I was in a book club once, not at all sure I wanted to be there, and another member of it, a perfectly pleasant, well-educated person, said, after a desultory discussion, “I think I’m only going to read memoirs from now on, not novels,” and that decided me – no more book clubs.

The problem was that I completely understood her point of view. The novels we were reading – book club books – really were very gray, derivative, second-hand. Very often – they tended to be edifying historical novels – they seemed like some kind of a gloss imposed on a historical event, bonus material giving the possible inner monologue of an historical figure or capturing the flavor of some lost era. Compared to that, it really was much more fascinating to read anything from the era in question, a diary entry, a letter, whatever it is, there was something inescapably raw, authentic, about it. I felt this very acutely since I was working in documentary film and spending the evenings writing fiction, and I treated documentaries as a day job, hack work, it was pretty easy at the end of the day to convince somebody to be in a movie, stick a camera in their face, and have that be pretty arresting almost no matter what they were doing – there was something thrilling about capturing reality in this way – and that was easily marketable, while fiction, which took real sweat and energy and these great unexpected leaps of imagination, was interesting to basically nobody. It was the sinking feeling I had every time I opened The New Yorker, and even though I was avowedly on the side of fiction, found myself skimming or skipping the story, heading for the profiles and the talk of the town, hunting for some info on the world around me, or some gossipy knowledge about famous people.

Publishing, as everybody knows, is mostly an appendage of the celebrity industrial complex – that’s what sells, dirt of some sort on already famous people. But there’s another genre that seems to work, which is memoir – somebody can be completely unknown but so long as they had sufficient trauma in their youth, so long as they overcame adversity, there’s a place for that in the market. David Sedaris, Augusten Burroughs, J.D. Vance, these are the writers with their hooks in the culture. The pattern is so familiar that the better of the memoirists are embarrassed by it. “I find the existence of the book you’re holding somewhat absurd,” writes Vance in the introduction to Hillbilly Elegy. “It says right there on the cover that it’s a memoir but I’m 31 years old and I’ll be the first to admit that I’ve accomplished nothing great in my life.” At which point Vance then justifies why he’s writing it: because he grew up poor, in conditions that are emblematic of greater social ills (i.e. the demise of the American Dream, the stagnation of Appalachia), because he had a difficult childhood, because one of his parents suffered from addiction, because he nearly succumbed to addiction himself, because he “nearly gave in to the deep anger and resentment harbored by everyone around me,” and because he got through it, graduated from Yale Law School, managed to “achieve something quite ordinary,” marriage, home ownership, a job, a nice life. That’s the trajectory of the memoir – the lowest of the low, toxic childhoods, abusive relationships, the pits of addiction, and then, usually somewhere offstage, the getting-it-together, education and professional success, a sense of perspective, and, although it’s never said explicitly, the triumphant ending of the memoir being sold and favorably reviewed by The New York Times and the now-uplifted author living happily ever after on book tours and royalties. And all of it an object lesson for the person reading it, who, as likely as not, hasn’t suffered trauma to the same extent, who is merely stuck in their life, but can relate and be inspired – if this person can do it, coming from where they came from, then I can do it too.

This is the trend, and it seems irreversible, a fictional story might speak well or badly of the creator; a true story, though, is a story that matters. Note the incredibly satisfying moment at the end of a movie, when ‘based on a true story’ is written on the screen, like a clincher – and everybody in the audience has this pleasurable shiver, transposing what they’ve just seen into the ‘real world,’ imagining all the traumas, the suffering they’ve just witnessed, happening to actual people. Since I’m a partisan of fiction, though – since I really loathe myself every time I flip past the short story in The New Yorker – I find there to be something horrific about all of this.

As usual, the most obvious answer is to blame everything on the Christians. The structure of the memoir is a confession; the arc of it is the same as one of the lives of the saints. The narrative arc at least since Augustine is to emphasize the depth of the sin, the hopelessness of the case, the better to set it off against the subsequent grace, the eventual beatification, with the sole difference that in the modern memoir the aim isn’t the saintly, spotless life but adjustment, the twelve steps, the job, the love-of-one’s-life, the cogency to write a memoir and to have it be funny and touching – the fact of the memoir like a testimonial that there is a way forward, that redemption is possible. The problem is that there’s an inherent competition, as in some prayer meeting, for the story of the sin, of the bottoming-out, to be as terrible, as traumatic, as possible – addiction, abuse, crime, as much as possible, as awful as possible. “I have no happy memories from my childhood,” begins Édouard Louis’ The End of Eddy, encouragingly. And, as in the JT LeRoy phenomenon, there’s a vast disappointment when it’s revealed that the trauma may not have actually happened as it’s depicted in the book, that the “permeable membrane between author and subject,” as one reviewer put it, was actually much wider than everybody initially assumed – and, as in that case, a certain widespread relief when it was reported that Laura Albert, the true author, may not actually be a teenage trans runaway prostitute but had had her own traumas, that the book was initially written not as some cynical, imaginative novel but as a confession delivered to a therapist.

