Philip is supposed to be some kind of drug dealer. And my idea is that that spares me from having to hire any security for our shoot with him in San Francisco – he knows the streets and he’ll protect us. But that’s not flying with the DPs. I’m a field producer on documentaries and I’m used to DPs hanging out of car windows to get shots of tires; of DPs taking gigs for a month in Africa starting days before the birth of their kid. So I’m having trouble believing that I can’t get a DP from California to shoot in San Francisco, but they’re all adamant about it. And in the end the compromise isn’t security per se but to hire a PA who knows Muay Thai. And then we fly up from L.A. to San Francisco and deal with rental cars and gear and just stand on a street corner in the Tenderloin waiting for Philip to pull up while the Muay Thai-trained PA stands with legs wide apart and knees bent.

The Tenderloin really is like nothing I’ve encountered – it’s like my vestigial memory of New York in the ‘80s. The scam apparently is for two guys to drive a car slowly down a street, one driving, the other hanging out the back window with a baseball bat, and to smash the window of each car on the street and to dive in and take the valuables. And some insane San Francisco ordinance prohibits cops from giving any kind of chase, so the parked cars are lined with begging placards insisting that there really is nothing at all in the vehicle. And Philip is of course not where he’s supposed to be and not picking up the phone – “he’s not good with his phone,” my contact with him has warned me. The Muay Thai PA claims that the thing to look out for is ‘spotters’ wandering by, checking out the camera gear, and then rounding up their people. And it really would be an astonishing new low for a shoot to never even meet our subject, just spend the day marooned and maybe mugged in the Tenderloin.

My contact tells me that he’s “just getting high dude,” and then an hour after he’s supposed to meet us, Philip wanders up. He’s definitely not a drug dealer. He’s a very sweet, small, bearded guy, with hat, backpack, jeans jacket with a patch of a UFO. He’s a grower, works when he works on a cannabis farm in Grass Valley. And then when he has money comes into the city, squats with a friend, and just spends his time smoking heroin off tinfoil.

