Becca Rothfeld has a mean-spirited piece out called ‘why i am skeptical that substack can or should replace legacy media.’ (The lower-case letters are because, as an expression of her disdain for the ‘wretched’ Substack platform, she can’t be bothered to use capitalization.) I’ve meditated and slept on it before replying to the piece — and I’m trying to subtract like 15-20% of my indignation because Becca is to some extent being provocative and willfully contrarian — but even with those preliminaries, I’m livid.

I should say that I like and respect Becca’s writing. I’ve read her book and many of her articles. She’s emerged as a premier critic of my generation. And this piece is well beneath her. First of all, she finds several ways to be blatantly disrespectful. The piece developed out of a Substack altercation with “some guy,” whom she doesn’t deign to give a name to. It’s not ‘some guy,’ Becca. You’re having an argument with Udith Dematagoda, who is a literature Ph.D and writes thoughtful, creative prose that you as a professional reviewer should be interested in reading. Then, the platform is ‘wretched.’ The people writing on it are ‘rogue losers with little screeds’ or ‘a sprinkling of weird contrarian freaks.’

Rothfeld says a few really dumb things that we’ll get back to later, but let’s take the high road at least for a little while and treat this as a ‘teachable moment’ — as Rothfeld says in one of her notes to Dematagoda. Rothfeld’s piece — which can be thought of as a kind of aggrieved establishmentarianism — is based in a category error, which is to confuse the formation with the vibration, or the name of the thing with what the thing is doing. To her, there is ‘reporting,’ best pronounced with flared nostrils and housed, certainly, in a sprawling newsroom, probably with reporters shouting into telephones and with Bernstein and Woodward off somewhere hot on the case. And there is Substack, which is “a glorified blogging platform lol,” and is basically defined as being lesser than institutional reportage. The fact that Rothfeld doesn’t actually do reporting — that she writes book reviews, which can ipso facto be done without any of the fact-checking or institutional structures that she so extolls — is one of many weak links in her argument.

But let’s be a bit more wider-lensed and start by asking ourselves what writing is and why people would do it. To me, there are four reasons for writing that come to mind:

To speak from the soul

To participate in social communication using written resources

To inform others

To endure

People have been doing all of these things for a very long time — long before Adolph Ochs was a glimmer in anybody’s eye — and Substack is of course really just a means for expressing those inclinations. Its overriding value is that it creates space for people to share, in a public forum, the kind of writing that would long have been buried in their laptops or notebooks. On this platform, for instance, I’ve been reading and enjoying Jo Paoletti’s diary — which is well-written and insightful and gives me insight into the mind of this person I’ve never met. There simply is no forum, prior to the launch of Substack (or, let’s say, of the blogosphere), that would have given me access to Jo’s diary. No newspaper would have run it — what is the news hook? — no publisher would have printed it unless Jo had gone on to be, like, a head of state or turned out to be a serial killer. A platform like Substack multiplies by some logarithmic absurdity the volume of expression in the written word. It releases founts of creativity that, for decades or centuries, were buried.

That’s the real value of Substack — and of new media as a whole. What we’re really on the cusp of is a whole different way of being — which is to be boundlessly expressive and creative, without first having to fight for access to column inches or a gatekeeper’s seal of approval. It’s what Whitman talked about when he described the “new, superb, democratic literature.” Whether we make use of that or not is really up to us. The point is that there is a new technology that makes it possible — and it’s our choice whether we want to be excited about a free-wheeling, genuinely democratic means of expression; or whether we want to just be annoyed by how many e-mails we’re getting in our inbox.