Confession is the important word. We’re a bit shy about it because we’re supposed to be in a post-Christian, post-religious society, but it’s the same set of techniques: the therapist replaces the priest, every cop show ends with the criminal’s confession, the memoir gives the inner truth, what religious people would call the imprint of the soul, and literary fiction tries to get in the game with its compromise ‘autofiction’ (which, by the way, is a fancy word for memoir with some stuff made up).

Somewhere – in our heart of hearts (a very evocative phrase) – we know that this isn’t as it should be, that the novel is high-brow and the memoir, like the lives of the saints, middle-brow at best; we know that it’s more impressive, more interesting, to make up whole fictional universes as opposed to just repeating what happened to you as a kid, but we can’t stop ourselves, we’re addicted. I remember something mischievous, guilty, in the tone of the book club member when she admitted that she didn’t want to read novels anymore.

***

I’ve been just generally annoyed about all of this for a while and then I read a piece by James Hillman, ‘The Captive Heart,’ that helped to frame it. The issue, says Hillman, has to do with a chain of metaphors connected to the heart, which we have managed to see in the most narrow, constrictive way possible. Our heart – what Hillman calls ‘the heart of Augustine’ – is a personal heart, a feeling heart, that is intimately connected with our life experience; and is capable of taking in nothing else. If we are moved by something, it is ultimately because it reminds us of something that has happened to us. And therapy – which is the main target of Hillman’s piece – is a constant reduction back towards the ‘heart,’ feelings, personal experience, whereas anything external is taken to be a projection and anything imaginative a flight from the deeper emotional truth. Authority in this framework falls to people who feel the most, which, ipso facto, means the people who have suffered the most. The veteran, the victim, the survivor are the ones who have ‘been through so much,’ they’re the ones we trust to have the most feeling, to have the experiences most worthy of being conveyed, they’re of course the ones who write memoirs. Politicians are constantly giving us their origin stories – John Boehner the bartender’s son, Marco Rubio whose mother was a hotel maid – all of them having overcome their backstory to attain power and prestige but also able to perform a conjurer’s trick of taking on everybody’s personal suffering: they feel your pain, their heart goes out to you, they speak with a heavy heart. The rhetoric of intersectionality of course takes these tendencies and brings them to an extreme in a precisely-tabulated matrix of suffering, victimhood implying greater depth of feeling which implies greater moral authority.

It is no surprise that, in a society dominated by the Augustinian heart, artists are pushed constantly towards the personal. ‘Write what you know,’ is the opening advice of all writing teachers. ‘Everyone has one book in them’ is a favorite aphorism – the implication is that everybody has a story, tap into a certain emotional layer and you can tell that story but only that story. The ‘novels’ that are marketed as such – Kate Zambreno’s Drifts, Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts, Ben Lerner’s Leaving The Atocha Station, Tao Lin’s Taipei, I’m just thinking of what I happen to have recently come across – are extremely narrow, vanishingly personal. If nothing is happening in the world, if everybody is constricted into their tranquilizers and their Internet personae, well then, that’s reality, that’s your story, you have no choice except to write about that. And whenever someone tells their story, there’s a set of phrases to bestow on them, as readily available as those which a revival tent can pour onto a new convert: ‘brave,’ ‘honest,’ ‘unflinching,’ ‘heartfelt,’ all of them, ultimately, forms of moral approbation.

What’s completely lost in this exchange is imagination. Here’s how Hillman puts it:

“Now we see what happens to the imagination in a heart of personal feeling. By personalizing the heart and locating there the word of God, the imagination is driven into exile. Its place is usurped by dogma, by images already revealed. Imagination is driven into the lower exile of sexual fantasy, the upper exile of metaphysical conception, or the outer exile of objective data, none of which reside in the heart and all of which therefore seem heartless, mere instinct, sheer speculation, brute fact. When imagination is driven out, there remains only subjectivity - the heart of Augustine.”