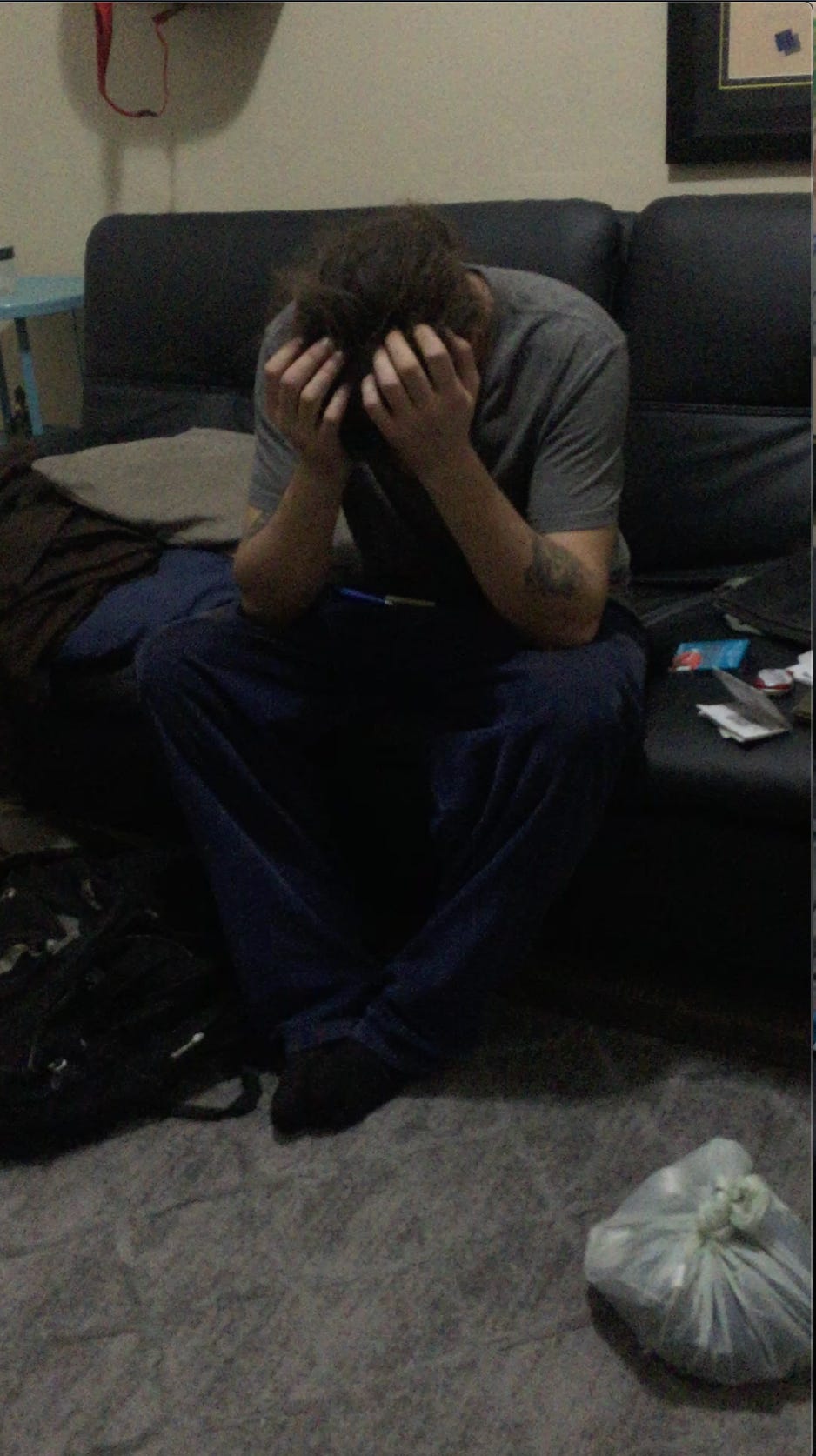

It really is a relief to have keys and to step into an apartment. And then there’s sort of nothing to do once we’re there. We do interviews with Philip, who is very soft-spoken, very worn-down. He has a few calls to make – to the intake people at the ibogaine clinic, which is his destination this week – and we duly film those. Every so often he wanders to the bathroom for a long time and the DP, who’s wearing headphones connected to Philip’s mic, reports that he’s smoking. We wander around, we get food, we do an interview in a park. His story is pretty straightforward – it feels like par for the course for a whole generation. He grew up in Vermont, had a nice family actually – none of the clichés about childhood trauma – still has a good relationship with them, which is a small miracle. He started taking percocets when he was 14, got in a bad car crash when he was 17 and the doctor prescribed oxycontin. And that was it – straight to the bottom for him. From oxy he moved onto heroin, got clean when he was snowboarding in Utah, managed to stay clean for a few years, but “dabbled,” and then in 2013 went down the rabbithole, as he put it, and hasn’t come out since then. “This is not where I thought I would be in my 30s,” he says, “that’s for sure. I just don’t have basic things in life that I should have by this point.”

There was a girlfriend somewhere along the line, but it fell apart. Pot has been a constant, and, he says, a good thing. But then, once he realized that San Francisco was basically “an open air drug market, that was the end of me.” He’d usually have about $100 in his pocket at any one time and then he’d burn his way through it in the Tenderloin. The heroin wasn’t for highs at this point, it was just “a maintenance.” After a few hours without he’d start to get twitchy and shaky, feel “not great” in his own skin, it brought out anxiety – which, he says, was really the underlying issue all along – and the heroin made him feel “right with himself.” It was cozy, peaceful, he says. At some point, hearing him talk for awhile, seeing that he’s lucid, competent, can work, can drive a car, I start to wonder if I’m maybe misunderstanding, if he isn’t one of these Carl Hart-type high-functioning addicts. I ask him what heroin is to him and he chuckles at that and says, “It’s definitely a dark entity in my life,” and the tone of his voice puts to bed, for me, the whole Carl Hart hypothesis. “It’s like this all day every day,” he says. “It’s like not a good way to exist.”

And the ibogaine treatment – the reason we’re here – isn’t necessarily some sporting cliché, last chance or anything like that. But Philip has tried everything else, keeps going in the opposite direction. “I need to address this before, you know, I wither away essentially,” he says. “You don’t hear about many aging heroin addicts, that’s for damn sure.” He saw a note on a bulletin board just saying ‘Ibogaine’ and felt an overpowering resonance. “I researched it and found out it was a psychedelic that helps you get over your dope sickness and that was mind-blowing to me,” he says. And then a conversation with somebody who actually was a drug dealer (hence my initial misunderstanding) who’d gotten clean with it; and money borrowed from a friend who couldn’t really afford it to buy a ticket and go to Mexico for a week-long treatment. And as much as I’m trying to get soundbites out of him the overriding feeling is of exhaustion and relief – sooner or later, something has to give.

The Muay Thai PA successfully stares down a pair of spotters. We finish the interview, wend past a guy splayed fully out on the park steps. We’re not really sure what to film so we just roam around the wasteland of the Tenderloin. People are shooting needles in the open. People have enormous boils from skin infections; Philip, as tour guide, explains that there’s a strain used to cut coke that a lot of people are allergic to, they snort it anyway, but the allergy makes the skin puff up like elephantiasis. We go to a Goodwill – Philip wants to get some things for his trip – and a guy outside wearing a security guard’s uniform is ripping off his belt and spraying himself with Windex. Our first thought is that that’s kind of funny that that’s who Goodwill hired for its security, but then I realize that it’s just a guy who happens to be wearing a security guard’s uniform ripping off his belt and spraying himself with Windex. As we wander around, we start to notice that Philip has a habit of picking wrappers off the street and throwing them away in the nearest trash can. We stop off at a Burger King – Philip just wants to use the bathroom so he can smoke heroin there. To use the bathroom you have to buy something and Philip gets a $4 sandwich. When we’re back in the street he wanders ahead of us, finds somebody resting on the seat of a bus station, leaves the sandwich next to him.

