Dear Friends,

I’m sharing a ‘Manifesto.’ At the partner site

, co-founder features the last-ever interview with the wonderfully-mustachioed LeRoy Neiman and reflects on Disney.Best,

Sam

AGAINST BRANDING (AND SARAH FAY)

There was a Substack post recently by Sarah Fay that got under my skin. “Write less please,” Fay advised. “There’s a time and place” for long-form writing, she continued, and concluded, based on a host of viewership data, that Substack wasn’t it.

I found myself feeling personally insulted by that, since — as you may have noticed —posts on this Substack routinely drift north of ten or even twenty minutes and are sometimes too long to be fully ‘delivered by email.’ I’ve gone through a certain amount of soul-searching about this and have decided, basically, that I didn’t care. Anybody is free to stop reading or to unsubscribe. I wanted to do justice — as best as I could — to whatever I was writing about, and that often involved taking in nuance and counter-arguments at the expense (almost certainly) of audience numbers.

But Fay is obviously intelligent — and with the sort of intelligence that I am, secretly, most afraid of: it’s the intelligence of somebody who is completely confident that they know how the world works and, with the benevolence of a friendly aunt or uncle, is willing to tell you how to optimize yourself to survive in it.

My annoyance with (and secret terror of) Fay extended beyond a question of word counts. For her, it was completely self-evident what the purpose of a Substack (and probably of writing in general) was. It was to grow. Build a following, make money, build a brand.