Think of all the faculties that human beings can possess that are completely missing in the culture, or were until very recently: mythmaking, storytelling, visualization, projection, trance. I remember how startled I was the first time I did a visualization exercise or trance or deep breathing or meditation for that matter, these were very simple state shifts, they really only took a certain relaxation, but they were shifts, suddenly I was unfamiliar to myself, my story, my identity couldn’t possibly have mattered less. In the case of a few trance exercises it also became clear that a group consciousness was at work, that the various participants in the exercise were sharing fragments of a collective dream, sometimes everybody coalescing on a particular image, a pain in the left shoulder that afflicted the entire group, sometimes people’s memories getting dispersed and passed around like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. And same went when I had my first breakthrough writing, instead of circling around the drain of my story, which had very little trauma in it and wasn’t interesting, least of all to me, I started writing, first in the voice of a 19th century New England woman, then a Somali pirate in Addis Ababa, then a Romanian gymnast, then a right-wing talk show host. It didn’t really matter to me whether it was good or not, whether it was authentic, what surprised me was that it was possible at all, with no particular volition, just following a few haphazard inner voices, I was suddenly in the consciousness of all these people from all over the world – which was, if nothing else, more fun than following around the marble of my own thoughts and own life.

In Hillman’s terms, this is all part of a different and much older conception of the heart. He calls it the ‘coeur de lion,’ heart of the lion, which is contingent on the fact that it believes. For me, the burst of imagination in writing was linked to a sudden confidence – someone giving a whisper of encouragement, then a not caring of what was good or not good, what was me or not me. And same for the trances and the visualizations, there may very well have been an element of collective delusion, of our all wanting to see certain things and then seeing them, but so what – they were things that everybody in the group felt, that we truly felt at the time, and in the rubric of the coeur de lion, our believing made it so, there was nothing really to demarcate where the experience stopped and so-called reality started.

Hillman’s writing builds off the Sufi scholar Henry Corbin, who describes the heart as ‘himma,’ an idea of the heart that is almost perfectly opposite to the Augustinian. There, the heart is not the seat of feeling but of sight. It is intimately tied to the imagination. Here are – from Hillman – a few quotes on ‘himma’ to give an idea of it:

The place of himma, throbbing out its imaginative forms.

The passionate spirit of himma that moves through the heart.

Himma demands that images always be experienced as sensuous independent bodies.

Himma presents the images of the heart as essentially, though intimately, real; yet the reality of its persons is independent of my person.

Himma creates as ‘real’ the figures of the imagination, those beings with whom we sleep and walk and talk, the angels and daimones who, as Corbin says, are outside the imagining faculty itself. Himma is that mode by which the images, which we believe we make up, are actually presented to us as not of our making, as genuinely created, as authentic creatures.

Think of the spirit world, think of the dreams in Homer, think of the clear images and felt truths one obtains from psychedelics, think of the quality of the Greek myths, the sense of a completely intact imaginal world distinct from autobiography. It’s not so easy to describe. As Hillman writes, “We are bereft in our culture of an adequate psychology and philosophy of the heart, and therefore also of the imagination.” Think of the fantastical confidence one encounters in people who are not born to a Western materialist mindset – a more permeable boundary between self and surrounding, a sense that strong, devoted belief can shift reality, a lack of interest in ‘fact.’

A good way to think about this is to compare Shakespeare’s plays, and how they probably actually were written, with 19th century interpretations. In the late 19th century, when the Baconian and Oxfordian hypotheses came into play, the assumption suddenly was that the author of the plays must have been a courtier, a soldier, a lawyer, must have traveled the world, must have had some dazzling array of experience in order to have had lived all the events detailed in the plays. “Experience is an author’s most valuable asset,” wrote Mark Twain in his essay attempting to disprove Shakespeare’s authorship. “Experience is the thing that puts the muscle and the breath and the warm blood into the thing he writes.” Twain was of course a great writer and he was thinking of himself – he’d lived just about everything he wrote and couldn’t imagine it any other way. By his token, Shakespeare, who was believed to have been a butcher’s son, could have written only Titus Andronicus, which seems to contain a knowledge of butchering – and the search had to be conducted for some true Renaissance man, like the Earl of Oxford, who had been at court and in sieges, had some higher percentage of the experiences of the plays. That was a late 19th century conception of how creativity worked, subject to the prejudices of a mechanical, unimaginative age – there was a similar refusal to believe, when The Red Badge of Courage was published, that its author hadn’t actually served in the Civil War. That whole discourse would have been completely alien in Shakespeare’s time, and it’s telling that his authorship of the plays wasn’t questioned for 250 years when, suddenly, it was assailed on all sides – from an Elizabethan mindset, there was no more reason to link Shakespeare to the material of the plays than to assume that Sidney must have been to Arcadia or Spenser met the Faerie Queen.