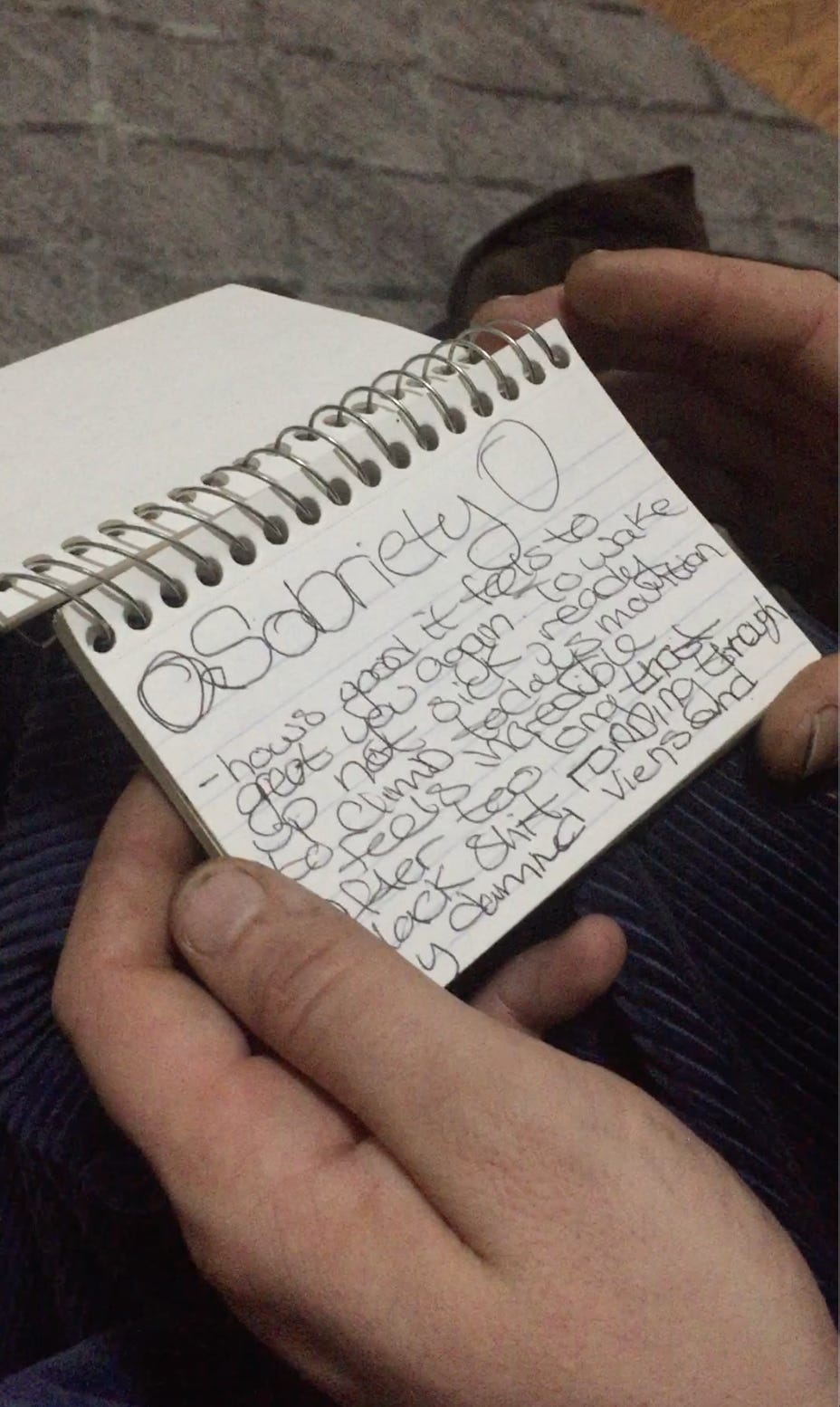

And – what else? Another interview, to cover material he’s already talked about. He shows us his notebook – “journaling notes: dreams and such.” There are notes about going back to school, “mostly to-do lists,” he says, his wry chuckle, “that are unchecked.” There’s a giant note taking about a half-page, as part of a to-do list, saying “SOBRIETY” and underneath, “How good it feels to be you again.” About thirty times we follow him out to the street and film him smoking a cigarette. At some point he gets tired of visiting the bathroom and he graces us with a shot that, honestly, is very important to us – “I figured you’d want that at some point,” he says considerately – and takes out tin foil with a sticky black tar substance on it, lights it from underneath, and something does change, he gets a little heavy for a few minutes, kind of nods off, something relaxes in his features, but it’s subtle, he’s pretty much chatting the whole time. The smell of it is sickly sweet – after a while, I have to excuse myself, go to a coffee shop. I’m not sure what I’m afraid of exactly – I don’t think I’ll actually snatch it from him or anything – but there’s some odd feeling just from being in the same room with it, like whatever hold it exerts is more powerful than anybody’s willpower.

