny and idiosyncratic he really was until I saw American Fiction.

The point with American Fiction is that wokeness — particularly as it manifests in art — is a great reducer of human complexity and that that reduction to racial categories, and stereotypes of racial categories, brings no benefit to black people, even notwithstanding some tactical gains. In a sense, the main plot of the movie is Monk’s stalking of Sintara — his attendance at her reading, his agreement to participate in a panel of judges that includes her, his badgering her with questions — and what he’s trying to figure out is if Sintara is broken by her selling-out, if there can possibly be good faith behind a book like We’s Lives in Da Ghetto.

“You’re not fed up with it?” he says. “[Portrayals of] black people in poverty, black people as slaves, black people being murdered by police….I’m not saying these things aren’t real, but we’re also more than this.”

Sintara holds her own in the conversation — she thinks Monk is elitist, that Monk is fixated on some vision of upward mobility — but the point goes to Monk. “I think I see the unrealized potential of black people in this country,” he says — and what that means, really, is a completely different aesthetic and a society-wide ability to grapple with nuance: an understanding that a black man can write a book about Aeschylus’ The Persians and be no less ‘black’ as a result (“They want a black book,” Monk’s agent calls to complain, to which Monk responds, “They have one, I’m black and that’s my book”); a willingness for movies to say what they have to say without neat resolutions (“I like the ambiguity,” says Monk to a Hollywood director, who, of course, vastly prefers a shootout scene); a greater granular attention to the actual messiness of people’s actual lives. “I’m ok with giving the market what it wants,” says Sintara in her slot for a rebuttal, and that really is a damning critique not only of the Woke Era but of many American aesthetics that have come before it — the market wins; the stereotypes and the tidy stories prevail; and a complex, idiosyncratic writer like Everett ends up being denied a place in the culture.

There’s another, even more cutting, critique of the aesthetics of Wokeism. It’s in Monk’s line to his agent, “White people think they want the truth, but they don’t. They just want to feel absolved.” With that, the aesthetics of the last decade are seen for what they are — not a dealing with black people or black lives but a Great Awokening, evangelical-ish drama of forgiveness and redemption. Meanwhile, a different religious sensibility emerges through American Fiction — a tougher, more grounded and grown-up sort of religion — and it’s part of the strength of the film that Monk has to work hard to really take it into himself.

In American Fiction, Monk’s sister Lisa is the first adherent of this religion. The elegy she writes for herself, and which Monk reads, is a masterpiece of groundedness and clear-eyed maturity. She writes:

If you are reading this, it's because I, Lisa Madrigal Ellison, have died. Obviously this is not ideal, but I guess it had to happen at some point…Irrespective of how I went, I ask that those closest to me not mourn all that much. I lived a life that made me proud. I was loved, and I loved in return. I found work that aroused my passions. I believe I gave more than I took, and I did my damndest to help people in need.

I’m skipping over the funny bits in that elegy, but these lines convey the real point: that it’s possible to live a good, proud life without airy narratives of redemption or social revolution, just by really grounding oneself, accepting one’s singularity and doing the best that one can. Cliff, Monk’s wild brother — who seems to have picked up a good deal of Lisa’s edifying influence while Monk was off with his books — takes that religion as deeply into himself as Lisa does. “People want to love you,” he tells Monk at a difficult moment in their relationship. “You should let them love all of you.”

If Cliff is unhinged where Lisa is responsible, he also has the ability to harmonize all the different sides of himself — even as Monk, so smart, so intellectual, boxes himself in with his secrets and compartments. Where Monk gets to by the film’s end isn’t quite the level of self-possession of Lisa or Cliff — he accedes to the Hollywood director’s idea for the smoke-‘em-up end of the film; he finds himself sitting on a studio lot and locking eyes with a black actor in a slave costume, both of them struck by the distance it will take to really be free; his compartmentalization and secret-keeping have cost him a good relationship with Coraline — but the sense is that he’s on the right track. He’s put one over on the market, he’s become a better son and brother, and, in some sense most importantly, he’s become more sure of his aesthetic: he knows that the absolution tropes (Sintara’s path) are just a marketing gimmick and that real art and real freedom come from dealing honestly and unflinchingly with the complexities of his own life.

THE HOLDOVERS

dir. Alexander Payne, written by David Hemingson, with Paul Giamatti as Paul and Dominic Sessa as Angus

…And speaking of all of which, there’s The Holdovers, which in its well-meaning but bumbling way epitomizes kitsch in our era.

Essentially, The Holdovers is two crappy, played-out genres combined together. There’s the prep school elegy — with the long shadow of A Separate Peace and Dead Poets Society, not to mention The Catcher in the Rye, the tale of the prep school misfit looking to escape the confines of the dress code and stultifying patriarchy — and then there’s the Woke Manifesto, the revelation through a skeptical, sort of strategically-placed black character, of just how incurably racist and depraved American institutions are.