Within that larger conversation, of people trying to find expression and of writers trying to find readers, the history of newspapers and publishing houses is really just a drop in the ocean — writing accommodating itself to the Industrial Revolution. If we look at the dates of the founding of The New York Times (1851), Atlantic Monthly (1857), Harper’s (1850), The Nation (1865), The Washington Post (1877), we kind of notice a pattern. All of our ‘legacy publications’ come from a very narrow moment in time, when changes in technology allowed for the mass printing of cheap paper and for mass circulation. It was also a time of a consolidation of industrial wealth, which allowed very wealthy individuals to subsidize many of the costs of the publications usually as a nice accompaniment to their own business interests. That’s really all that ‘legacy media’ is. What it means is that publications like them have been grandfathered in over time and have a certain accumulated prestige that no rivals (apart from, say, a relative latecomer like The New Yorker) have been able to challenge. But we’re obviously in a different technological era. Being able to successfully ‘report’ on a story no longer means having the requisite connections to get a tipoff on an event, to send a designated reporter on a train or horse to the event in question, to do their reporting, to ride back to the news office at breakneck speed, to put their copy into the minimal possible number of words so as not to waste column inches, then to send everything to a print shop to be turned into paper overnight, and then dispatched — usually by legions of boys on bicycles — to the greater metropolitan area. ‘Reporting’ now often means that whoever happens to be on hand at an event captures a video of it on their phones and then opens up the field of interpretation to anybody who cares to comment. It’s simply a very different technological era, in which the whole public sphere — whether it likes it or not — has to adapt.