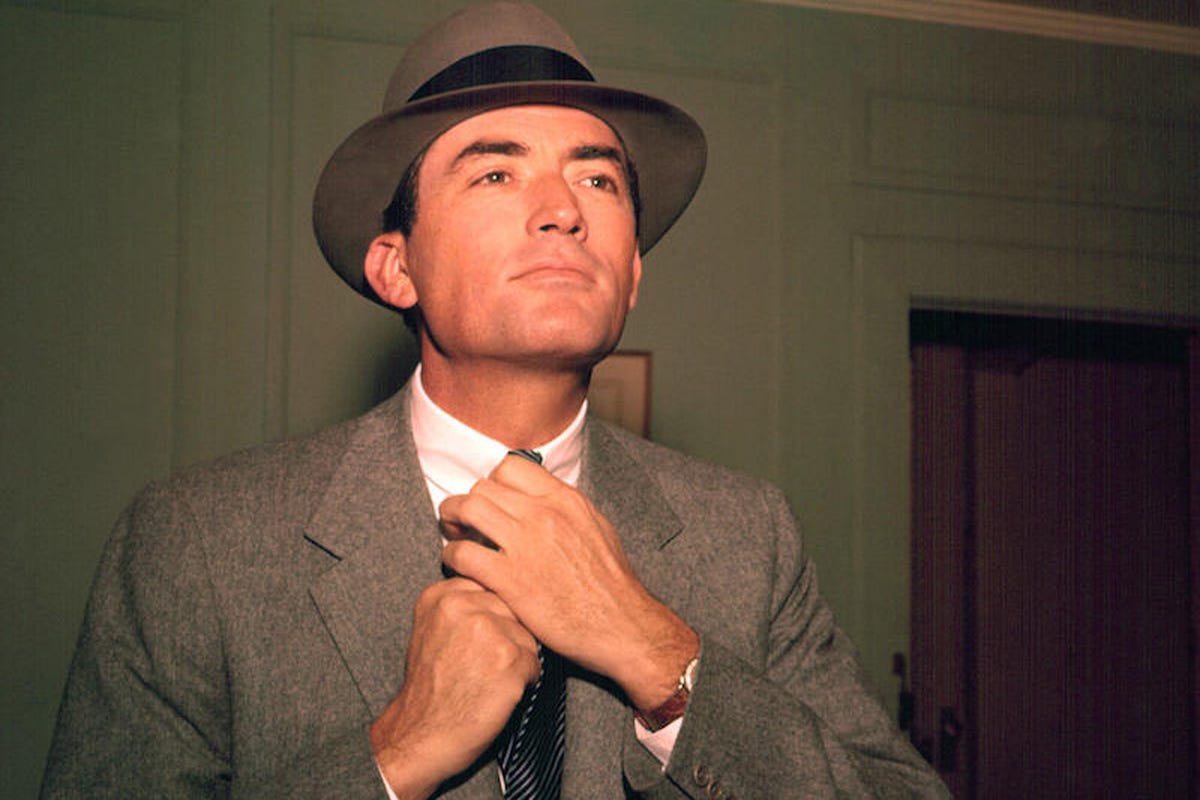

And here we get to the cursèd word and the real point of this post. The history of the idea of ‘branding’ is probably the real story of the individual in our time. The story would run something like this. The individual was conceived of, circa say 1950, as a cog in the great social machine. It was understood that the individual could be called upon to serve and to sacrifice themselves for their country (i.e. for the greater social good), and it was almost axiomatic that there was no higher way to live. Socialism, famously, took this concept to its extreme, but, within the capitalist West, various archetypal figures (‘the organization man,’ ‘the man in the gray flannel suit,’ the industrious housewife, etc) imagined themselves, with varying degrees of preposterousness, as being an integral part of a great social whole. The ‘60s represented a great irruption of centrifugal energy, with individuals of all walks of life finding themselves no longer believing in the nation-state or even in ‘society’ as a whole and, through psychedelics, sexual liberation, free-thinking, conscientious objection, etc, looking to institute a completely different notion of the self, of the individual as a self-sufficient, sacrosanct entity owing no particular allegiance to society. (All of this is an almost perfect recapitulation of the philosophy of Rousseau — these debates have been going on for a long time — but let’s keep the discussion to our own era.)

In the next few decades a peculiar compromise took hold. Inexorably, as if of their own accord, all the institutions of civic life broke down, yielding, by the 1990s, the ‘bowling alone’ paradigm, as documented by Robert Putnam. That would seem to have resulted in a golden age for the individual, but the individual lacked modes of active expression as had appeared to have existed in the ‘60. Instead, the individual was just a consumer with the ability to, for instance, save their own shows, and the world seemed to have entered a peculiar phantasmagoric era, in which Agassi’s ‘image is everything’ dictum seemed to be hard to refute and something like reality TV was a remarkably literal fulfillment of Warhol’s prophecy of fifteen minutes of fame.

The internet arrived as a clear savior for the cause of the individual. With the internet, the individual could be summarily extracted from the one-way street of consumerism and could, at the small price of entering into a technological system, participate in a thrillingly new two-way discourse in which the possibilities of expression appeared to be limitless. But it didn’t work. The sheer numbers of people on the internet appeared to drown out any self-expressing individual, and new technologies emerged that both capped expression (the 250 character count) and that rewarded easily-digestible ideas that fit within approved frames of discourse (the like button). Navigating within the new dispensation, which had shifted rapidly from anarchic wonderland to market, meant mimicking the behavior of commodities, but where the man in the gray flannel suit dedicated himself body and soul to selling some or other kind of widget, the new ‘individualistic’ entrepreneur was a salesman who always and only sold themselves.

Substack launched right in the dominant period of the individual-as-internet-brand and my experience of reading work on this platform has pretty much been of a clash between two modes of thought. On the one hand, there are the smart people like Fay, who are careful about throwing up paywalls, teasing their work, generating familiar, digestible content (advice for writers, in contrast to actual writing, seems to be a thriving genre), and, above all, ensuring that every post is on a topic similar to every other post — is ‘on brand’. And, on the other, there are the weirdos who explore the myriad corners of themselves, who write differently every time, and often write idiosyncratically, and for whom it takes some adjustment and energy to figure out what they’re saying.