And, in The Holdovers, both genres are distilled down to their milquetoast essence. The prep school hell becomes the can’t-miss-it-bonding-experience of the Holdenesque student held over for a full winter vacation, forced to form a human connection with his unlikeable-yet-as-is-turns-out-surprisingly-sympathetic teacher tormentor. And, as for the Woke Revolution, we get not only the wise black cook but the wise black janitor and we get the injustice of the system with in-your-face clarity: the cook’s son, the only black student at Barton Academy, is also the only one to die in Vietnam. It’s worth comparing Mary in The Holdovers with Lorraine in American Fiction as a kind of object lesson in treacle and filmic sophistication: Lorraine, with only a fraction of Mary’s screen time, is far more arresting, with her romantic subplot and the complex loyalties of her service with a black family; while Mary just kind of smokes and drinks and dispenses nuggets of rough wisdom and, in the reductivized cosmology of The Holdovers, is understood to be not only superior to everybody else in the movie, infinitely suffering and infinitely competent, but (it can be quietly observed by how much better they are their paprika dosage) even the black line cooks working for her in her kitchen are superior to the whites.

I found The Holdovers pretty tough to get through, but there is something interesting in it that comes across by the end. And that’s a sense of really heightened unpleasantness — of two men, Paul and Angus, being in such excruciatingly close proximity to each other that they can’t help but notice a certain shared resemblance. In The Holdovers, awkwardness and unpleasantness are sort of permanent afflictions — Angus will always be disliked; Paul will always be strange and unpleasant. There’s no chance of somehow overcoming their character deficiencies — and they can never quite bring themselves, even in the thick of bonding, to enjoy the company of the other one. In The Holdovers, it is a long, long way to their somewhat stiff handshake at the movie’s end.

“Keep your head up,” says Paul.

“I was going to tell you the same thing,” says Angus.

And in the context of this time and this world and the insuperable awkwardness of males with other males, that’s as close as they can get to the long-awaited bonding — a shared, limited acknowledgment of each other’s humanity and each other’s struggles.

The strongest moment in The Holdovers is a line that Paul delivers after he meets a college classmate of his and omits the painful story of how he came to be expelled from Harvard. “Why did you lie to that guy?” innocent Angus asks him. To which Paul says, “He’s not entitled to that story, I am.”

It’s a good line, departing from the usual American movie formula of hugging and crying. Openness is the solution in most films — certainly, in films that are as genre-bound as The Holdovers and in films dealing with the ‘60s — and Paul’s line seems to come from a tougher and more sophisticated movie, with a recognition that most adults live their lives actually in very closed ways, that being closed can be an important means (especially for people who have gone through real pain) of retaining pride.

But if lines like that one point towards something strong and mature, Hemingson’s script has a way of collapsing into broad brushstrokes. Do we really believe that shy Paul, at a bar in Boston, would lecture a working-class Santa on the Classical Greek origins of the Christmas story? Does Paul really mutter the word ‘philistines’ to himself and does he, as an intelligent adult, actually recite the prep school motto with no trace of irony?

The writing is a somewhat obvious target in The Holdovers, but this is also the place, I believe, to say for the record that Paul Giamatti is not good at acting. I don’t have some sophisticated critique here. It’s just that his instincts aren’t what they should be for an actor who’s gotten the kinds of accolades he has, and if he’s able to compensate for that with an intelligent, sympathetic approach to his roles, he also has a tendency towards scene-chewing. Comparing Giamatti with Jeffrey Wright (both of whom were nominated for an Oscar today) is a good exercise also in comparing Woke-ish art like The Holdovers with a freer, edgier, uninhibited work like American Fiction. There is something very safe about Giamatti’s performance in The Holdovers. He knows that the audience will be on his side — the loser with the heart of the gold — and the beats of his character seem determined from the first time we see Paul and his unfortunate sweater. Meanwhile, in American Fiction, Wright is constantly taking risks: he’s moving in and out of black stereotypes, he’s flirting with a very unattractive cynicism. Very often in American Fiction, we are not at all sure if we are rooting for Monk — he can be pompous, selfish, impossible — but Wright is invested in getting at all the uncomfortable corners of his character (and Wright is also just an unbelievably talented actor, who, in the way that some athletes can hang in the air longer than others, seems to have an ability to suspend a beat in a way that no one else can) and the result is a movie that’s immaculately crafted and, also, really risky — a movie that powers its way out of the overwhelming kitsch of our era.

I'd thought American Fiction looked interesting, but when I saw it on Barack's list of his favorites of 2023 I'd concluded it was probably upper middlebrow pandering at its worst! But your review has persuaded me to check if it might still be playing somewhere nearby.

I loved this movie. It has cult classic written all over it