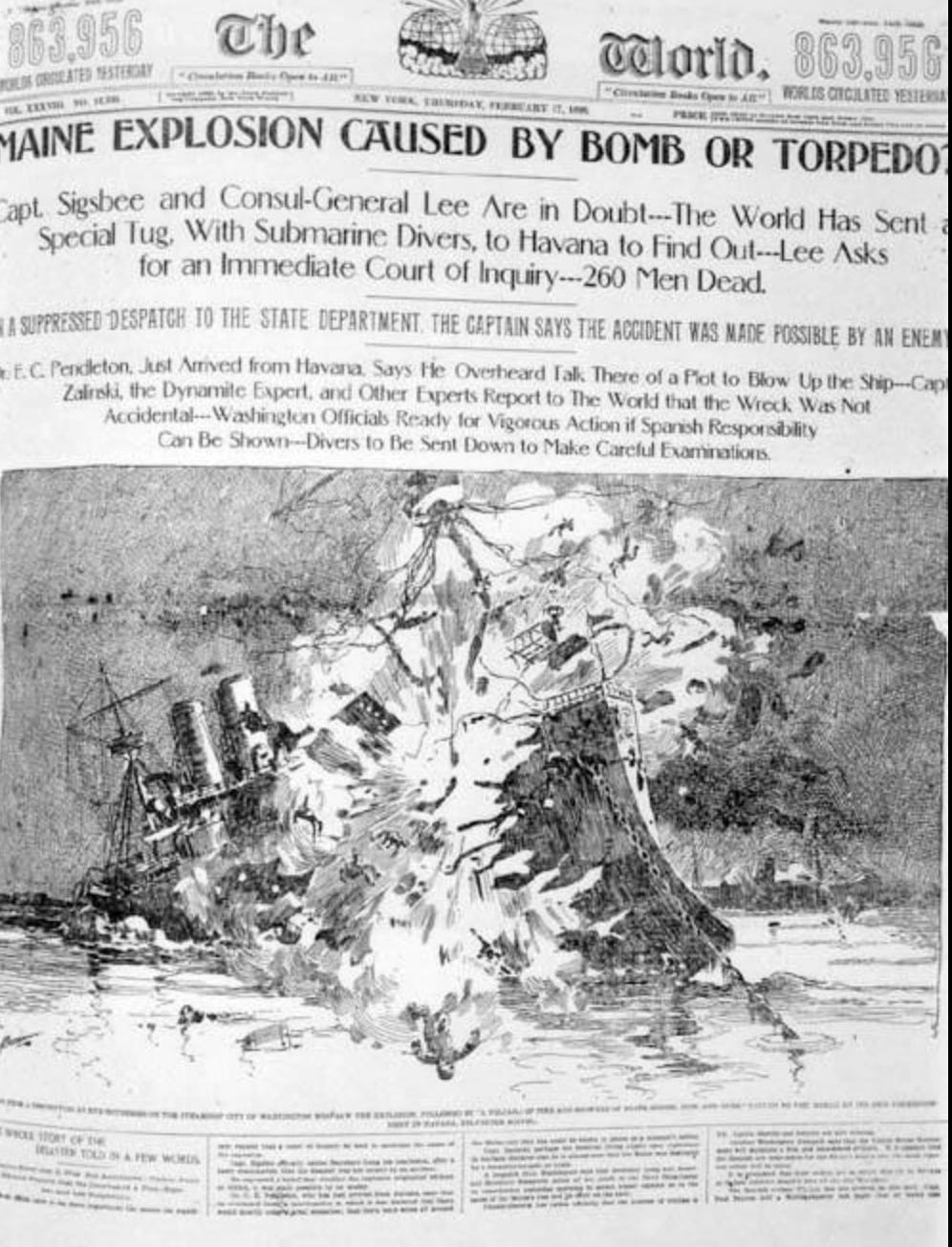

We can be as nostalgic as we want about the heyday of newspaper reporting, but let’s not forget that mass-market media cut its teeth by drumming up the Spanish-American War for the larger benefit of William Randolph Hearst’s business interests; that the media duly accepted blanket censorship throughout World War I and World War II; that the American press simply missed the Holodomor because the New York Times’ Moscow bureau chief chose to credit official reports over those of eyewitnesses and that a very similar pattern held for the Holocaust; that a CIA chief in the 1950s could routinely shout across his office, “get me the Mighty Wurlitzer,” by which he meant to call up the key figures of the media so that he could play them like an organ; that the legacy media was very slow to report on American atrocities in Vietnam and that the key reporting was done by left-wing fringe newspapers; that the same pattern repeated itself in the justification for the Iraq War, with the mainstream news outlets simply repeating the claims that the national security apparatus passed on to it.

Something very similar can be said about literary writing. The ‘Big 5’ publishing houses have their origin at roughly the same moment in time (Hachette, 1837; Macmillan, 1843; HarperCollins, 1817, Simon & Schuster, 1924; Penguin, 1935) and Rothfeld, I imagine, grew up with much the same cozy outlook I had about the publishing industry serving as an instrument of writers. But if we look closer at the careers of, let’s say, the people we would think of as the greatest writers between 1800 and 1950, a very different picture emerges. We get:

Emily Dickinson — unpublished

Walt Whitman — self-published

Edgar Allan Poe —unpublished

Jane Austen — self-published

Ezra Pound — self-published

James Joyce — published by a pornographic press

Virginia Woolf — self-published

Franz Kafka — unpublished

Marcel Proust — self-published

We could argue that all of those people did get published eventually, and recognized by the industry, but in many cases it was years after their deaths and very, very rarely does the publishing industry deserve any credit. They tended to be discovered through the hard work of friends and the word-of-mouth of writers’ circles. This is to say nothing of the situation in, for instance, the Soviet Union where the entirety of what we think of as high-end literary production (Solzhenitsyn, Bulgakov, Mandelstam, Akhmatova, Grossman) occurred outside of any kind of publishing industry.

What is at stake here really is the question of whether you want public space to be homogenous or heterogenous. If homogenous — if you like the idea of there being relatively few ‘established’ outlets, of a few books that everybody reads together — then you get a cozy atmosphere and a certain ease-of-use. But the demerits are enormous. You lose the genuine exchange of contrarian points-of-view — not just the sort of manufactured point-counterpoint of having right-of-center voices occasionally on CNN — but the real wild conversations of Seymour Hersh digging up his exposés on the natural security state, of Aaron Maté poking at the justifications for the war in Ukraine, of Alex Berenson finding all of this (compelling) data on the failings of the Covid vaccine, of Bari Weiss spotlighting so many of the holes in mainstream media coverage. You find yourself in a messy world of profoundly-competing points of view, which is as it should be: as Krishnamurti put it, “truth is a pathless land.” In the homogeneous public space, you have to ask yourself who or what is being excluded — and the answer is a lot. Were the contemporary verdicts of the publishing industry to have held, nobody would have ever heard of Dickinson, Joyce, Kafka, etc. Based on prizes, the top writer from the ‘20s would have been Booth Tarkington and of the ‘30s maybe Pearl Buck. The reason these things change is because we are — to the extent that we are — in a heterogenous public space, with people pushing back, with opinions revised, and with every perspective at some level deemed worthy of a hearing.