At dinner the crew agrees that Philip is just from another world. “It’s always like that,” says the DP, “it’s like they’re always made of just thinner skin, they need some cushion against reality.” I’ve kind of been on the ‘opioids beat’ for a bit – finished a documentary just before that about a treatment center in Illinois. And the surprise had been how much I loved interviewing the addicts – I’d expected people to be guarded, evasive; active addicts were supposed to be master manipulators, but by the time people were willing to give interviews about it there was no filter. A sentence might start “Right around the time when I hung myself and Chad cut me down…” and then finish in a completely different place – some present-day frustration with Chad for instance – like the opening really was just to supply context. What had stayed with me most was an interview I saw with an active addict, a 21-year-old girl who would almost certainly be dead within a year or two. The interview was a bunch of do-goody questions, about treatment and rehab, and she’d answered like she was reading from a psalter, and then the interviewer ran out of ideas and said, “So what’s heroin like?” and she kind of bolted upright and her eyes shone and she said, “It’s like you’re a puppet and God is pulling the strings.” But even among those, Philip seemed to be particularly Christlike, heavy and drugged but also elfin and fairylike, eyes dark and bright, from another world. “The problem,” says the DP, after a few drinks, “is that he’s not really a Philip – what went wrong is that he was given the wrong name.”

There’s drama about his passport. In the morning, or midday, when we meet him, he says, “Do you want the good news or the bad news?” I ask for both. The good news turns out to be completely inconsequential. The bad news is that he hasn’t been able to get his passport renewed. He’d made some mistake – the usual problem, he says, of leaving everything to the last minute. He’s supposed to get on a flight that evening, and we have to let the flight go (at his destination they’re very understanding of this), make an appointment, go to the federal building – which happens to be on the same block as where Philip buys his drugs. Philip makes it through the medical detector with magic mushrooms in his pocket. The woman at the passport counter doesn’t want to touch his passport, which is like molding, grabs it with Kleenex, aggressively moisturizes her hands afterwards.

There’s time to kill. He spends it smoking heroin. There’s a terrifying moment when he says, “Wait here, ok?” and goes to the car to get socks – and then is gone for about 40 minutes and I’m sure that he’s taken off, that he’s high-tailing it to Grass Valley. Doesn’t want any part of a documentary, doesn’t want any part of getting clean.

And by the afternoon the next day, incredibly enough, the passport’s ready. I try to leave for the airport about six hours early. Philip disappears for about the tenth time. I go for a trepidatious walk, find him smoking around the corner. “I just needed a break from filming,” he says. And then we have the world’s most harrowing trip to the airport. I think I should drive, since he’s high. But as I’m going to the driver’s seat, he says, you have to keep the RPM at such-and-such and that decides us. This is his car – he knows it. “It looks like you just came from Burning Man,” says the DP, which is a really stupid thing to say – it looks like a guy living in his car, the car completely run-down. He takes a hit of heroin – the DP memorializing it as maybe the last hit. He jumps it to start and then has to keep it moving so it doesn’t run down. Unfortunately, that’s not so easy to do at rush hour in San Francisco, and every time we hit a stop, which is frequent, he turns off the headlights to save battery and we hear the motor sputtering down. We narrate every single move of the trip, every time we move a little closer to the light, every time a car passes a light. The gas tank is of course very close to empty and we have to deal with that as well, navigating to the station and then back into the same traffic we hit before. The DP wants to film every moment – it’s his training – and I have to tell him to hold off and focus on just getting us there. The car’s left in long-term parking. We get the shot of him printing out his ticket. There’s a perilous moment, the DP and I waiting in the terminal passing off footage, Philip pacing around outside with a cigarette and if he’s going to run off he could still do it, and then through airport security and I have a drink at a bar and out of sheer relief (for Philip’s sake, for the sake of the documentary) send a selfie of myself with a beer to just about everybody I know.

***

And Clear Sky – the ibogaine recovery clinic in Cancún – is just a different world. Philip takes a valium on the plane and he’s pretty out of it, seems very ill-at-ease in the Mexican sun. Clear Sky is a very low-key place, more a house than a clinic. The staff are all in uniforms, clean, nice. Two doctors, three or four nurses, kitchen crew. There are about four patients in the place at any given time, they’re in their own sleepwalking kind of state. The name comes from one of the earliest patients. He had gone through his treatment and went outside – a strip with beachfront, jetty for diving – and looked up and said, “Oh a clear sky.” And that seemed to encapsulate the experience of the place. The addicts show up, they’re completely tunneled in to their phones, they’re thinking about fixes, they’re having ongoing fights with everybody in their lives, and then the ibogaine takes effect, and suddenly the non-heroin existence comes into focus.

This is the world of offshore medicine, which everybody is biased against; and not only offshore but non-FDA-approved, ‘voodoo medicine,’ the bark of an African shrub that’s supposed to have this outlandish ability to cure heroin addiction. It’s actually a Schedule I banned substance in the U.S. – right alongside heroin – and it’s also like, come on, were we born yesterday. Which is clearly how the crew feels, although they’re trying to be open-minded, and how I would feel if I hadn’t already had my worldview turned upside-down by iboga – in its ‘spiritual’ application – and if the numbers behind ibogaine weren’t so dazzling. Everything is professional but at Clear Sky the vibe is so laidback that it’s hard to shake the feeling that they rented an Airbnb and threw on doctors’ uniforms. Dr. Sola, the mild-mannered chief doctor, has twenty years ER experience but also used to be like a gangster’s private doctor. Dr. Felipé, the second doctor, was the on-call doctor for a Cancún teen tour. He was expected to stand by for the inevitable point in the evening when the teens started to develop alcohol poisoning.