As far as I can tell, Substack is about as idealistic a tech company as there is. The site really developed as a corrective to the restrictions on expression inherent in the Web 2.0 and as a platform for writing — and the Substack OG seemed to have been very adamant in avoiding promos and the totebag-and-upvote style of Patreon or Medium. But Substack is subject to market pressures, and to the spirit of the time like everybody else, and a recent mailbag of ‘Substack Reads’ strikes me as concerning. The spotlighted Reads were 1.travel tips for Italy, 2.‘meaning and stories behind the data in the NBA’s season schedule release,’ and 3.design tips for a ‘Parisian-style space on a budget,’ all perfectly professionalized, wholesome, well-branded Substacks, but none of them exactly what I (or I think the Substack founders) had initially had in mind.

If Substack, in different respects, is bending to the conventional wisdom of modern social media platforms, somebody like Fay treats that wisdom as close to an iron law of how communication must be conducted in the digital age. Like it or not, you are a brand, runs that line of thought camouflaged as the-way-things-are. You must be short, crisp, probably cheerful, and utterly recognizable to your readers. Do that and you will have health, wealth, and a steady stream of likes. Don’t do that and your existence will be as sad as a floundering penny stock’s.

The only rejoinder to that is — in a tremulous voice — to say that that’s not at all what drives me, or anyone I admire, to write. Writing is meant to be exploration, which means surprising oneself, doubling back on oneself, going off-brand. As Whitman put it, “I contradict myself; I contain multitudes.” As the Patrick McGoohan character in The Prisoner put it, “I am not a number, I am a free man” — to which the response by his captor was, of course, uproarious laughter.

Underneath this discussion is a certain confusion about what an individual actually is. In Fay’s paradigm, the individual is a self-creating agent, proactive, content-generating, but embedded, ultimately, within the market. (Or, as Logan Roy put it, reflecting on a lifetime within capitalism: “I mean, what are people? They’re economic units. They have values and aims, but they operate in a market.”) I’m aware of my own gushing naïveté as I write this, but I really do believe that this is a misrepresentation, that an individual is something very different — and is much closer to a multiplicity, an internal archipelago of often-conflicting desires and beliefs, while the job of culture is, to the greatest extent possible, to give that vast inner world full and free expression. In terms of what I would most like Substack to be, easily-digestible four-minute advice columns for writers comes way at the bottom of the list. The ideal platform I would want to participate in would have something like the scabrous, somewhat-unhinged style of the critical writing of, say, D.H. Lawrence, Edgar Allan Poe, or Karl Kraus. (And it’s not that that sort of free associative, often-internally-inconsistent writing could be pulled off only by great writers like Lawrence, Poe, Kraus; they were great writers because they were willing to write in this way, way beyond the borders of good taste and right up against the domain of madness.) I have some sense that Substack is at a hinge moment. Some of the initial enthusiasm may have been waned. I don’t know what the pressure is to make good on that early VC valuation but I imagine that it’s considerable. And, in an era of digital branding, the temptation is overwhelming to shift towards a more ‘branded’ mentality throughout the platform. But Substack was created — at least I signed on to that — as an escape hatch from the Web 2.0 and as, most ambitiously, a kind of incubator in devising a new conception of the individual. That effort is very much a work-in-progress — the ‘brand’ narrative is still so overwhelming. In the meantime, the imperative is to keep Substack weird! Out of experiments like it will gradually emerge an individuality that is more confident, more comfortable with its own internal contradictions, less prone to viewing itself simply as a living, breathing widget.

Just a note that Sarah Fay wrote me a very classy message. I should say that I'm being a bit hyperbolic in this post and picking a fight more from a spirit of 'friendly rivalry' and provocativeness as opposed to being 'against' anything. I really have nothing against 'growing' subscribers or 'boosting' income - that's obviously important for everyone writing. But in this post I wanted to speak up for the 'weird' side of Substack - and, as @Sean Sakamoto notes, it seems somehow important at the moment to say that. May all boats rise together!

This would have been so smart if it had been shorter. You could have said all this in 300 words. :)