Taking her piece at face-value, Rothfeld is, I’m afraid, really inclined towards a homogenous public sphere. Here are a few of the more indefensible things she says:

not only do magazines and newspaper tend to contain better writing; they also tend to make for a less irritating reading experience, because they centralize different pieces in one convenient place

when i know i am writing For Publication and/or for an editor i trust, i do a better job, i have yet to bring myself to write an actual essay for substack. if you read my published work you will by now have noticed that it it is immeasurably better than the stuff i dash off on here. that’s because I find it hard to think of substack as anything other than … a blog. it’s where I go to rant. I save my considered thoughts for essays or books I intend to publish.

there are too many substacks and I would actually rather just read books, sorry

I’m sorry Becca, but this is inane. If you’re beset by too many Substacks, just unsubscribe. Do you also believe that there should be fewer newspapers because the rack of newspapers disturbs your visit to the deli? Should there be fewer books in the world because it’s hard to read them all?

What Rothfeld is writing is symptomatic of a petulant state of mind within the establishment. It’s “I can’t even…” mode. It’s the idea that public space should be as sane and frictionless as possible. Very little thought is given to modes of production and very little to questions of who is doing the inclusion/exclusion. I can understand this overwhelmed point-of-view from consumers — and this is something that Substackers have to grapple with as they fight for readers’ attention — but not from a professional critic. Part of your job is to understand the two-way traffic of communications — not just to accept the hand-me-downs from the publishing industry but to really wrestle with what deserves to be read and maybe even to champion those who are overlooked.

Rothfeld’s general attitude is more objectionable than her main point, which is that it’s hard for Substacks to compete with legacy outlets in terms of their reporting. And, yes, there is something to that. Reporting is difficult to do in terms of beat coverage or investigative reporting. But there are a few things to be said about this. One is that almost nobody in media is doing that kind of reporting. It’s a slender part of newspapers, which have become something like entertainment centers, let alone of television channels. Most outlets are given over to commentary — sometimes rewriting pieces that have been reported on by wire services and giving their spin on it — and the only real difference between that kind of commentary in a paper like The New York Times or on Substack is that the commentary in The Times has a 150-year-old imprimatur of authority on it. Beat reporting and investigative reporting do involve expenses, cultivated-relationships with sources, and (often) legal funds to protect reporters if the subject of an article tries to sue them. These are valuable public goods, and Rothfeld is right that they are difficult to replicate without owner largesse and without, effectively, the subsidy of the rest of the media organization. For these features alone, the legacy newspapers earn their survival into the digital era. But it’s not like these features are somehow the exclusive property of The New York Times or Washington Post. Anybody with the right training and perseverance can do reporting. The Free Press has shown how reportage can be a money-maker within Substack space, and I expect that many other publications will follow its lead. And, yes, many of those publications will basically mimic what legacy publications have been doing for 150 years, but they may well be able to do it better. It’s very hard to point to the Washington Post’s annual deficit of $77 million and call that a successful business model. Newer publications have an advantage by being lighter-on-their-feet, by reducing overhead for office space, print runs, etc, by taking advantage of the relative ease of obtaining certain kinds of information in the digital era.

The real point isn’t whether Substack is ‘better than’ or ‘a replacement’ for legacy media. Certainly, there’s no reason why the two can’t co-exist. But the point is that Substack is newer and in the process of its creation. Establishment media is shaped by its traditions and the fear of not living up to them — that’s what generates its quality control. Substack is shaped by … us — and by whatever we make of the platform. Rothfeld is right in a sense. If people suck on the platform, then the platform sucks. But when Rothfeld writes something like the quote above about how she can’t be bothered to put energy into her Substack post, I almost don’t even know where to begin with her. It’s like, Becca, you have 4,000 subscribers on Substack. Who are they to you? Are they less worthy of your attention than your editor? Are you trying to say that you’re only capable of having pride in your writing and your work when it’s attached to The Washington Post logo? Well, yeah, if that’s your attitude, then of course the platform isn’t going to be very good.