Philip goes through intake, he has various monitors strapped to his chest. He’s asked what he’s here for, and he says, “Uh heroin,” and narrows his eyes in the way he does when something really pains him. And then – not much to talk about. He’s sent to a room to rest. There are three other patients, a woman arguing angrily into her cell phone, a sweet smiling kid from Massachusetts who got clean here once and then relapsed and has come back again, a very tall drug dealer named Rob, always in a hoodie. Patrick, the clinic’s owner, turns up. He’s a real character, conscious of being a character, vaping, in a bandana, round glasses that make him look like he was the original founder of the internet. Which he sort of was. His story is that he came from a wealthy family, Pentagon contracts. He was a teenage prodigy computer hacker in the ‘80s. As part of the nocturnal world he was in – Greenwich Village, anarchism – he in due course became hooked on heroin. And that just subsumed him for a long, long time – led to arrests, the collapse of his company. Deborah, his mentor, the woman who got him clean, remembers him coming into her clinic – part of a study she was conducting in St. Kitts in the ‘90s – and thinking that he was “foul: he smelled and he cursed,” and she tried to send him home and he spat on the floor, stormed off, thought about it, knocked on the door of her office exactly like a penitent student and asked for one more chance. It was a horrifying, devastating trip. “I died over and over again, went to hell over and over again,” he says. It was by far and away the most difficult thing he’d ever done, but somehow, by the time he came out of it, he was different. “I had a huge habit and it was like it got lost in inner space,” he says. But he knew that if he went back to New York he would relapse so asked if he could hang out in St. Kitts and Deborah made him her research assistant. “I was the lab rat that could,” he says several times – he’s become such a character in his own life, he has a tendency to repeat his sentences. And then he really did effect an incredible transformation, has a family, a good business, wrote a novel about his whole wild ride. At some point, he says, “I did something from which there was no going back from,” went on television, confessed himself to be a heroin addict, showed the track marks on his arms, talked about his unconventional path to getting clean. His family was conservative; that was the end of his relationship with them. But the stigma around heroin was a real problem and he felt that he had to stand up for addicts, show that somebody ‘normal,’ or at least successful, could be an addict, that it was possible to get clean. And then he went deeply into psychedelics, felt, first of all, that the U.S.’ drug policy was a complete travesty, that what was promoted was the “bad joke” of the recovery industry, with a “success rate of about 10% - and that’s being very generous, it’s more like 4-6%,” and then there were all these terrific treatments, ibogaine most of all but these other plants and psychedelics as well that were fringe, completely buried.

It was a very easy decision for Patrick to go into business with ibogaine. Deborah, his mentor, had credentials as a serious research scientist – ironically, she’d gotten into ibogaine in an unsuccessful attempt to debunk what she saw as a counter-culture myth – and felt she had to keep some distance from the clinics. She encouraged Patrick to open Clear Sky, which wasn’t the first offshore ibogaine clinic but probably the most successful – 4,000 patients over 20 years, no significant adverse results, a recovery rate of 95%. Which is a hard number to grasp but there it is – not a double-blind FDA-approved trial but real clinical data stretching back twenty years. They’ve wanted to do follow-up, did a half-hearted study but didn’t have the manpower to track patients down six months or a year after they’d left. The estimate was that after a year or so the recovery rate drops to about 40%. But that’s without the infrastructure for any kind of follow-up or integration – with patients usually going straight back to the environment where they’d gotten addicted in the first place – and eight or ten times more successful (as well as cheaper) than traditional recovery.

Patrick has been doing this so long and is so chill about it that it’s sometimes hard to kind of get him to remember the enormity of it. His interest had moved on from psychedelics to transhumanism. “I’m always ten years ahead of every trend,” he says. He’s on this complex cocktail of substances – HGH, etc. “Stacking them,” he says. His claim is that for every one year he ages he goes 2.5 in the other direction. These are the kinds of things that make you a bit skeptical of Patrick; and those gains seem to be offset by vaping, by constantly chugging coffee – two Starbucks ventes at dinner. There’s some idle speculation in the crew that he may be back on something stronger, but everybody’s just being mischievous. Really, he’s built something amazing; the number of patients, the variety of patients (among many others, Navy SEALs, Delta Force veterans addressing their PTSD). To get him to demonstrate his achievement for the camera, we make him take out the guestbook and he reads through it – it seems like the first time he’s read it in awhile, like he’s reencountering some old friends – and it really is like nothing I’ve heard before. “Ibogaine saved my life.” “I was praying for something, I didn’t think I would get it.” “Clear Sky was a last resort, a long shot, but I woke up from treatment as if reborn, alive with senses I hadn’t felt in years.” “Take this moment, breathe the air, hug the staff, feel the tears coursing down your cheek. You have waited so long for this – you didn’t think this would ever happen. Enjoy!” And on and on, to the point where it became monotonous, tiresome to read.