Shakespeare had lots of himma. It seems completely clear, actually, how he wrote the plays – he read the source material, all these lively but uncrafted tales and chronicles, they sparked something in his imagination, and he invented whole fictional universes out of them. Simple as that – what Keats described as negative capability.

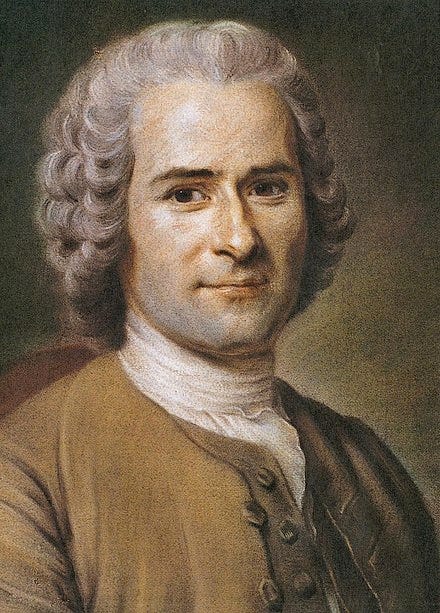

Since that time, the Western heart, the Western imagination has shut down. Hillman traces the reduction of himma, the coeur de lion, to the mechanical heart of Harvey and then, with Protestantism and the rival of Augustine, to the personal heart, the heart of autobiography. Rousseau becomes the successor to Augustine and his Confessions, masterpiece of the genre that it might be, founder of the modern memoir, has a curiously anemic feel. You wouldn’t know, from reading it, that there was anything special about the author, wouldn’t connect its bourgeois protagonist with his endless bad habits and muddled career to the revolutionary thinker who founded modern anthropology, sociology, pedagogy, Romanticism, and all left-wing political thought. Because it is a record of sin. “Let the trumpet of judgment sound when it will, I will present this book before the Supreme Judge,” Rousseau writes in the opening. “Assemble about me the numberless host of my fellow men, let them hear my confessions, let them groan at my unworthiness, let them blush at my wretchedness.” The framework is ostensibly different, Rousseau is a secularist, a free-thinker, but he shares Augustine’s notion of the self: sinful, polluted, and what matters is not the work, not the expanse of imagination, but the record of the life, which is to be weighted in the moral balance. Rousseau likely meant for The Confessions to be the entire record of himself – “This is the only portrait of a man, in all its truth, that exists and will probably ever exist” – but then he seems to have sensed that something was missing. Reveries of a Solitary Walker is a kind of coda to The Confessions, and, from my perspective, a much better, less dogmatic book. It frees the self from the restrictions of autobiography, it places the self in a dreamscape, it creates the free-floating persona of Bergson and Proust and of Whitman – “I loafe and invite my soul.”

It is very hard to escape the personal heart, the autobiographical self. The culture militates for it. Everything is about the confrontation with the self: ‘face yourself,’ ‘deal with yourself,’ ‘own yourself.’ As Hillman puts it, “Confession supports one of our most cherished Western dogmas: the idea of a unified experiencing subject vis-a-vis a world that is multiple, disunited, chaotic.” Even our actors are always playing themselves – dealing with their emotional truth; a long way from the coeur de lion in the old acting tradition that finally ended in the late 19th century. I wouldn’t expect it to change any time soon, any more than I would expect a return to Sarah Bernhardt’s acting – we are obsessed with authenticity, honesty, we are still exploring realism. And identity politics – the fear of ‘appropriation’ – of course puts the nail into the coffin of any kind of imaginal play. Stick to your lane, tell your story, is the dogma we’ll be dealing with probably for a long time – the more misery, the more suffering, the more worthy the story. My point is just that that’s not the only way to be. Whitman, who was always right about everything, wrote “I am large, I contain multitudes.” This is himma – not the narrow, Protestant, Augustinian self, dragged before the host on Judgment Day, assessed according to a deed book, some ledger of sin. A self that is capacious and wild, the sum of everything felt and imagined – a kosmos.

So many ideas, I almost don't even know where to start. I think I've been getting a little tired of complaints about autofiction and memoir, so I'm very glad you moved past that to something deeper. I hadn't heard of Hillman, he seems very interesting, but I really like the idea that other cultures have a different conception of the heart, which means basically a different conception of self and of truth. Lots to think about!

Thanks for writing these thoughtful essays. Looking forward to reading more. Would be interested in your pov on Orwell, who wrote both memoirs and novels basically covering the same topics. And in this day, if you were choosing are "Down and Out in Paris & London" or "The Road to Wigan Pier" better for a book group -- or a high school English class -- than "Animal Farm" and "1984"?