I’m not trying to say, with all of my cheerleading for Substack, that the platform is in some way perfect. The problems with it are, in market terms, a glut in writing which drives down the ability of any one writer to make a living from it; the shorter attention spans that come with the internet; and the hegemonic relationship of Substack corporate to individual Substacks (I happen to like the people running Substack and am on-board with pretty much all their decisions, but it is inherently an unstable relationship). But to focus on any of that is to miss the forest for the trees. The real question is why anybody would write. If the focus is on making money, then, I’m sorry, but literally almost any other activity is a better choice for you. If the reason you write, though, is to express yourself and to reach others — as yourself, not through some Wizard of Ozian stamp of authority — then what you care about is having the opportunity to be free. Substack gives you that. If that’s not what you care about, then it might be time to rethink your priorities.

Emily Dickinson — unpublished [12 poems published in her lifetime, close relationship with Atlantic editor Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who oversaw her first posthumous publishing]

Walt Whitman — self-published [the first two, tiny runs of Leaves of Grass, which were afterwards brought out by established publishers and expanded to include new poems, nearly all of which first appeared in national magazines and newspapers]

Edgar Allan Poe —unpublished [this is the strangest one, as Poe mainly worked as a magazine editor and The Raven was a print sensation in 1845 (which Poe published several times anonymously so that he could keep selling it to other newspapers)]

Jane Austen — self-published [works published by Thomas Egerton, an established bookshop and publisher albeit with her brother assuming the costs of printing]

Ezra Pound — self-published [are you referring to Egoist Press? Pound never had the money to self-publish but was an irrepressible lover and participant in Little Magazine culture. Perhaps consider that one of his closest friends was the publisher of the still-significant New Directions press, which keeps much of his work in print today]

James Joyce — published by a pornographic press [is this your description of B. W. Huebsch, which became Viking Press? My guess is that you’re referring to Samuel Roth, who was a significant publisher of other modernists, but more to the point, his Ulysses was a pirated third edition that had no participation from Joyce]

Virginia Woolf — self-published [first novel published with Duckworth under the aegis of Jonathan Cape, her reputation was established by her frequent contributions to the Times Literary Supplement]

Franz Kafka — unpublished [published two collections of his shortstories with Kurt Wolff, who would eventually establish Pantheon Books in New York after fleeing the Holocaust]

Marcel Proust — self-published [Proust covered costs but Du côté was published by Grasset and all subsequent volumes with Gallimard, France’s largest and most respected publisher at the time]

I went back and read the exchange between Dematagoda and Rothfeld…I think I mostly agree with him to the extent that they are even talking about the same thing but I have to say that her reaction, if not exactly admirable, is a pretty predictable response to some guy she’s never heard of (who happens to have a literature Ph.D, but who’s counting credentials?) showing up out of the blue and calling her a delusional tool of ‘the oligarchy.’

He also says the following: “I’m in favor of a free press and real journalists who adhere to objective journalistic standards, not propagandists in thrall to power politics simply because it might cohere with their own worldviews.” Then he completely evades the question of how, exactly, this kind of reporting can/should be done so that he can keep going on about the inherently corrupt nature of the establishment press and expressing his personal contempt for Rothfeld specifically. I don’t think this is really productive. Sure, there are major structural problems with the legacy media, and sure, it is annoying when people attached to that legacy media refuse to take those problems seriously. But if you focus on this you are avoiding what seem to me to be the harder and more important questions, like what ‘objective journalistic standards’ actually are or how they could be maintained in the highly decentralized future many people are predicting for journalism. Lastly, I want to say that the ‘I’m from Britain, so I don’t really care, but,’ stuff is extremely annoying and kind of makes me want to side with her on purely patriotic grounds.