Philip is going through a detox period; he’s on short-acting opiates to mitigate the withdrawal (this being necessary, really, because heroin is intercut with so many substances now that it’s impossible to know what’s in anybody’s system). He spends almost the whole day in his room. On arrival there’s an intense search of his possessions, although stopping at a cavity search. “We will never do that,” says Patrick – although, to be honest, that’s taking a significant risk; addicts are geniuses, especially at this stage of the game, in sneaking in drugs. Patrick has the story of the patient who slipped out of her bedroom window at night, hailed down a car, got the driver to take her from pharmacy to pharmacy, using each pharmacy that had rejected her as a kind of referral to the next pharmacy, finally tracked down some sort of oxycontin, drove back to Clear Sky, told the driver to wait a moment, and then crawled back through the window and into bed – and would have gotten away with the whole thing except that the driver knocked down the door at two in the morning demanding to be paid and managed eventually to be believed despite the patient’s utterly disarming protestations of innocence.

This stuff is not really cute. The problem with ibogaine – and one of several reasons (actually, probably, the least important reason) why nobody in the medical establishment will touch it – is that it is occasionally fatal. People who have been working with ibogaine for decades are convinced that they have narrowed the risk of fatality down to two causes, a rare and readily detectable heart condition and active interference from other substances. The protocol is to wean people off their SSRIs and MAOIs before taking ibogaine or its progenitor iboga. For spiritual seekers, that often means an agonizing decision to pause anti-depressants for the sake of a more radical approach. But, for the addicts, it’s literally life-and-death; and as much as ibogaine centers try to screen for it with searches, intake forms, it is very hard to stop an active addict from taking what they’ll think of as one farewell hit before getting clean. Just about everybody who’s worked with ibogaine for any length of time has had a patient die while under their care. This is of course also true for probably the entire medical profession, but the responsibility weighs more heavily on people who are not buttressed by the medical establishment, who have decided to risk everything on an ‘unproven,’ ‘dangerous’ treatment and to do so with active addicts. Most depictions of ibogaine treatments tend for tabloidish reasons to focus on an either/or vision of the outcome. “Documentary maker may film his own death” is a typical headline – part of a sweet but deranged documentary depicting a treatment. That idea is unfortunate and has compromised any attempt to have a serious conversation about the out-of-this-world efficacy of ibogaine, but the risk is real and all ibogaine providers have had, one way or another, to make their peace with it. Clear Sky, actually, is one of the few that’s been lucky enough to not have a fatality, but death is always present when dealing with addicts. Patrick, chatting with the crew at our hotel, looks to an upper-floor window and says in his dry way, “That was the end of Matthew Mellon.” The story is that he’d been working for awhile with Matthew, a Mellon family heir. Matthew had a vicious oxycontin habit, had gotten clean at Clear Sky – “I had a spiritual crossing with ibogaine,” he wrote on Instagram and offered to pay for anybody seeking treatment – relapsed, came back to Cancún for another treatment, delayed his intake, died at the hotel of an overdose. It was a major news story – and, if you google Clear Sky, that’s what comes up. The streak of 4,000 to zero for treating patients doesn’t come through; Clear Sky is implicated by association.

While Philip is going through detox, we make do with what we can. We do an interview with Rob, the tall drug dealer. Rob is almost incoherent when we see him at meals, his black hoodie pulled tightly over him. The assumption of the crew – crews always jump to conclusions – is that his brain has been scrambled by all the drugs (and hopefully not by the ibogaine). Also, unnervingly, he has a giant tattoo of the Grim Reaper with a caption saying ‘Game Over.’ We do an interview, for form’s sake, and because we’re told by the staff that he’s had a very successful treatment, and he turns out to be absurdly reflective and articulate. Rattles off his whole life in the unfiltered way that I’ve gotten used to from addicts. He describes his entrepreneurial spirit – he grew up in all kinds of luxury in suburban Maryland but just had an urge to make money, which as a teenager meant dealing drugs – and he became the kingpin of the Montgomery County School District. He was a millionaire by his early 20s, but he suffered from withering depression, had had a gun pulled on him during a deal and was traumatized by that, had a heroin problem and a gambling problem, lost pretty much all the money, was busted and spent four years in a federal prison – he made a big point of emphasizing that it was federal prison. He talked about prison, the race riots, the whites and Hispanics against the blacks, the alliances he tried to forge, the tattoos he got from this guy who was a renowned prison tattoo artist – he felt the Grim Reaper tattoo was just self-explanatory, that’s the way it is, what we all need to be reminded of – the time he was in solitary confinement and went deep inside of himself, really got to know himself. Then released, founded a pill mill prescribing oxy – that’s the only thing he regrets, he says, the advantage he took of other addicts, but he couldn’t resist the opportunity to fuck with the government; this was the one time he was dealing drugs completely legally and he was causing by far and away the most harm. His parole officer didn’t like it, but for different reasons – didn’t like that he was running a business; wanted him to work at Stop & Shop. He just couldn’t stop himself from making money. As cannabis was becoming legal, he became a cannabis entrepreneur, made a ton of money again. But there was the gambling problem, which was exacerbated by heroin; on heroin he would lose his judgment. So he found out about ibogaine, came down to Mexico, had a very smooth treatment, no cravings. He was ebullient. “If I was killing it high I’m going it kill it sober,” he says. He’d been very worried that certain painful memories were going to flash by for him – the gun to his head, the time he was pistol-whipped – but it was, he says, “lovely, just a lot of colors and dragons and for a while I was talking to my higher self and it was very laidback and mellow and chill and very comfortable – I’ve done every kind of detox program you can think of and this was the most uplifting, spiritually, mentally, physically, and I can put my hand on that to God.”

The last day he’s there he’s pacing around panther-like along the beachfront, doing business, working out the logistics to fly his girlfriend, or one of them, down to Cancún so he can really celebrate his sobriety. Well, who knows how long that will last; and it does seem to put to bed a notion I’d had that everybody who does iboga or ibogaine comes out on the other side intent on transforming themselves in toto. But, on the other hand, I’m probably being a prude. Rob is incredibly sharp, seems to know himself – really know himself. The staff all feel like he’s a model patient.

After a couple of days of detox Philip is ready for his first dose. It’s done at night – ibogaine and iboga are always at night. He’s in what looks to be just a normal doctor’s office. Music is set up for him; he’s given eyeshades to wear. Dr. Sola the chief doctor is a very square kind of guy, has never taken ibogaine himself in all the time he’s worked here, talks always about protocols and physiology, but even he can’t resist a certain sense of ceremony. He gives a speech saying, “In Africa, it is an initiation. It is where a boy becomes a man. It is climbing a mountain inside yourself. It will be difficult but at the end you get to the top of the mountain. You’re in a better place. Have a safe journey.” And then Philip takes the capsules and puts down his eyeshades and slides on his headphones – a playlist that’s been carefully curated over years, some Enya, mellow Mexican music as inputted by the nursing staff, but predominantly iboga music from Gabon. And then everybody files out, leaving behind a camera and a night nurse – it’s very much the feeling of being in an air traffic control tower, sending off a night flight, the lone nurse monitoring the EKG, staring at the controls.

And because we have a camera, the reality TV bug gets into us a little bit, we spend the next days building drama out of every micro-progression in his journey. He has achy, restless legs. When he gets up to go to the bathroom, he has ataxia – the same thing you get when you’re very drunk and stagger around – and a nurse has to help him. The DP is careful to film every step. We get the chief nurse saying sorrowfully, “He’s uh he’s not doing that well.” We make sure to have lots of close-ups of nurses studying the read-outs of his EKG and his vitals. But, really, everything that’s happening is completely internal. I know from having done iboga before a bit about what Philip’s going through – flashing images, like stills in a waking dream, and the uncanny ability that the ibogaine or iboga has to dredge up the sides of yourself that you’re absolutely most terrified of seeing. The first time I did iboga, during a ‘spiritual’ ceremony, the guy who was ‘on the floor’ next to me was an alcoholic in recovery. The ceremony’s leader encouraged him to try to figure out the origin of his alcoholism, and my companion said, in his attractive drawl, he was a very handsome, successful actor, “You know, I never thought about it before.” And then closed his eyes and when he spoke again described an image of being on a beach and looking out at sea and seeing a tidal wave forming, but pink, and then the wave cresting up over the horizon and crashing over him – which sent him into a round of vomiting into the slop bucket in front of him. But the sense is – and this also was what Patrick was describing – that the iboga knows, that the iboga is like the best friend you’ve ever had (which has also been my experience), the tough love friend – a ‘stern father’ is a very common expression in iboga world – who sees all the bullshit you’re hiding from and puts it right in your face and somehow, as in the way of all spiritual wisdom, the looking unflinchingly at your own patterns, your own ‘shadow,’ is enough to help you work through it. In Bwiti ceremonies – a Central African spiritual practice for which iboga is the centerpiece – it’s traditional at the right moment to present an initiate with a mirror, with the idea that they should see themself as if for the first time. And if Philip isn’t communicating much, just a thumbs-up from time to time, some muttered monosyllable – that’s what I tend to assume is happening, image after image popping up, some of them deeply personal, some of them fantastical, some like intricately posed riddles, but all pointing, with unnerving accuracy, towards a psychological core.

Passing the time, there’s a nice, healthy debate between doctors and nurses about how exactly the ibogaine functions. Dr. Sola, man of science, says that the whole ibogaine process can work perfectly well even if patients are unconscious – people sometimes want to be spared the ‘visuals’ and the whole psychedelic trip and ask to be knocked out with a valium – and Sola says that in his experience the results are exactly the same. Q.E.D. – ibogaine is essentially physiological and the ‘light show’ that can be so meaningful to patients basically a distraction. Marcela, the very brisk, businesslike chief nurse, hears Dr. Sola say this and doesn’t comment, but then, alone, she says, actually, that she completely disagrees. She’s been here just as long as Dr. Sola, seen just as many patients, she’s coming just as much from a medical background as he is – nothing woo-woo – but she is convinced that what happens during a trip cannot be completely explained at the level of chemistry or physiology. “I spend the whole time with the patients,” she says, “I think what happens is spirit.”

Philip’s trip takes a little longer than usual – there are a couple of different doses, the Clear Sky staff staggers the dosage over more days than usual. He complains about aches, he doesn’t talk much, the documentary suffers, and then on the fourth morning after taking the ibogaine he wakes up like a completely different person. He’s shining, articulate. He joins in the yoga class that’s held daily in the back patio. He asks to go for a swim and wanders out to the pier, somebody keeping him company just because he’s still a patient, jumps in the ocean – his first swim in years. He asks for a haircut – the first in ten years, he estimates – and it takes a very long time, the barber working hard to untangle all his matted hair. He’s still a little withholding with the soundbites. He says underwhelming things like, “This is the easiest detox I’ve ever had” or “I can’t believe this is illegal.” And then things that are a bit more intriguing, hearing at some point in the trip a voice deep inside himself chanting “Iboga iboga,” having some flickering visions to do with Africa, and a quiet voice like a mantra telling him over and over again that it’s all going to be alright. “It’s work for sure,” he says. “Day two was, you know, questionable. But day three started to get a little better with some discomfort. And then day four I woke up feeling pretty damn good.” He says he just doesn’t have any cravings. He lies around in his room, in the time mandated for rest, and he watches snowboarding on TV and thinks about how that’s what he wants – just wants to make sure he doesn’t go back to the Tenderloin, wants to live somewhere out in nature, make some money, start to put a life together.

At checkout he’s given his backpack and the tattered jacket with the UFO logo on it. It’s not his style to write in the guest book. He stops off at the long-term parking in SFO, leaves the keys in his broken-down car, leaves a note on the windshield, apologizes for leaving it there but invites anybody who can make use of the car to have it. He and Patrick have chatted and Patrick connects him with a Buddhist monastery in Thailand that was instrumental in his own recovery. That’s more money he has to borrow, another plane ticket, but Philip has always inspired loyalty in his friends. Kevin, who paid for the ticket to Cancún, also springs for Thailand. The monastery so happens to be right in the Golden Triangle – the world’s most potent opium is harvested right up the street – but Philip spends a whole month there meditating, treating it like a halfway house. He goes back to Grass Valley, farms, starts a relationship with a girl. It sounds like it’s not easy – we text from time to time – he says he’s “working like a madman to stay on top of finances.” The last time I talk to him he says he’s still clean. And that’s all – a very quiet guy, closed guy, it was very rare to see him smile; smart, witty, kind, clearly having trouble adjusting to earth’s orbit. He was so matter-of-fact, so low-key – and everybody at Clear Sky was the same way – that it was easy to miss the magnitude of what had happened, I felt like I got it only because I’d spent the couple of days in the Tenderloin with him. As somebody else put it – a veteran ER doctor, Jeff Kamlet, describing the first time he saw an ibogaine treatment – “I saw something,” he said, “that I believe was a miracle.” And that’s right – it’s not a word that it’s occurred to me to use at any other point in my life, but I saw Philip in the Tenderloin, I saw him leave Clear Sky, and I talked to him clean and sober months later. Miracle is the only word that fits.

Some identifying details have been changed for this essay. There’s lots more to be said about iboga/ibogaine. The conceit here is to write from a very narrow vantage-point - a few days spent with ‘Philip’ at a critical stage of his recovery.

Lot to process here. Keep it up.

I still have ashes in my mouth (heart,eyes) from the mid-afternoon call dec 27th 2018. I’m in PDX. Mindy calls me from the Philly Coroners office. This is where they have taken her son Nick. I didn’t know she was calling from there,obviously. But now that I know that’s the picture I conjure when I think of this which is often. What did I know ? I Knew she went up to Philly to see if she could find him. Find Nick. And I guess she did.

When I started reading about the Opioid epidemic @2004 it was as a disconcerted observer of the “Current Affairs” “stack of New Yorkers on the bedside” variety. Accustomed to the genial warnings of doom that emanated from my literary grazings. Like someone accustomed to flood warnings coming it nothing.

suddenly, in seconds it seemed, the water was lapping at the back stair. Since Nick there have so many many many others. I remember how it’s like AIDS when it flooding the lower east side - all us writers and creatives living there cheap frenetically - then, all this dying. There was a fair amount of heroin then too but we didn’t have specific feelings about that. It just was part of the general vibe of decay we felt so present to, coming out in different ways among us. Some better. Some worse. We green. the first volunteers to the newest war.

I loved this piece so much because there have been a lot of hopeless tears cried over this and since I’ve heard them live and raw I can report even if you are not directly involved it guts you forever. This problem needs hope and this seems promising to incredible. Even if it’s half as good as the claims here that’s stunning. I love your writing